Notes from Algeria and Turkey — Charting the Modern Face of Islamic Civilization and Democracy in a Global World

by Bruce Lawrence, Transcultural Islam Research Network, November 30, 2012

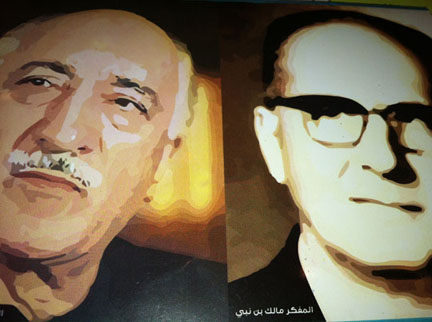

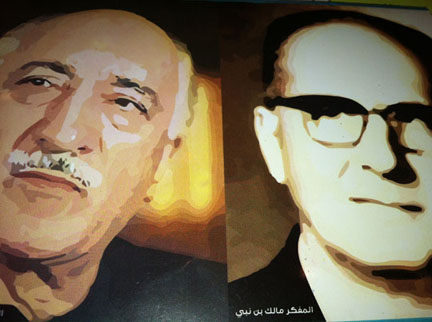

What can we learn from an aging Turkish Imam with a pan-Turkish cultural movement to his name and a deceased Algerian philosopher — both of whom command attention as devout Muslims and men of science — about civilizational rebuilding in the modern era?

Scholars gathered in Algiers from Nov 21-22 at the College of Islamic Sciences at the University of Algiers to find out.

“The Philosophy of Civilizational Rebuilding, according to Malek Bennabi and Fetullah Gülen: Guidelines for Creative Thinking & Effective Action†was the theme for the conference, and I was invited to give a paper on this weighty subject.

I had been teaching in Istanbul during Fall 2012. My assignment there had been to train graduate students, both Turkish and non-Turkish, in theories and methods that apply to civilizational studies.

I had also been traveling and giving lectures elsewhere in Turkey, including a memorable lecture to 400 students at Mustafa Kemal University in Antakya — where the topic was Islam and Global Civilization and included a survey of constitutionalism, citizenship and cosmopolitanism, along with numerous approaches to Islamic civilization in the crowded marquee of world civilizations that claim to be both global and universal.

Just who were Fethullah Gülen and Malek Bennabi? Why was their thinking paired to address the topic of civilizational rebuilding, and how would their views advance an initiative that spanned centuries and engaged some of the best minds, from Ibn Khaldun in late 14th century North Africa to Arnold Toynbee in mid-20th century Britain? Continue reading Notes from Algeria and Turkey →