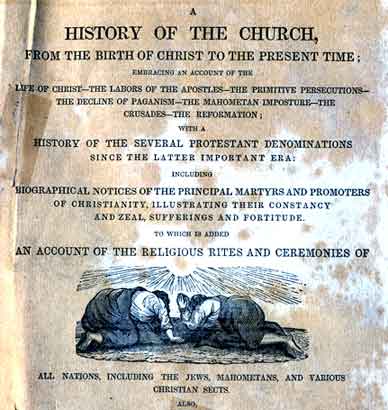

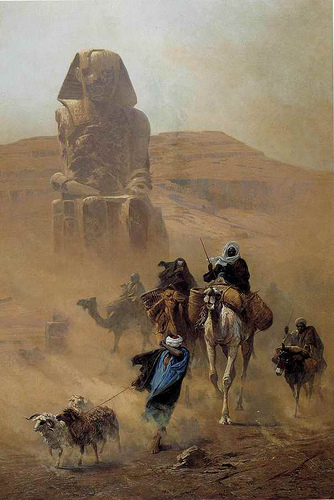

Jaffa from Thomson’s “The Land and the Bookâ€

Almost 150 years ago one of the most popular travel accounts of the Holy Land was penned by an American missionary named William M. Thomson. Born in Ohio, my own home state, the 28-year old Thomson and his young bride arrived in Lebanon in 1834 as Protestant missionaries. This was a mere 15 or so years after the first American missionaries had made the Holy Land a mission field. At once an entertaining travel account and Sunday School commentary on the places and people of the Bible, this may have been one the most widely read books ever written by a Protestant missionary.

Reading Thomson is like reading one of the early English novels. The language is less familiar, although still thoroughly Yankee and the devotional tone has long since disappeared for a readership buying out The Da Vinci Code as soon as it hit the bookstores. The biblical exegesis, literalist yet frankly pragmatic at times, is intertwined with astute and at times humorous accounts of the people Thomson met along the way. But the style is not at all dry or discouragingly didactic. From the start Thomson engages in a dialogue with the reader, making the text (which stretches over 700 pages in the 1901 version) a rhetorical trip in itself.

Here is one of the forgotten books of a couple generations back. Easily dismissed as an Orientalist book, in the sense propounded and confounded by Edward Said, it is nevertheless a very good read. With this post I begin a series to sample the anecdotes and local color presented by Rev. Thomson. The times have indeed changed, but such textual forays into the night reading of a previous generation of Americans are well worth the effort. Let’s begin with the author’s own invitation. Continue reading Tabsir Redux: The Land and the Book #1: Looking for an Omnibus?