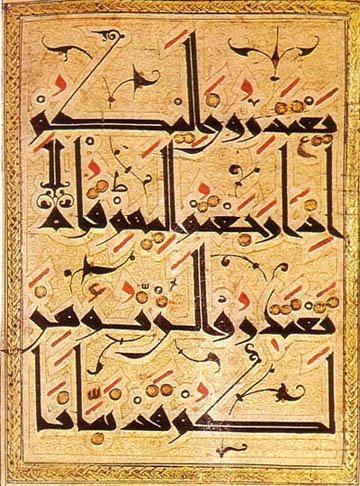

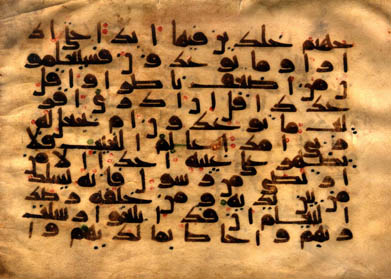

A 9th- or 10th-century leaf of the Qur’an in Kufic script

[The following is part three of a series on a lecture presented in the Hofstra Great Books Series on December 5, 1993. For part two, click here.].

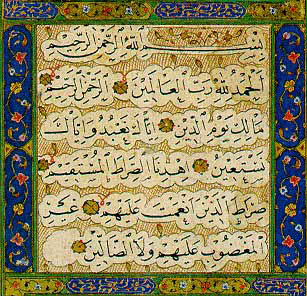

1. Praise be to God, Lord of the Worlds

If there is a phrase in Arabic as frequently used as the bismillah, it is no doubt the hamdillah. Since God is perfect, God alone has the right to receive praise from humanity. God deserves this verbal praise because this mercy comes of his own volition; it was not forced, it was freely given. We are also reminded in these opening words that God rules; he is the rabb of the worlds that be. The word rabb in Arabic has a number of related connotations, including master or lord, chief, determiner, provider, sustainer, rewarder, and perfector. The worlds, perhaps better rendered straightforwardly as the universe, indicated here encompass the material and the immaterial, of flesh-and-blood and of spirits, of those who are well guided and those who are misguided. Whatever is, God is the ultimate master of it. While a non-believer might read this as a base for fatalism, a Muslim sees it differently as a fundamental reason for hope. God’s will will be done, but this hardly frees the believer from doing his or her part, particularly when no one can speak definitively as to what God’s will is in a given matter. The meaning of Islam, after all, is submission.

2. The Compassionate, the Merciful

3. Master of the Day of Judgement

The term malik is that which is used in Arabic for the master of a slave, the owner of property, and the king or sole ruler. For the Muslim, God is the ultimate master of all things. He is not just a judge dispensing justice; God renders reward and punishment (the implication of judgement day) because He alone is the authentic source for such judgement. Who else has this kind of authority, but the one who creates everything and sustains everything? We are reminded quite literally as well that Islam preaches a final judgement, one beyond the grave, a future resurrection of the dead – an idea hardly unique to this revelation. But the Muslim is consoled by the realization that no matter how bad things are (and in many Muslim countries, things are pretty bad right now) God will be the ultimate judge. Continue reading The Quran as a Great Book: Muslim Perspectives, 3