Joseph Massad: an Occidentalist’s Other Subjects/Victims

by S. Taha, The Arab Leftist

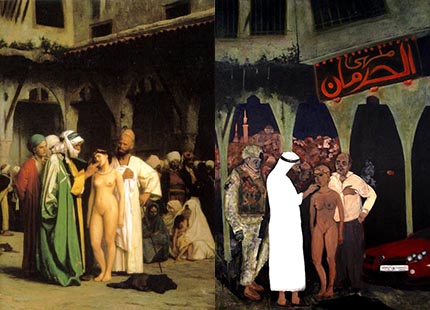

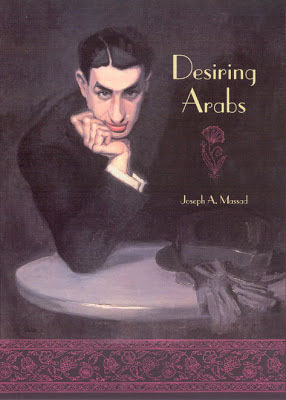

Joseph Massad, an associate professor at Columbia University and a now prominent figure in the US academic field of Middle Eastern studies, came to acquire his status through a hotly debated and highly acclaimed book, Desiring Arabs. Massad, who claims to be the disciple of another foundational academic figure from Columbia, Edward Said, seeks to complete his patron’s Foucauldian project on Orientalism. Said, who strikes me as a much more modest, engaged and consistent intellectual than his self-styled “discipleâ€, is best known for his critical study of “Orientalism,†which looks into the representation and construction of the “East/Orient†as Other to the Western/European self, a construction that, as Said had shown, was deeply engaged with the process of modern imperial expansion and colonialism. This process of domination was what both produced the European “will to know†the subject “Other†and enabled its realization “in an increasingly profitable dialectic of information and control.†However, while employing Michel Foucault’s analytical grid of power/knowledge and his methods of discourse analysis, Said’s project remains incompletely Foucauldian, since it does not probe into the effects of the colonial discursive regime of power/knowledge on the formation of the modern Arab subjects who languished under it for centuries. Therein, Massad makes his academic intervention and contribution, armed with Foucault’s conceptual tools to investigate sexual identities and subjects as effects and products of colonial power. Such territory of “subject formation†under colonialism, which Massad has ventured into is indeed an extremely slippery and delicate one, fraught with questions of agency and subjectivity, since it is not only an investigation into the workings of colonial power, but rather into the very subjectivity and the very being of those whom power represents and brings into its domain and universe of discourse. It is an investigation into the relationship between Western and non-Western, between colonizer and colonized with all that an interrogative representation of such relationship might, adverdantly and inadverdantly, entail about the truths, histories and identities of the two sides of the imperial divide. Continue reading Less than Desirable Review of “Desiring Arabs” →