In 1894 the composer Harry G. Martin wrote a piece of sheet music called “Yemen,” drawing on a stanza in the famous poem Lalla Rookh by Thomas Moore. This sheet music is available online at the LOC website. Below is the first part of the piece:

In 1894 the composer Harry G. Martin wrote a piece of sheet music called “Yemen,” drawing on a stanza in the famous poem Lalla Rookh by Thomas Moore. This sheet music is available online at the LOC website. Below is the first part of the piece:

The latest issue of CyberOrient is now available online:

Joel W. Abdelmoez >> Good Tidings for Saudi Women? Techno-Orientalism, Gender, and Saudi Politics in Global Media Discourse

Anna Piela, Joanna Krotofil, Katarzyna Górak-Sosnowska, Beata Abdallah-Krzepkowska >> The Role of the Internet in the Formation of Muslim Subjectivity Among Polish Female Converts to Islam

and two reviews:

Omneya Ibrahim >> Review: Stein, Rebecca L. 2021. Screen Shots: State Violence on Camera in Israel and Palestine. Stanford University Press.

Michaela Slussareff >> Review: O’Neil, Cathy. 2016. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy

The early major civilizations in the Middle East and Asia with their head start several millennia ago had one thing in common: an agricultural base that fed not only people but led to development of states and their services. Major river systems like the Nile and Tigris/ Euphrates, the Ganges of India and the Yellow of China were important centers for mass production, but at the same time small-scale farmers utilized a variety of water sources or practiced dry farming in a variety of ecozones across continents. Although there were periodic famines due to climate variability or political violence, until the start of the last century many countries were able to grow most of the food needed for their citizens and several were major exporters.

In 1798 Parson Thomas Malthus, an economist in his day, suggested that humanity faced a major food crisis. At that time the world population was around one billion; today it is closing in on eight billion. Malthus argued that population growth, if unchecked, grew at a geometric rate over time, but food production increased only arithmatically; thus it was inevitable that there would be food shortages, especially for the poor. At the time Malthus was unaware of later advances in agricultural technology, but his warning still serves a purpose. There needs to be a way to ensure that any form of food production is sustainable. The so-called "Green Revolution" that prophesied major dams and irrigation schemes as the wave of the future has indeed been a wave, but far more destructive to the environment and local agricultural traditions than anticipated.

If we are to recalibrate the model of Malthus today, it is less a mathematical issue than a bureaucratic one fueled by monopolistic profit making. In the United States about half of all family-owned farms are considered small-scale, but they generate only 21% of production. There has been a general decline in the number of farms in the U.S. from a high of 6.8 million in 1935 to about 2 million in 2021. The problem is even grimmer outside the industrialized West, where overall crop diversity has declined by 75% in a century, in large part due to the domination of commercial seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. Not surprisingly the need for food aid has grown in recent years.

The case of Yemen has become a poster child for food aid since the humanitarian crisis began in a war that started in 2015. As noted by the World Food ProgramThe current level of hunger in Yemen is unprecedented and is causing severe hardship for millions of people. Despite ongoing humanitarian assistance, 17.4 million Yemenis are food insecure. The number of food insecure people is projected to go up to 19 million by December 2022.

The rate of child malnutrition is one of the highest in the world and the nutrition situation continues to deteriorate. A recent survey showed that almost one third of families have gaps in their diets, and hardly ever consume foods like pulses, vegetables, fruit, dairy products or meat. Malnutrition rates among women and children in Yemen remain among the highest in the world, with 1.3 million pregnant or breastfeeding women and 2.2 million children under 5 requiring treatment for acute malnutrition.

Historically, the rich and fertile land of Yemen, stemming back three millennia to the ancient kingdom of Sheba (Saba), was the bread basket of Arabia. During the 13th century, for example, Yemen boasted diverse crop production from the hot and dry Red Sea Coast to cultivated mountain terraces at the highest point on the Arabian Peninsula. One of the ruling sultans, al-Malik al-Ashraf Umar, interviewed local farmers and wrote a major treatise of the agriculture practiced in Yemen in his time. There were, of course, periodic famines, but overall Yemeni farmers were able to feed themselves and export grain north to Mecca. After the civil war in the 1960s toppled the long-lasting Zaydi imamate, the resulting republic in Yemen’s north received major development aid for improvement of agriculture, but most of this had limited impact at the local level. As the population grew, from less than seven million in 1976 to now reaching 30 million, and unregulated drilling of tubewells drew down aquifers drastically, food production has declined precipitously. There is still fertile land and Yemen’s limited water resources can be used in a sustainable manner, but the ongoing war has ground the economy to a virtual halt. Farmers are still growing food, but it is not clear how much. The fact remains that without imported food aid, there would be a massive famine.

