The following Yemeni poem about qat (Catha edulis), accompanied by the photograph above of a Yemeni girl, was provided by a friend.

The following Yemeni poem about qat (Catha edulis), accompanied by the photograph above of a Yemeni girl, was provided by a friend.

The Yemeni cartoon above says it all: “I read in a book about the harmful health effects from qat and cigarettes, so I decided, God willing, to cease reading.”

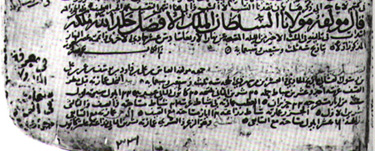

Tax document of al-Malik al-Afá¸al, mid 14th century CE

By Daniel Martin Varisco

[In 2003 I attended a conference in Rome and gave a paper which was eventually published in Convegno Storia e Cultura dello Yemen in età Islamica, con particolare riferimento al periodo Rasûlide (Roma 30-31 ottobre 2003 (Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Fondazione Leone Caetani, 27, pp. 161-174, 2006). As this publication is virtually inaccessible, I am reprinting the paper here (with page numbers to the original indicted in brackets). For the previous part of this article, click here. The references are provided at the end of the first entry.]

ARCHIVING AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS

Al-Ashraf’s Milh al-malÄḥa provides a textbook survey of the mechanics of the agricultural system, but there is nothing on production costs, yields or the marketing system. Fortunately, some microeconomic details can now be filled in with information from the Muẓaffar archive, compiled from field reports sent to the Rasulid court between 691-95/1292-96 at the very end of al-Muẓaffar’s reign. Particularly valuable is a survey made in Ramadan 692/1293 from the lands of a shaykh Muḥammad ibn IbrÄhÄ«m al-Ḥawm (?) of Ta‘izz and shaykh RashÄ«d al-DÄ«n Manṣūr ibn Ḥasan in MikhlÄf Ja‘far, as well as some data from ‘AbadÄn. (26) Details are provided on fees and shares for ploughing and virtually every agricultural activity with special emphasis on the obligations in sharecropping agreements and regional differences.

For the Ta‘izz case, the grain yields of sown sorghum are said to be up to 400 fold (i.e. one zabadī of seed will yield a crop of 400 zabadī) on good land, 150 fold on middle-range land and only 90-100 fold on poor land. Sorghum is also important in Yemen for its stalk (‘ajūr), used as fodder and fuel. The stalk yield for the sowing on good or medium land will be three camel (?) loads, but reaches five loads on land of poor quality; the reason given for this is that such sorghum is grown mainly for its stalk value. [p. 171]

For wheat in Ta‘izz, the increase is 15 fold on good land, 10 fold on medium land and only 3 fold on poor land. Emmer wheat (‘alas), on the other hand, yields 10 fold on good land, 4 fold on medium land and 2 fold on poor soil. Barley is said to yield 10 to 1; this is sown only in the mountain areas and not usually on the best land. Information is also provided on the straw (tibn) yields. Continue reading The State of Agriculture in Late 13th Century Rasulid Yemen, 5

below Manakha towards the Tihama

By Daniel Martin Varisco

[In 2003 I attended a conference in Rome and gave a paper which was eventually published in Convegno Storia e Cultura dello Yemen in età Islamica, con particolare riferimento al periodo Rasûlide (Roma 30-31 ottobre 2003 (Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Fondazione Leone Caetani, 27, pp. 161-174, 2006). As this publication is virtually inaccessible, I am reprinting the paper here (with page numbers to the original indicted in brackets). For the previous part of this article, click here. The references are provided at the end of the first entry.]

PLANTING ADVICE: OF FAVA BEANS AND DATE PALMS

The bulk of al-Ashraf’s text provides details on how to plant and where to plant, as well as when to plant. While some of the information is clearly theoretical, as in the case of planting olive trees, much of it no doubt reflects farmer practices at the time in the coastal region and southern highlands, [p. 168] where al-Ashraf spent most of his time. To give an indication of the range of the advice, I will focus on two specific and important crops: the fava bean and the date palm.

