Nazende al (Flattering Red) from ‘The Book of Tulips’ ca 1725

by Anna Pavord

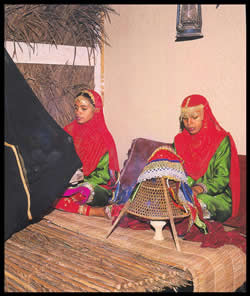

But as in any love affair, after the initial coup de foudre you want to learn more about the object of your passion. The tulip does not disappoint. Its background is full of more mysteries, dramas, dilemmas, disasters and triumphs than any besotted aficionado could reasonably expected. In the wild, it is an Eastern flower, growing along a corridor which stretches either side of the line of latitude 40 degrees north. The line extends from Ankara in Turkey eastwards through Jerevan and Baku to Turkmenistan, then on past Bukhara, Samarkand and Tashkent to the mountains of the Pamir-Alai, which, with neighbouring Tien Shan is the hotbed of the tulip family.

As far as western Europe is concerned, the tulip’s story began in Turkey, from where in the mid-sixteenth century, European travellers brought back news of the brilliant and until then unknown lils rouges, so prized by the Turks. In fact they were not lilies at all but tulips. In April 1559, the Zürich physician and botanist Conrad Gesner saw the tulip flowering for the first time in the splendid garden made by Johannis Heinrich Herwart of Augsburg, Bavaria. He described its gleaming red petals and its sensuous scent in a book published two years later, the first known report of the flower growing in western Europe. The tulip, wrote Gesner, had ‘sprung from a seed which had come from Constantinople or as others say from Cappadocia.’ From that flower and from its wild cousins, gathered over the next 300 years from the steppes of Siberia, from Afghanistan, Chitral, Beirut and the Marmaris peninsula, from Isfahan, the Crimea and the Caucasus, came the cultivars which have been grown in gardens ever since. More than 5,500 different tulips are listed in the International Register published regularly since 1929 by the Royal General Bulbgrowers’ Association of the Netherlands. Continue reading The flower that made men mad →