by Faisal Devji, Political Theology Today, August 2, 2013

I want to argue here that the term “political Islam†is in many ways a misnomer, because the Islamism that is meant to instantiate it has been unable to appropriate politics as a way of dealing with antagonism either institutionally or even in the realm of thought. Looking in particular at the form Islamism took with one of its founding figures, the twentieth century writer, and founder of the Jamaat-e Islami in both India and Pakistan, Sayyid Abul a’la Maududi. I shall claim that it is marked by the absence of politics, or rather by a failure to theorize and absorb it. And this failure, I think, results in actions by parties like the Jamaat that are merely, and sometimes violently, unprincipled or opportunistic, because in them theology always stands apart from the political, however much it may want to embrace the latter. Although the development of this kind of anti-politics is rooted in the history of colonialism and the reactions thereto by Islamist thinkers, here I discuss the paradoxical consequences of such an effort, dealing specifically with Maududi’s conception of sovereignty, in which he comes closest to advocating a “political theologyâ€.

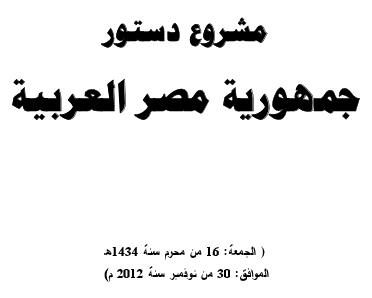

Having examined the legal doctrine of European sovereignty, with all its extraordinary powers, Maududi asks, “Does such sovereignty really exist within the bounds of humanity? If so, where? And who can be construed and treated as being invested with it?â€[1] Sovereignty, he recognizes, can never be fully manifested in political life because it presumes a power too great to be realized, which is to say the mastery of an entire society. In fact if such a power were to be instantiated it could only lead to tyranny. The sovereign, whether king or president, was therefore unable in actuality to exercise the power vested in him, and this difference between what political theory called for and what really was the case could only result in corruption and violence, as “he who is really not sovereign, and has no right to be sovereign, whenever made so artificially cannot but use his powers unjustly.â€[2] Sovereignty, then, properly belongs to God alone, who has sole decision over life and death, since to give such powers to mortals would be to create the possibility of a dictatorship. But “There is no place for any dictator in Islam. It is only before God’s command that mankind must bow without whys and wherefores.â€[3] In an effort to prevent dictatorship of an individual as well as popular kind, Maududi embodies the people’s will in God while at the same times annulling it. For God here is not sovereign in any traditional ways, for instance as the “unmoved moverâ€, but solely as a displacement for the will of the people, which can only manifest itself by identifying with the divine will, and in doing so to un-will itself. In the Islamic state, in other words, Muslims must destroy their particularity by identifying with God’s universality. And even though Maududi never achieved his Islamic state, it was largely because of his doing that Pakistan’s constitution reserves sovereignty for God.[4] Continue reading Islamism as Anti-Politics