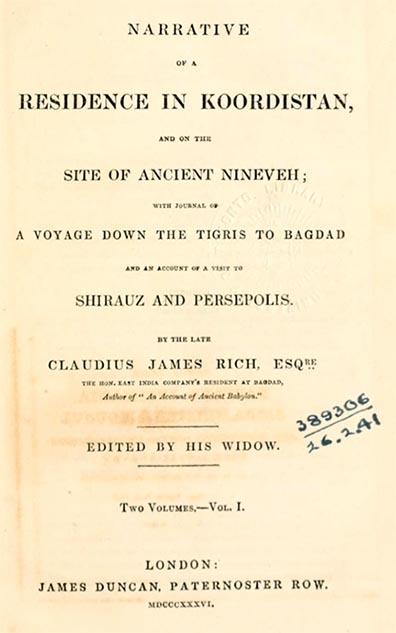

Old travel books never cease to delight me. While century-and-more books used to be available mainly in rare book collections of major libraries, the magic of archive.org brings digital life to the genre. Take, for example, the travel account of Claudius James Rich, whose 1820 trip from Baghdad, where he was posted as a British diplomat, to Kurdistan is a fascinating account of the Kurdish area almost two centuries ago. Born on March 28, 1787 near Dijon in Burgundy, the lad grew up in Bristol, England. He was tutored in Greek and Latin, but at the age of eight or nine he saw a book in Arabic and his appetite was whetted. By the age of fifteen, he had made great progress in Arabic, Hebrew, Syria, Persian and Turkish. Rich came of age when “Oriental Studies” carried no stigma. In 1804 he made his way through Malta and Italy to Istanbul and Egypt.

Like Burton, who would follow, Rich dressed as a Mameluke and left Egypt for Palestine and Syria. In Damascus he visited the Great Mosque. Then on he trekked to Aleppo and Baghdad before continuing on his way to India, where he arrived in 1807. A year later he married and set off to be the British Resident in Baghdad. He was an avid collector of manuscripts, many of which ended up in the British Library, coins and antiquities. He was one of the first Englishmen to describe the ruins of Babylon. His health began to deteriorate in 1813 and by 1821 he died of cholera in Shiraz.

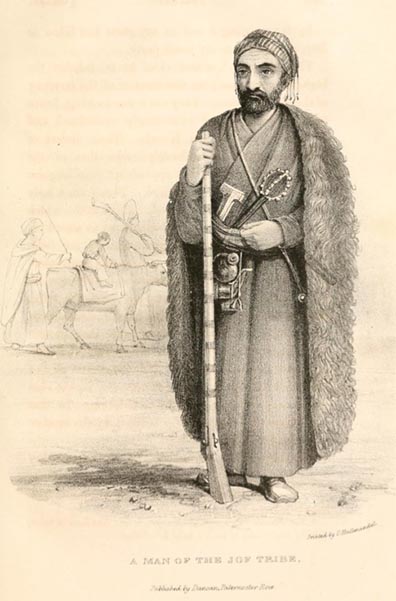

Among the people he met in Kurdistan were important members of the Jaff family, as he describes below: