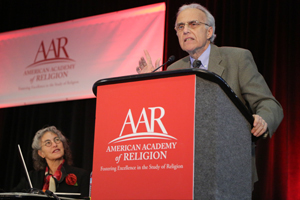

The first part of an interview with Wael Hallaq by Hasan Azad has just been published on al-Jadaliyya. Below is the introduction and the first part of a much longer exchange which can be followed here.

Throughout the last three decades, Wael Hallaq has emerged as one of the leading scholars of Islamic law in Western academia. He has made major contributions not only to the study of the theory and practice of Islamic law, but to the development of a methodology through which Islamic scholars have been able to confront challenges facing the Islamic legal tradition. Hallaq is thus uniquely placed to address broader questions concerning the moral and intellectual foundations of competing modern projects. With his most recent work, The Impossible State, Hallaq lays bare the power dynamics and political processes at the root of phenomena that are otherwise often examined purely through the lens of the legal. In this interview, the first of a two-part series with him, Hallaq expands upon some of the implications of those arguments and the challenges they pose for the future of intellectual engagements across various traditions. In particular, he addresses the failure of Western intellectuals to engage with scholars in Islamic societies as well as the intellectual and structural challenges facing Muslim scholars. Hallaq also critiques the underlying hegemonic project of Western liberalism and the uncritical adoption of it by some Muslim thinkers.

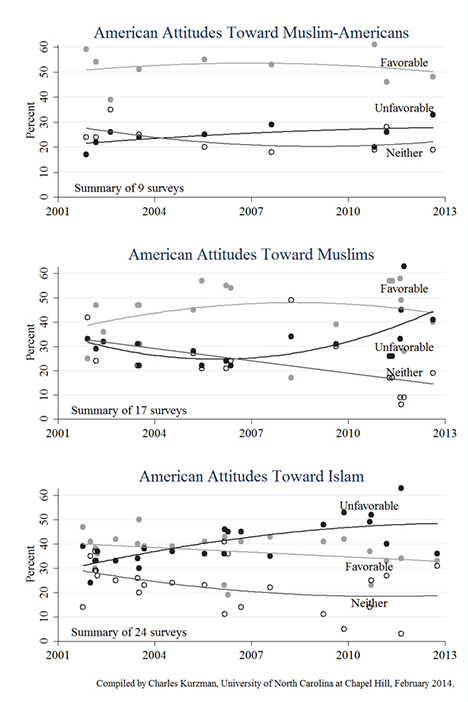

Hasan Azad (HA): One of the debates raging nowadays has been about the inattention that Muslim intellectuals receive in the West. One can say that, with relatively minor exceptions, the modern Muslim presence in, or contribution to, the intellectual world of the West is near nil. In the closing pages of your Impossible State, you have pointed out that a robust intellectual engagement between Muslim thinkers and their Western counterparts is essential, not only for the sake of better Western understanding of Islam, but also for the sake of enlarging the scope of intellectual possibilities in the midst of Euro-American thought. Your argument, I believe, meant to convey the idea that there is much that the Islamic worldview and heritage can contribute toward enriching our reflections on the modern project, in the West no less than in the East. What is that contribution, and why is it not happening? What are the obstacles standing in the way?

Wael Hallaq (WA): To speak of the potential contributions of Islam to a critique and restructuring of the modern project is a tall order, one that should come subsequent to a diagnosis of the present modern condition and its causes. The obstacles you alluded to are numerous and multilayered, and originate in both sides of the divide. If there are any failings—and there are many indeed—they cannot be located on one side only. The first, and most obvious of course, is the linguistic obstacle, the only means to communicating ideas. The West (by which I here mean Europe, its Enlightenment, distinctively modern institutions and culture and the spread of all these mainly to North America), has seen it sufficient to consider its two or three major languages so universal as not to care to learn other languages well, if at all. Even Orientalism, as an academic discipline, has not been successful in producing sustained command of Islamic languages, despite the fact that it did produce individuals whose linguistic competence even in more than one Islamic language was no less than masterful. It remains the case however that those who can navigate an Islamic language or text are a miniscule—in fact insignificant—minority in Western societies.

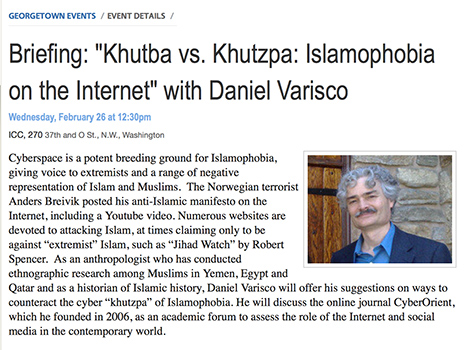

But there is a larger sense to Orientalism involved here. In many ways, the field of Orientalism is surrounded by an outer, immensely extensive layer; that is, countless numbers of influential voices who really never bothered to do any of the hard intellectual and philological work on Islam; yet, they feel quite justified and confident to pronounce on the “Orient,†both within the classrooms of academia or as so-called “experts†in mass media. This “peripheral†Orientalism usually escapes our common definitions of that discipline, but it forms the bulk of common and popular Western knowledge about the rest of the world, especially Islam. In any case, this is roughly the linguistic obstacle.