Al-Ashraf follows the classical designation of bÄqillÄ’, which is often shortened to gilla in Yemeni dialects. It would, if you pardon the pun, be foolish of me to lecture this audience on the significance of fava beans (most known today as fÅ«l) in the diet. I will read a translation of the entire passage in the text, followed by comments from my own ethnographic observations. (16)

“Fava beans are planted in cool places of the mountain areas. They are not suitable for the coastal plain [nor the wadis in the cold mountain areas] nor very wild places. The best agricultural fields are in the excellent eastern land on which a lot of dew does not fall, (17) as well as in the good soil (18) which is fertilized by dung. It is ploughed for with an excellent ploughing. Most of it is planted between the sorghum plants in NÄ«sÄn (i.e., April). The beans can be eaten after three months from the day planted. It finishes producing and is harvested after seven months. There is also that which is planted as qiyÄẓ at the end of AylÅ«l (i.e., September) in the midst of the sorghum plants. This can be eaten after four months. It finishes producing and, if it has yellowed and dried, is harvested after seven months. As for the manner of its cultivation, the seed is cast in the bottom of the furrow with a footstep between each two grains, (19) then covered with soil and packed down by foot. When the sorghum is harvested, irrigate whatever it needs of water after this in the same way as for the sorghum stalk, even for that which is meager, until its time finishes, as God wills.†Continue reading The State of Agriculture in Late 13th Century Rasulid Yemen, 4

highland sorghum

[In 2003 I attended a conference in Rome and gave a paper which was eventually published in Convegno Storia e Cultura dello Yemen in età Islamica, con particolare riferimento al periodo Rasûlide (Roma 30-31 ottobre 2003 (Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Fondazione Leone Caetani, 27, pp. 161-174, 2006). As this publication is virtually inaccessible, I am reprinting the paper here (with page numbers to the original indicted in brackets). For the previous part of this article, click here. The references are provided at the end of the first entry.]

IDENTIFYING THE MAJOR CROPS

Although al-Ashraf claims to have learned from the farmers themselves, his overall classification of crops and plants suggests that he is fitting that knowledge into a shared textual tradition of scientific agronomy at the time. Al-Ashraf inventories Yemeni production according to five main categories: zurū‘, qaá¹ÄnÄ« or ḥubÅ«b, al-ashjÄr al-muthmira, rayÄḥīn, and khaá¸rÄwÄt and buqÅ«lÄt. By zurū‘ (the plural of zar‘) al-Ashraf means the cereal crops of wheat, barley, sorghum, rice, two kinds of millet, eleusine (or finger millet) and teff, as well as sesame, cotton, lucerne, madder and turmeric. This goes beyond the English sense of cereal grains to cover the non-food crops of cotton and madder, both of which are reclassified as al-ashjÄr al-muthmira (flowering trees) in the later Bughyat. In classical Arabic terms, at least according to AbÅ« ḤanÄ«fa, sesame is classified as qaá¹ÄnÄ«. (12)

The second major kind of crop is labeled qaá¹ÄnÄ«, which the author glosses as ḥubÅ«b. This includes what we would today call pulses and various kinds of beans, such as chick peas, lentils, cowpeas, fava beans, endive, fenugreek, water cress, mustard, safflower, poppy, flax and black cumin. The term qaá¹ÄnÄ«, according to AbÅ« ḤanÄ«fa, is originally Syrian and refers to crops such [p. 167] as rice, chickpeas, lentils, sesame and most beans. (13) The term ḥubÅ«b (plural of ḥabb) may refer to wheat, barley and the like, but has also been widely used in the agricultural texts for seed plants of various kinds. (14)

The third category, al-ashjÄr al-muthmira, literally refers to flowering trees and plants. (15) In order of presentation, al-Ashraf includes here dates, grapes, figs, pomegranates, apples, plums, pears, peaches, apricots, mulberry trees, olives, walnuts, almonds, pistachios, betel nuts, carob, bananas, sugar cane, citrons, oranges, lemons, lebbek, christ’s thorn and Indian laburnum. The reference to olives is clearly textual, since this tree was not planted in Yemen; nor do I think betel would have been tried outside the royal gardens. The fourth category comprises rayÄḥīn or aromatic plants and ornamental flowers. Of the nineteen specific plants mentioned, most are flowers (such as rose and jasmine), but the list also includes useful herbs such as basil, chamomile and the important dye of henna.

