by Edward E. Curtis IV, Religion Bulletin, May 2, 2014

Editor’s note: This post is part of the Reflections on Islamic Studies series.

By any measure, Islamic studies is a vibrant field. In the last several decades, the number of tenure-track positions dedicated to the study of Islam as a religion and to Muslim politics and societies has expanded. New journals have appeared; book sales are good; and interest in Islamic studies has led to important public humanities projects such as the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Muslim Journeys Bookshelf.

What makes Islamic studies so dynamic? For one, its ever-expanding body of participants, who come from a number of disciplinary perspectives. The field is populated by intellectual networks rather than one identifiable set of intellectual authorities. Islamic studies finds institutional homes not only in religious studies and Near Eastern languages departments, but also in history, anthropology, sociology, political science, ethnomusicology, and art and architecture, among other academic units.

Islamic studies attracts some of the very best scholars in the world. There are now so many scholars producing so much scholarship that it is impossible for one person to know all of the literature in this vast field. Questions about where to do a graduate degree must be followed by the question of what the applicant wishes to study.

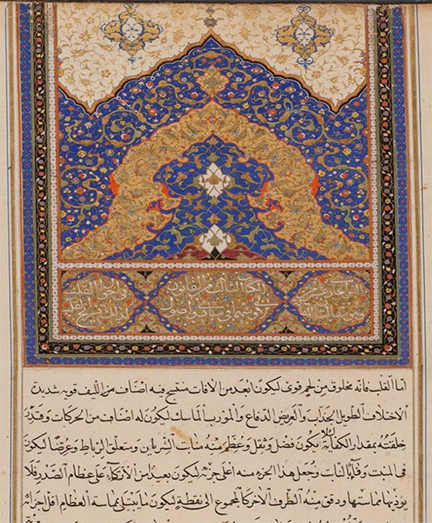

The multi-disciplinary study of Islam nurtures ever-expanding circles of conversation about the significance of Islam to both specialized disciplinary concerns and interdisciplinary inquiry. The origins of Islamic studies may be found in orientalism, that is, the scholarly, philological study of Islamic religion and Muslim cultures. But today, Islamic studies is a field defined by shared and intersecting questions, themes, and data, not any one methodology or set of texts. Its practitioners are not tied together by any one canon—one needn’t be an expert on the Qur’an to be in Islamic studies. Continue reading Ode to Islamic Studies: Its Allure, Its Danger, Its Power