While there is little choice not to send massive amounts of food aid to Yemen to meet the emergency, there is also an urgent need to revitalize the rich agricultural production systems of Yemen, many of which rely on dry farming techniques developed over centuries. Current violent conflict makes such an emphasis difficult, but there are opportunities to work with local Yemeni communities and NGOs. The need is not for foreign technical know-how, an approach that has been ineffective and a waste of funding, but to assist Yemenis in rebuilding terrace walls and using their own seeds, especially for food crops like sorghum which grow well at most elevations. Without contributing to Yemen’s food sovereignty, the ability of Yemeni farmers to grow their own food in harmony with the environmental constraints and not overly dependent on foreign inputs, food aid is a bandage on a gaping wound.

One of the main contributors to the decline in traditional varieties of seeds and crops around the world is the corporate monstrosity previously known as Monsanto. Fortunately, Monsanto with its GMO push never made inroads in Yemen, but the results have been negative elsewhere. The destruction from its pesticides and control of seeds has been known for over two decades. The negative impact has been especially hard in India, which the film Bitter Seeds explores. By pushing GMO seeds, especially cotton, that turned out to be problematic and an economic burden, farmers were locked into dependence on imported seeds and this led to a decline in the local seed varieties, many of which were well suited to local environments after centuries of use. The fact that major aid donors such as the World Bank have pushed GMO seeds despite the enormous economic and bureaucratic burdens these impose on developing nations, has reduced rather than aided food production, especially given the focus on cotton. Regardless of the negative health impact of GMO foods, the overriding issue is saddling local small-scale farmers worldwide with expensive, imported production needs and has devastated locally adapted crop varieties.

Anthropologist Joeva Sean Rock has just published an ethnographic study entitled We are not Starving: The Struggle for Food Sovereignty in Ghana. He shows that despite the promise of improved cotton varieties, the results were far less promising and actually disrupted local food production, which has been predominantly small-holder. In addition, by talking to Ghanian farmers and activists, he realized that the food aid providers started with the assumption that local farmers did not know how best to farm and they needed foreign assistance or they would starve. Instead of working with farmers to build on their knowledge honed over centuries through all kinds of climate change, they simply presented an unsustainable package deal with strings attached from the outside.

The lesson for the future of Yemen’s agriculture is obvious. Yemeni farmers have been successful in small-scale food production for centuries. While no one is proposing going back to reliance on simple scratch plows and animal labor as a permanent solution, the old systems can be built on and updated with appropriate changes. A major proponent of responsible change is the Yemeni NGO YASAD, the Yemeni Association for Sustainable Agricultural Development, the activities of which have been curtailed as the Yemen war wages on. Food aid must continue to avert famine, but aid to revitalize Yemeni farmers’ food production is just as urgent a need. Major donors like the World Bank, UNDP and FAO, USAID and all other interested agencies should find ways to help Yemeni farmers and local communities directly, not by imposing outside methods but allowing Yemenis to expand on their own successes.

Daniel Martin Varisco is an anthropologist and historian who conducted ethnographic research on highland springfed irrigation in Yemen in 1978-1979 and returned more than a dozen times as a development consultant and historian. He is currently translating the 13th century agricultural text of al-Malik al-Ashraf and other Rasulid documents on agriculture.

This post was republished on Informed Comment: https://www.juancole.com/2022/09/sovereignty-farming-suffers.html

This is a fabulous new book from the University of California Press discussing photographs from late 19th and early 20th century Palestine from seven notebooks by Wasif Jawhariyyeh (1904–1972) that contained some 900 images. And it is available for download as open access. Below is one of the images, as well as a flyer for a concert in Jerusalem by Umm Kalthum. Check it out…

Long before Abraham/Ibrahim left Ur of the Chaldees for the promised land and became the ancestral icon of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, there was that architectural wonder called the Tower of Babel. As noted in the eloquent phrasing of the King James Version of Genesis 11:4: “And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” Readers of the text know what happened with that bravado venture. As a refresher, here is how the artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder imagined that ziggurat tower in 1563.