The final part of al-Ashraf’s classification refers to khaá¸rÄwÄt and buqÅ«lÄt. This covers a variety of green and root vegetables such as lettuce, cucumbers, eggplant, carrots, cabbage, garlic, onions, radish, endive, mallow, colocasia, chard, spinach, purselane, celery, okra and asparagus. Among the ground “fruits†included here are melons and gourds, although grapes are considered flowering trees. Also included are several spices, such as ginger, mint, parsley, coriander, dill and cumin, as well as “medicants,†such as balsam, rue, fennel and Indian hemp.

FOOTNOTES:

(12) Ibn Sīda, al-Mukhaṣṣaṣ, Beirut, 1965, v. 11, p. 62.

(13) Ibid, v. 11, p. 62. In KitÄb al-FilÄḥa al-RÅ«miya (Leiden, Or. 414, f. 40) qaá¹ÄnÄ« is defined as summer crops like rice which need the heat and water.

(14) Ibn Sīda, al-Mukhaṣṣaṣ, cit., v. 11, p. 49. For example, Ibn Waḥshiya, v. 1, p. 492 includes fava bean in the category of ḥubūb used for food.

(15) This term is used by Ibn Waḥshiya, v. 1, p. 367.

to be continued

Yemeni tribal farmer in al-Ahjur, Central Highlands

By Daniel Martin Varisco

[In 2003 I attended a conference in Rome and gave a paper which was eventually published in Convegno Storia e Cultura dello Yemen in età Islamica, con particolare riferimento al periodo Rasûlide (Roma 30-31 ottobre 2003 (Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Fondazione Leone Caetani, 27, pp. 161-174, 2006). As this publication is virtually inaccessible, I am reprinting the paper here (with page numbers to the original indicted in brackets). For the previous part of this article, click here. The references are provided at the end of the first entry.]

VIEWING THE FIELD THROUGH AL-ASHRAF’S AGRICULTURAL TREATISE

I begin with al-Muẓaffar’s short-reigned son, al-Malik al-Ashraf YÅ«suf, whose treatise Milḥ al-malÄḥa not only defines the genre of Rasulid agricultural texts but is a primary source for the later, larger and more cosmopolitan Bughyat al-fallÄḥīn of al-Malik al-Afá¸al al-‘AbbÄs, which has been studied in part by the late Professor Serjeant. (5) Milḥ survives in at least two copies, both defective; one is in the Glaser collection in Vienna and the other was discovered in southern Yemen less than two decades ago by ‘Abd al-Raḥīm JÄzm. This consists of seven chapters. The first deals with the knowledge connected to times for cultivation, planting and preparing land. The next five chapters are arranged according to the type of crop or plant, with elaborate details on how each is cultivated. The final chapter, which has not yet been found apart from quotations in the Bughyat, discusses agricultural pests. The information provided on crops is almost exclusively for Yemen, unlike the penchant of the later Bughyat’s author to quote extensively from earlier non-Yemeni sources such as Ibn Waḥshiya and Ibn BaṣṣÄl. Indeed, there is no explicit mention of other texts in Milḥ.

After the obligatory salutation of thanks, al-Ashraf begins his treatise with a poetic quatrain:

Fa-hÄdhÄ kitÄb jama‘atuhu bi-ḥasab al-á¹Äqa wa-al-ijtihÄd

wa-ista‘tab ‘alÄ dhÄlik bi-rabb al-‘ibÄd.

Waá¸a‘tuhu ‘alÄ á¸¥ukm iá¹£á¹ilÄḥ ahl al-ma‘rifa fÄ« al-Yaman

ba‘d al-baḥth ma‘ahum fÄ« kulli mÄ fÄ«hi min á¹£anf wa-fann.

[p. 164] “I compiled this book according to diligence and capability

and solicit for proof of this the Lord of all humanity.

I recorded it from the wise practice of those Yemenis who know

only after research among them for all that is within their classifying and artful show.â€

Continue reading The State of Agriculture in Late 13th Century Rasulid Yemen, #2

Rasulid polo players

By Daniel Martin Varisco

[In 2003 I attended a conference in Rome and gave a paper which was eventually published in Convegno Storia e Cultura dello Yemen in età Islamica, con particolare riferimento al periodo Rasûlide (Roma 30-31 ottobre 2003 (Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Fondazione Leone Caetani, 27, pp. 161-174, 2006). As this publication is virtually inaccessible, I am reprinting the paper here (with page numbers to the original indicted in brackets).]

