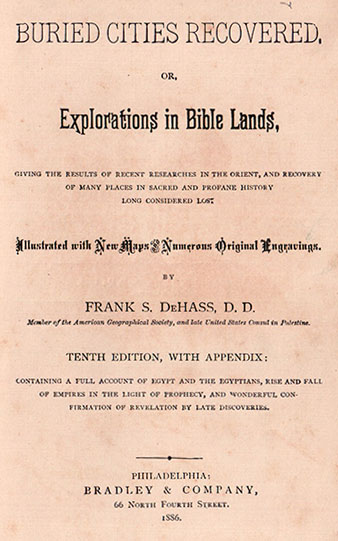

During the 19th century there was a flourishing genre of “Explorations in the Bible Lands.” As the geography and archaeology of the Holy Land came to light, often with only a modicum of scientific investigation, books flooded the market on how the remains and customs in this area were bringing the Bible to life for Protestants in England and America. Despite Mark Twain’s biting satire of the genre in his Innocents Abroad, the Bible Lands books piled on. One of these is Buried Cities Recovered by the Rev. Frank S. DeHass, who was appointed U.S. Consul to Palestine, where he lived for a considerable period. This was first published in 1882 and was in its 10th edition only two years later. The small print at the bottom of the title page says it all: “CONTAINING A FULL ACCOUNT OF EGYPT AND THE EGYPTIANS, RISE AND FALL OF EMPIRES IN THE LIGHT OF PROPHECY, AND WONDERFUL CONFIRMATION OF REVELATION BY LATE DISCOVERIES.” Such was the enthusiasm of Bible enthusiasts of the late 19th century.

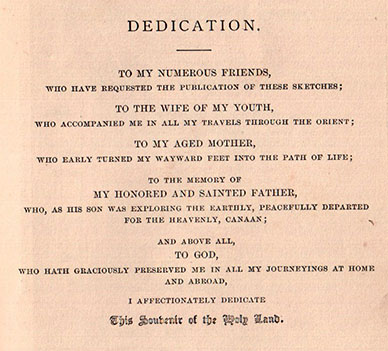

The dedication of the book, reproduced below, is quite flowerly and hardly leaves anyone out, except perhaps the emerging higher critics of the Bible at the time.

to be continued