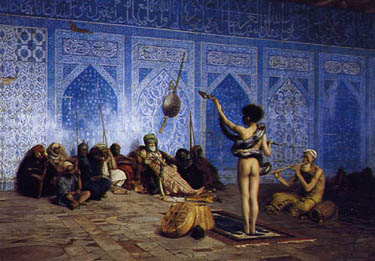

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Le charmeur des serpentes, 1880

In 2007 I published Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid with the University of Washington Press. The build-up to its publishing is a story that spans almost six years. Originally I had planned to include a chapter on Said’s Orientalism in a book I was writing called Islam Obscured: The Rhetoric of Anthropological Representation, which was published in the SAR series of Palgrave in 2005. But as I began to work on the chapter, it quickly took on a life of its own. I had first read Orientalism when returning from ethnographic fieldwork in Yemen in 1979. It sat on my bookshelf and I dutifully included the author’s “introduction†(the most readable part of the book for undergraduate students) in my course on Middle East anthropology. But as I delved back into Said’s book and started collecting the original reviews (which turned out to be more than 50) and the plethora of writings about Orientalism, I discovered that this dense book was fraught with errors of fact and methodological missteps.

While working on both books-to-be, I delivered a paper at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association in 2001 entitled “Dissing Orientalist Discourse: What Said Said and What Ethnographers Did,†followed by talks on my evolving text at the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard, the University of London and New York University. The AAA talk prompted a young employee of Routledge to ask if I was thinking of writing a book on the subject. Naively, I said yes and after another year had a draft ready to drop off in their New York office. Time went by and by and there was no word from Routledge. Eventually, after several months, I received a letter from the Sociology editor noting that Routledge at the time no longer had an Anthropology editor and my manuscript was not of interest to him. I thus learned that there were sociologists who seemed not to know much about Edward Said. But they did send the reviewer’s comments and these were well taken. In fact my first draft was in need of major revision.

So revise I did and then I accidentally stumbled across a website of a book agent inviting queries. Continue reading On the beauty of late medieval florilegium