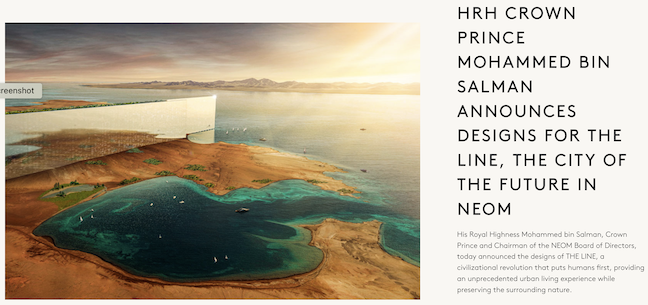

Now what if instead of a massive tower, such an old-fashioned idea, a new world wonder was created with the narrow ribbon of an artificial skyscraper city some 75 miles long, and some 656 feet wide? One set of plans would make this the most eco-friendly living space ever conceived:

THE LINE will eventually accommodate 9 million people and will be built on a footprint of just 34 square kilometers. This will mean a reduced infrastructure footprint, creating never-before-seen efficiencies in city functions. The ideal climate all-year-round will ensure that residents can enjoy the surrounding nature. Residents will also have access to all facilities within a five-minute walk, in addition to high-speed rail – with an end-to-end transit of 20 minutes.

This rival to The Pyramids would reach 1600 feet into the sky, thus becoming taller than the World Trade Center that several Saudi citizens destroyed in 2001 by crashing an airplane into the building. Of course such a major building enterprise would cost a lot of money, like a trillion dollars. I wonder what country would have that kind of funding available and what kind of resurrected Nimrod would think of such an idea?

Guess what? The plans are now on the board with the NEOM project known as “The Line”. You can read all about it on all kinds of websites, like NPR, The Independant, The Guardian, Time Out, and many other sources by typing “NEOM The Line” into Google. The patron of this marvel is His Royal Highness (I guess the Highness in his title inspired the idea to have the highest city in the world) MBS of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It would have been nice to read a review of this fiasco by the Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi, but he is no longer around.

Of all the places on earth, where would be the best location for this ethereal construction project? Why not at the crossroads of the planet? Now that all roads no longer lead to Rome, I guess that would be the Arabian desert in Saudi Arabia. After all who would not want to live in a natural setting with miles and miles of sand and rocks and hardly any sign of wildlife? Unfortunately there are only a few camels left in the Saudi desert, since most are now getting ready for beauty pageants. But at least there will not be the nuisance of fast-driving joy-riding by Saudi youth through the streets, since there will not be any streets. Instead, I suspect that people will get around by doing what they did on the TV show The Jetsons. Of course, Saudi lifestyles will still be enforced, so women will need a male escort and be veiled before taking that five-minute walk to anything they desire.

World reaction to this marvel of marvels is just beginning. Carlos Felipe Pardo informed NPR that “This solution is a little bit like wanting to live on Mars because things on Earth are very messy.” The choice of Mars is proper, since Venus would not be a good metaphor for Saudi censors due to all the naked images of the goddess Venus that are available on the web. I think there would be a positive response from endangered dictators like Vladimir Putin, since the Saudi government has given sanctuary to all kinds of nasty rulers in exile in the past, most recently Ben Ali of Tunisia. Idi Amin, the brutal ruler of Uganda, but clearly thought to still be a good Muslim in the Saudi style, spent his latter years in luxury as a guest of the Saudis.

The Tower of Babel was doomed from the start, but then Nimrod and his like did not realize the vast oil and gas wealth underneath their feet in the Middle East. If they had, we would all be speaking the same language that Adam and Noah spoke. Even Star Trek never imagined that.

There is an excellent analysis in Time Magazine of how President Biden’s trip to the Middle East could help with resolving the protracted war on Yemen. You can read it here.

Omar Dewachi, an anthropologist who was an Iraqi physician during the Gulf War, has published an article from his forthcoming book, which is entitled “When Wounds Travel: Ecologies of War and Healthcare East of the Mediterranean”.

Here is the start of the article. To read the whole article, click here.

A call from the surgical residence in the outpatient clinic informing us of a new admission to the ward. “It is a burn case,” he warns, “Najwa Abdul Hadi, female, in her early 30s, transferred from a local hospital with burn injuries covering nearly 90% of her body following the explosion of a cooking gas container at her home.” Mohammed and I, the two junior doctors on the floor, rushed to the other side of the ward, impatiently waiting at the service elevators to receive our new admission. Only days into our surgery rotation on the second floor of Baghdad Teaching Hospital—Iraq’s largest referral hospital and medical complex—we had finished medical school a month earlier, in May 1997. This was our first job as “real” doctors. Unlike Mohammed who had studied medicine at another med school, I had spent the past 6 years of my training in this teaching medical complex, and was familiar with the ins and outs of the hospital. Still, this was a new terrain for me. No longer a student, this night was my first time “on call”, and I was getting a bit anxious.

