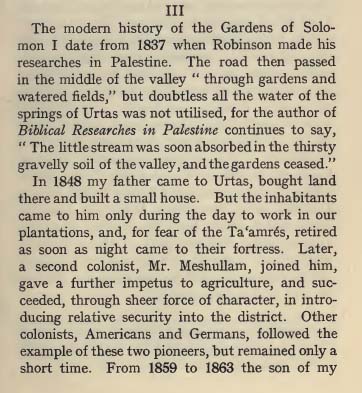

As begun in a previous post, here is another excerpt from Philip J. Baldensperger’s The Immovable East, published in 1913, and available for free as a pdf at archive.org.

As begun in a previous post, here is another excerpt from Philip J. Baldensperger’s The Immovable East, published in 1913, and available for free as a pdf at archive.org.

As begun in a previous post, here is another excerpt from Philip J. Baldensperger’s The Immovable East, published in 1913, and available for free as a pdf at archive.org.

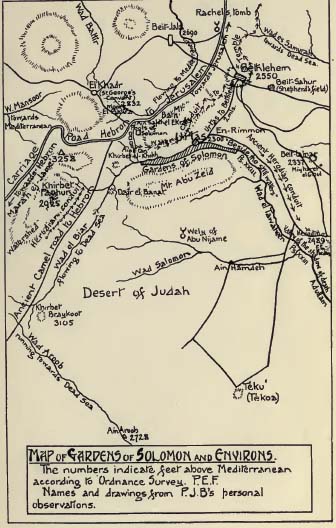

The land currently contested by Israelis and Palestinians has a long history of being contested. In the 19th century, when the area was under Ottoman control, several foreign missionaries settled in the land where Jesus walked. Philip J. Baldensperger, born in 1856, was the son of an Alsatian missionary living near Jerusalem. As a boy who grew up in Palestine, he learned first hand many of the customs and wrote his observations down. His magnum opus is The Immovable East, published in 1913, and available for free as a pdf at archive.org. I attach here the introduction to the work by the bibliophilic Frederic Lees. The pictures are well worth looking at the text, which is a fun read with banal Orientalist trimmings of an area where politics rules the day as never before.

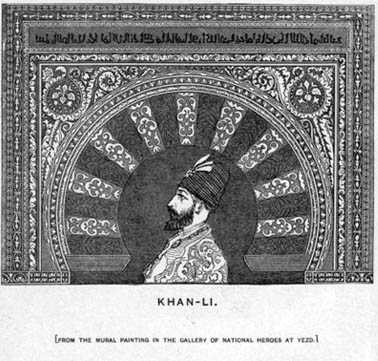

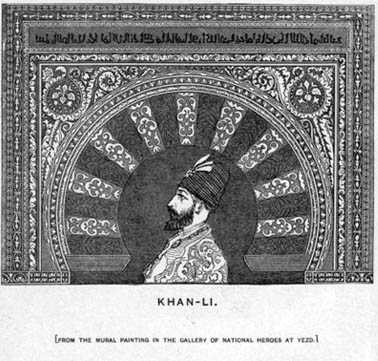

There was a time when “Oriental Tales” were the rage of the age. Montesquieu penned Lettres Persanes in 1721 and Oliver Goldsmith followed up several decades later with The Citizen of the World. But I recently came across a late 19th century text about a future visit of a Persian Prince and Admiral to the ruins of a land known as Mehrica. This is The Last American and purports to be the journal of Khan-Li, a rather bizarre name for a Persian but so thoroughly Orientalist in mode. The Introduction to the text was provided in a previous post.

It is quite apt that the epigraph for the book is a dedication to “the American who is more than satisfied with himself and his country.”

Given the recent “Occupy Wall Street” interest, here is a century old look at what it might have been in ruins…

Continue reading The Last American #2

There was a time when “Oriental Tales” were the rage of the age. Montesquieu penned Lettres Persanes in 1721 and Oliver Goldsmith followed up several decades later with The Citizen of the World. But I recently came across a late 19th century text about a future visit of a Persian Prince and Admiral to the ruins of a land known as Mehrica. This is The Last American and purports to be the journal of Khan-Li, a rather bizarre name for a Persian but so thoroughly Orientalist in mode. The admiral visits America in 1990 ( a century after the book was written), when American is in ruins, following the massacre of the Protestants in 1907 and the overthrow of the Murfey dynasty in 1930. But let the introduction to the text set up the marvels…

Arbuckles’ Ariosa (air-ee-o-sa) Coffee packages bore a yellow label with the name ARBUCKLES’ in large red letters across the front, beneath which flew a Flying Angel trademark over the words ARIOSA COFFEE in black letters. Shipped all over the country in sturdy wooden crates, one hundred packages to a crate, ARBUCKLES’ ARIOSA COFFEE became so dominant, particularly in the west, that many Cowboys were not aware there was any other kind. Keen marketing minds, the Arbuckle Brothers printed signature coupons on the bags of coffee redeemable for all manner of notions including handkerchiefs, razors, scissors, and wedding rings. To sweeten the deal, each package of ARBUCKLES’ contained a stick of peppermint candy. Due to the demands on chuck wagon cooks to keep a ready supply of hot ARBUCKLES’ on hand around the campfire, the peppermint stick became a means by which the steady coffee supply was ground. Upon hearing the cook’s call, “Who wants the candy?” some of the toughest Cowboys on the trail were known to vie for the opportunity of manning the coffee grinder in exchange for satisfying a sweet tooth.

