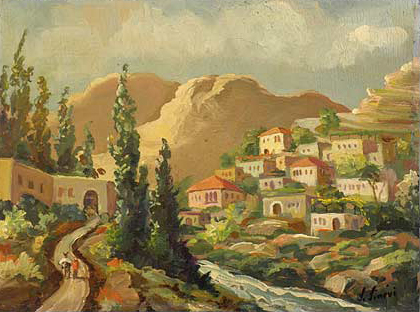

Lebanese village by Saadi Sinevi

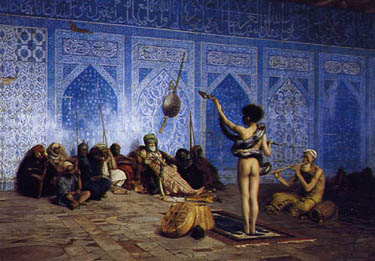

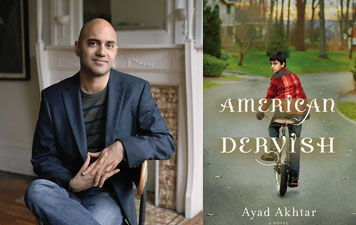

by George Nicolas El-Hage, Ph.D.This is part three of a series from my book: The Return of the Hero and the Resurrection of the City, originally written in Arabic and translated by George N. El-Hage and edited by MaryAnn Del Vecchio, Ph.D. For part one, click here. For part two click here.September 1988Monterey, CAThird LetterI plant you in my eyes, a song of virgin longing, and I draw your smile over my sails bound towards the future.I am longing for return, and you are my hope and the eternal truth.Your two hands, my little one, are the cradle of love, and I am but a Sufi drowning in the deluge of meditation.I wear the gown of pain, and my feet are rooted in the glowing clay of creativity.May peace be upon you the day you were born and the day you embraced me and I felt that I held a bouquet of innocence and embraced a flaming sword.Glory be to your miraculous childhood.You are the lamb of peace, the joy of life, the tear of yearning and the hope of resurrection.My letters to you are but the embers of my burning thoughts, for you are the flame of prophecy and the wings of inspiration.You carry me to the world of the unknown and plant me in the fields of lilies and poems.You throw me on the sidewalks of the past and desert me on the shores of faraway islands.There, I metamorphose and transform into tropical plants, exploding with pleasure and burdened with forbidden fruits.I take off the tied gown of civilization and become naught but the flame of truth.I become one with the elements and melt like dew in the eyes of bereaving mothers. Continue reading Letters to My Son, #3