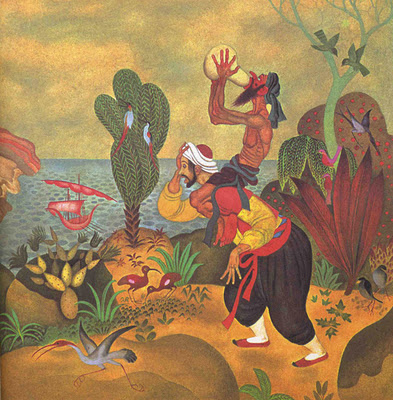

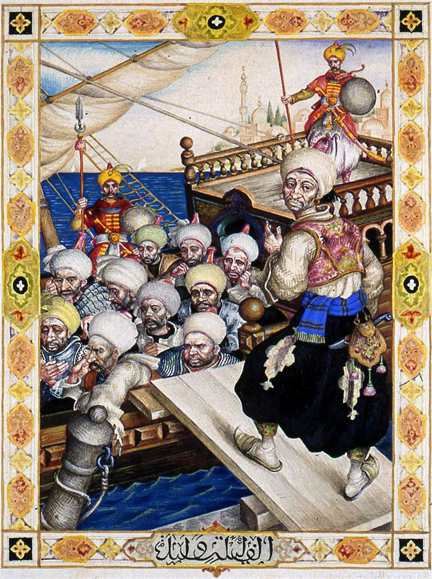

Sinbad’s Seventh Voyage by Arthur Szyk

[Webshaykh’s Note: This last semester I taught an Honors Seminar on the Arabian Nights. The last assignment asked students to write the 8th voyage of Sindbad, drawing on what happened in earlier voyages. I will post several of these here for your enjoyment. This is the second one I am publishing and it is by Marissa Priest. For the first by Taryn Teurfs, click here.]

The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad

By Marissa Priest

Before all the hairs of his beard could turn white, Sinbad the Sailor longed for one last voyage. Yet after all the turmoil of his past adventures, his wife was worried for his safety. Her concern only multiplied when their young son Hamza showed the same symptoms of wanderlust. Like his father, he longed to sail the seas to gather wealth and taste adventure. Despite her pleading, the two set off to begin the eighth voyage. First, Sinbad took his son with him to the docks to gather a reliable crew. They found plenty of honest and faithful men who were eager to set out with the fabled Sinbad. After gathering enough supplies, the men sailed out with no idea where they would find themselves.

Sinbad had chosen a mighty ship, but she was not strong enough to last the force of a great sea storm. As the great waves pounded across the ship, the men were tossed back and forth. Many were thrown into the sea to perish. Provisions flew off the ship and broke apart in the ocean. Sinbad was not afraid, but clung to the mast and instructed his son to do the same. Catching some rope that flew past him, Sinbad tied himself to the mast. Before he could secure his son, the ship capsized. The dominant water swept his son away, carrying him far out of sight. Despite his cries, Sinbad was subject to the ocean’s whims as well. Still bound to the now broken mast, he bobbed across the vicious water for days until being spat out on the shore of a foreign island. After untangling himself from the wet rope and shattered wood, Sinbad rose to study his new surroundings. Continue reading The 8th Voyage of Sindbad: #2