While sorting through a bevy of late 19th century advertising cards and magazine illustrations collected by my great, great aunt in several yellowing albums, I came across several for the Middle East that were published for Arbuckle’s coffee. Continue reading Tabsir Redux: Mocha Musings #1: Mecca and Arabia

The primary international professional association of scholars who study the Middle East is MESA, the Middle East Studies Association. If you go to the main website, you will read:

The Middle East Studies Association (MESA) is a private, non-profit, non-political learned society that brings together scholars, educators and those interested in the study of the region from all over the world. From its inception in 1966 with 50 founding members, MESA has increased its membership to more than 3,000 and now serves as an umbrella organization for more than sixty institutional members and thirty-nine affiliated organizations. The association is a constituent society of the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Council of Area Studies Associations, and a member of the National Humanities Alliance.

Members of MESA receive two journals, the flagship International Journal of Middle East Studies and the revamped Review of Middle East Studies. Each year MESA holds an annual convention, this year in Denver. As noted, the association is non-political and contains members with widely divergent views on the controversial political and religious issues in the Middle East and North Africa.

So, why, you might wonder, is there a rival organization known as ASMEA, The Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa, with its own journal housed with Taylor and Francis? Ah, politics. The founding fathers of the association are Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami, who appear to have joined forces primarily because of a common distaste for the work of Edward Said and their unfailing attraction to the intelligence community. The welcome message suggests that ASMEA is filling a gap:

ASMEA is a new academic society dedicated to promoting the highest standards of research and teaching in Middle Eastern and African studies, and related fields. It is a response to the mounting interest in these increasingly inter-related fields, and the absence of any single group addressing them in a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary fashion.

Like MESA, it claims to be non-partisan, although it is hard to explain why having only one point of view constitutes being non-partisan. It is obvious that scholars, like everyone else, will have differing opinions about issues like Palestinian statehood, inflammatory religious rhetoric, gender and a variety of issues that call for better understanding through dialogue among scholars. But ASMEA is monologue on top of being superficially trite. The claims for the “highest standards of research†are laughable, given the contents of its journal. For example,the most recent issue contains one book review. The chosen book is Rock the Casbah: Rage and Rebellion across the Islamic World by Robin Wright. The author of the book is a reporter, well-traveled (140 countries and counting) and with a prolific presence on all the media. With due respect to the importance of journalism in a free society, Ms. Wright is not an academic scholar; nor has her book been published through the peer review vetting of an academic press. I am not concerned with the value of her book, but it is the kind of book that routinely gets reviewed in major media outlets and rarely in academic journals. Is this the only book that ASMEA could find worth reviewing? [Update: In my original post I misidentified Stephen A. Emerson as Stephen Emerson, an unabashed partisan who sees jihadist terror behind every Islamic-looking bush.] Continue reading ASMEA: ASinine and MEAn

Lady Isabel Burton, wife of Sir Richard Francis Burton

[The following is an excerpt from The Romance of Lady Isabel with her reflections on visiting Jedda on the way to India in 1876. The entire book is available online.]

I was delighted with my first view of Jeddah. It is the most bizarre and fascinating town. It looks as if it were an ancient model carved in old ivory, so white and fanciful are the houses, with here and there a minaret. It was doubly interesting to me, because Richard came here by land from his famous pilgrimage to Mecca. Mecca lies in a valley between two distant ranges of mountains. My impression of Jeddah will always be that of an ivory town embedded in golden sand.

We anchored at Jeddah for eight days, which time we spent at the British Consulate on a visit. The Consulate was the best house in all Jeddah, close to the sea, with a staircase so steep that it was like ascending the Pyramids. I called it the Eagle’s Nest, because of the good air and view. It was a sort of bachelors’ establishment; for in addition to the Consul and Vice-Consul and others, there were five bachelors who resided in the building, whom I used to call the “Wreckers,†because they were always looking out for ships with a telescope. They kept a pack of bull-terriers, donkeys, ponies, gazelles, rabbits, pigeons; in fact a regular menagerie. They combined Eastern and European comfort, and had the usual establishment of dragomans, kawwasses, and servants of all sizes, shapes, and colour. I was the only lady in the house, but we were nevertheless a very jolly party. Continue reading Lady Burton in Jeddah