For many of us who lived through the first Gulf war, the sight of a burnt body became a doppelgänger of that war. One such doppelgänger was the charred body of one Iraqi soldier in the carnage of tanks which littered what became known as the “Highway of Death”—where the retreating convoys of thousands of Iraqi soldiers from Kuwait were attacked by the US military with Depleted Uranium (DU) weaponry. DU was developed in the US during the Cold War era and experimented with for the first time in real combat during the 1991 Iraq War. It was designed to burn through thick metal surfaces, namely tanks and fortified armored vehicles. The artillery tips burn through the thick alloy, incinerating them inside and out upon impact.

Another image of that war, which I witnessed for myself, was the silhouette of two skeletal remains fossilized into the concrete walls inside the famous Amiriya Shelter, where 408 people were killed with so-called bunker busting, “smart bombs.” US pilots nicknamed them “the hammer” for their massively destructive capabilities and wide-ranging blast radii. I visited the Amiriya shelter in 1991 after the cessation of the bombing campaign. I remember thinking that it was a blessing that those in the bunker did not suffer for long. It was more merciful and dignified to die on the spot than to endure the effects of surviving such brutalization.

I am pleased to announce the publication of my new book: Seasonal Knowledge and the Almanac Tradition of the Arab Gulf. Details about the book, including a free online pdf of the table of contents can be obtained here: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-95771-1

Below is the start of the Introduction…

Before the middle of the twentieth century, everyday life in the Arab Gulf was oriented to the sea and the land. Along the coast and for the island of Bahrain there had been a thriving pearl diving industry until the 1920s, while fishing remained one of the most important food production activities. Trade around and beyond the peninsula was still largely carried out by traditional dhows. Apart from Oman, which has a long tradition of irrigated and rainfed agriculture, most of the Gulf states faced a harsh, arid environment with limited water and only a few fertile oases. Herding of camels, sheep and goat was one of the main ways of surviving in the arid areas. It should not be surprising that prior to the oil wealth that created a lush economic transformation, the main topic of concern was the weather. Successful navigation, pearl diving and fishing required an intimate knowledge of seasonal change, as did pastoralism and farming.

Information on the seasonal sequence for the Arabian Peninsula stems back over a thousand years in collections of poetry, star lore and almanacs. One of the most important Arabic texts is the Kit?b al-Anw?’ (Book of Weather Stars) of Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/879), who is quoted by almanac compilers in the Gulf to this day. Ibn Qutayba describes in detail local knowledge about star risings and settings, weather seasons, pastoral activities, agriculture and a range of environmental conditions. Unfortunately, much of this indigenous heritage has disappeared, as the folklore of generations is now rarely passed on orally within families. In recent years older individuals in the Gulf have written memoirs, preserving their knowledge of life before the Petro Utopia. This gives us a glimpse of the past, a puzzle with many missing pieces, but not the full understanding that comes with actual contact.Resurrecting the history of seasonal knowledge in the Arab Gulf and the entire Arabian Peninsula thus requires a textual archaeology. It is not enough to simply document what is written, as though one is showing off museum objects; this knowledge needs to be placed into a lived context to have a better understanding of how people went about their lives off the land and on the sea.

The past is like an ocean in which we can sample only a small part of the vast number of ideas and customs that have passed by over the years. To follow this metaphor, most of our sampling is along the shore, learning from individuals we can ask directly or engage with in ethnographic fieldwork. We can only cast our research net a short distance in trying to reach back into what really happened and was said in the past. A historian can sail as well, dropping an anchor where there seems to be something worth exploring. But there are depths in this ocean of knowledge that can never be reached. There are also reefs, barriers that make it difficult to have smooth sailing through our disciplined search for the past. To what extent can we know what local knowledge was shared? Then there is the question of what kind of fish we are trying to catch. Is everything that has been done and said, no matter how many generations back, something we should call “heritage”? If we read about it in a book, even one written centuries ago, does that automatically make it “heritage”? How can we vouch for the accuracy of what has been written down when we cannot see it for ourselves or question the interpreter? These are not insurmountable hurdles, but they do caution us to recognize the limitations of reconstructing the past.

My career as a scholar began in the highland mountains of Yemen, where I carried out ethnographic research on traditional water resource use and local agriculture in the late 1970s. Talking with farmers and observing their work for over a year allowed me to gain an understanding of local practices that no book could give me. While in the field I had access to a fourteenth century Yemeni agricultural text, which described many of the agricultural activities I was seeing for myself. My first book was an edition and translation of a thirteenth century Yemeni agricultural almanac. Over the years I have become what is best called a historical anthropologist, someone who looks at heritage as a product evolving from a past and not simply what one sees, without hindsight, functioning in the present. As an anthropologist I focus on the diversity of what people do and say, giving voice to them rather than plugging them into an outside theoretical package from the start. As a historian I have an opportunity in examining texts to see the strands of past knowledge that survive and still influence the present.