INTRODUCTION AND SOURCES

[p. 161] About seven and a half centuries ago the second Rasulid sultan, al-Malik al-Muẓaffar Yūsuf ibn ‘Alī, was thrust into power in his youth after his father’s murder, just about the time the Genoan Marco Polo was born. The overlap between the Italian merchant mercenary and mercenary descendant sultan is fraught with irony. Al-Muẓaffar, the untested state builder came to power just a decade before the overthrow of the Abbasid caliphate, which had blessed Rasulid rule as a buffer against the Zaydī imams of Yemen’s northern highlands, while the future Italian diplomat set out on his trek only a decade or so after the Mongols had destroyed Baghdad. Polo was destined to serve an aging Kublai Khan, returning to Italy in 1295, the very year that the seventy-year-old-plus Rasulid ruler died. When Polo referred to the immense wealth of the sultan of Aden, “arising from the imposts he lays†in the Indian Ocean trade, he meant al-Muẓaffar. Marco Polo and al-Malik al-Muẓaffar never met, except in print, but the world that they both embraced was centered on an important trade network linking the Mediterranean and Africa with Persia, India and ultimately the lands of the great Khan.

Fortunately for the Rasulids, the merciless Mongol warriors never reached Yemen, apart from a few individuals who later assisted a Yemeni sultan in compiling a “King’s Dictionary†also known as the “Rasulid Hexaglot.” (1) [p. 162] Yemen also escaped the incursions of crusading medieval knights, although the legacy of Saladin played a major role in defining its political fortunes until the arrival of the Ottoman garrisons and Portuguese galleons in the sixteenth century. My focus is on the zenith of the Rasulid era near the end of the long reign of al-Muẓaffar, the preeminent state-builder of the dynasty. By 1252 he consolidated his hold over the coastal zone (TihÄma), southern highlands and Aden, as well as achieving periodic control over á¹¢an‘Ä’, thus driving the ZaydÄ« imams back to their firm base in á¹¢a‘da. The sultan’s forces in the late 1270s took control, by land and by sea, of the important southern harbors at al-Shiḥr and Dhofar, two important sailing venues along the trade route to the Persian Gulf and India. In 682/1283, despite the ZaydÄ« loyalties of many of the tribes, al-Muẓaffar was able to briefly take hold of á¹¢a‘da, even striking coins there. Military success led to increased diplomatic recognition for the Rasulids; later delegations are described in the chronicles as arriving from Persia, Oman, India and China. Fortunately, al-Muẓaffar was an avid patron of architecture and learning, so that the material and written records of Rasulid activities are quite extensive. (2) Continue reading The State of Agriculture in Late 13th Century Rasulid Yemen

Unnamed tulip from the Turkish ‘The Book of Tulips’, ca. 1725

Webshaykh’s Note: With winter snow buffeting Europe and the Middle East, what better time to think about tulips, an Ottoman treasure that took Europe by storm almost half a millennium ago. There is an excellent book on The Tulip by Anna Pavord (Great Britain: Bloomsbury, 1999), but one of my favorite articles is one that Jon Mandaville wrote for ARAMCO World over three decades ago. The full article is available online, but I provide the first part below.]

Turbans and Tulips

Written by Jon Mandaville. ARAMCO World Magazine, May/June, 1977

Tulips come from Holland. Right? Wrong! Or at least, they haven’t always. Tulips come from Turkey, the only country in the world to call one of its major eras of national history—the years 1700 to 1730—the “Tulip Period.” And how that era got its name . . . thereby hangs a tale.

Tulips, even in the early 18th century, were nothing new to Turkey. Along with other bulbous plants such as the narcissus, the hyacinth and the daffodil, tulips had grown there for centuries, both wild and domesticated for house and garden. The Tulip Period took its name from an established hobby, which started as court fashion, grew into a generalized fad and fancy, and finally became an explosion of unrestrained international speculation in bulbs which buyers never even saw.

It all began when tulips first went to Europe. In 1550, no one in Holland had heard of tulips. Different varieties do grow wild in North Africa and from Greece and Turkey all the way to Afghanistan and Kashmir. Very occasionally they are even found in southern France and Italy, usually in vineyards or on cultivated land, which has led some botanists to speculate that they may have been brought back by the Crusaders.

The Persians were familiar with tulips, but they didn’t domesticate them as thoroughly as the Turks. For centuries they admired the flowers wild. Even as decorative motifs in Persia, they were never as popular as the narcissus, iris or rose.

In Turkey it was different. Continue reading Tulip mania