By Anouar Majid, Tingis Redux, February 22nd

A few months ago, I immersed myself in a kind of reading that I wish was available to me and my teachers when I was in high school in Tangier (Morocco) studying philosophy and Islamic Studies. It is the kind of slow—very slow—reading that keeps you constantly challenged and fully awake. It is archeological and historical work informed by a knowledge so vast that a reader must struggle to keep track of all sorts of cultures, languages, dates, and names. Only scholarship of this scope, though, can aim at the heart of gigantic myths—myths so powerful and persistent that centuries of generations have taken them for reality and billions continue to believe in their truth.

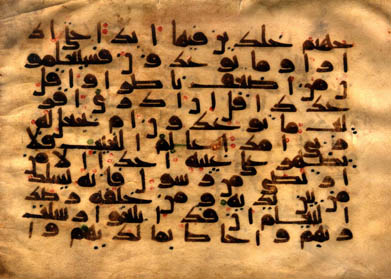

I decided to devote some time to the work of Professor Patricia Crone because her name kept appearing with increasing frequency in the literature I had been reading in the last few years, whether by scholars who share her general view or not. I thought it was time to have a first-hand experience of what Crone’s thesis is about. So, in no particular order, and rather quickly, I read God’s Rule: Government and Islam (2004), co-written with Martin Hinds; Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (first published in 1987); Slaves on Horses (1980) and Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World, the book she co-authored with Michael Cook in 1977 and which caused a storm in the rarified circles of scholars. Even though she may have changed her mind since she published the book in 1977, Hagarism and Meccan Trade totally upset the foundations of what we have grown to believe is Muslim history. They show, as do other writers in different ways, like Arthur Jeffery, John Wansborough, and, more recently, Fred Donner, Tom Holland and Robert Spencer, that what Muslims and non-Muslims learn in school about Islam is not facts that happened but literary compositions whose aim was to create a new religion with its own legitimizing mythology.

A Religion is Born

Muslims believe that their Prophet Mohammed, who was born in 570 AD and died in 632 AD, is the best human ever born in the world, chosen by God to spread his final and everlasting message, preserved in a heavenly tablet, the Koran. Starting out from humble origins in Mecca—a bustling crossroads in the caravan trade—and reputed for his honesty and wisdom, Mohammed married his older boss Khadija, received God’s message through the archangel Gabriel at a local cave when he was 40, fled his native city and migrated to Yathrib (thereafter known as Medina) when his persecution grew more intense, and later returned to Mecca as a triumphant Muslim conqueror. By the time he died, he had married several times and most of Arabia had converted to Islam. Soon his followers, known as Muslims, fanned out in a series of conquests (downplayed as futuhat in Islamic apologetics) that, within a century, had reached France and turned the Fertile Crescent, North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula into Muslim nations. Continue reading Islam: The Arab Religion