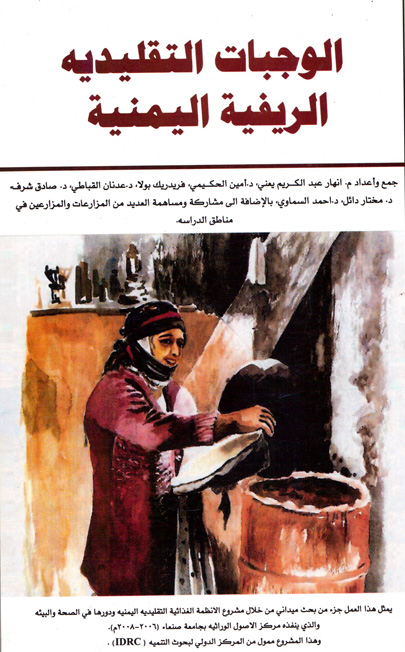

Readers who know Arabic will realize that this blog entry is not about terrorism. Even if you do not know Arabic, what do you think the book cover in the picture above is about? Details coming tomorrow.

to be continued

Readers who know Arabic will realize that this blog entry is not about terrorism. Even if you do not know Arabic, what do you think the book cover in the picture above is about? Details coming tomorrow.

to be continued

Kimball Tobacco Company Factory (1846-1905) in Rochester, New York, published a series of “Dancing Girls of the World.” These appear to be from the late 1880s. Several of these purport to depict women dancing in the Middle East. But it seems the artist had never actually seen ladies of the exotic harem. Take a peek for yourself.

Continue reading Tobacco and Toe Stepping

The Pleiades Conjunction Calendar

One of the indigenous calendars from the Arabian Peninsula is based on the monthly conjunction of the Pleiades with the moon. The moon conjuncts with the Pleiades about once every 27 1/3 days. This conjunction was visible monthly from autumn through spring and occurred about the same time each year; thus it coincided with the main parts of the pastoral cycle on much of the Arabian Peninsula. According to Abû Laylî (in al-Marzûqî 1914:2:199), these conjunctions began at the time of the autumn wasmı rain. This observation is still found among contemporary Sinai Bedouins (Bailey 1974:588). Ibn Qutayba (1956:87) noted that when the moon conjuncts with the Pleiades on the fifth day of the lunar month, winter goes away. The new moon coincides with the Pleiades during the month of Nîsân or April during the naw’ of simâk. This was considered to be one of the most fortunate star movements in the sky, perhaps because of its unique annual character. Shortly thereafter the Pleiades disappears from view at the start of the heat. Continue reading Islamic Folk Astronomy #5

Modern photograph of the Pleiades

The Pleiades in Arab Folklore

The most famous star in Islamic folklore is undoubtedly the Pleiades. Commentators regard the reference in surah al-Najm (#53) of the Quran as the Pleiades; in fact the Arabs often referred to the Pleiades simply as al-najm (the star par excellence), a usage parallel to that in Sumero-Akkadian (Hartner 1965:8). In a well-known tradition, Muhammad links the early summer heliacal rising of the Pleiades with the beginning of the heat, crop pests and illnesses. In another tradition, more political than weather-related, Muhammad is supposed to have told his uncle Abbas (for whom the Abbasid caliphate was later named) that kings would come from his descendants equal to twice the number of stars in the Pleiades. This would imply that Muhammad thought there were 13 stars in the asterism, since the Abbasid caliphs numbered twenty-six (Ibn Mâjid in Tibbetts 1981:84). Continue reading Islamic Folk Astronomy #4

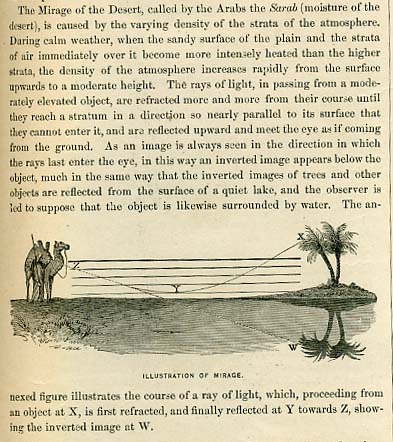

In a previous post I discussed two lithographs from the 1873 edition of Warren’s geography. One of the more fascinating illustrations is one explaining the desert mirage. Here is the discussion and image from the text.

to be continued …

Mohammed at the Kaaba. Miniature from the Ottoman Empire, c. 1595. Source: The Topkapi Museum, Istanbul

Folk Astronomy and Islamic Ritual

Astronomy was relevant to Muslims in large part because of several of the ritual duties proscribed in the Quran and Islamic tradition. The three most important of these are determining the beginning of the fasting month of Ramadân, reckoning the times for the five daily prayers, and determining the proper direction of the qibla or sacred direction toward Mecca. While Muslim astronomers later worked out mathematical solutions to some of these problems, correct timing and orientation could be achieved by those untrained in astronomy and with virtually no computation skills beyond simple arithmetic (King 1985:194). Continue reading Islamic Folk Astronomy #3

Time Reckoning

Era means a definite space of time, reckoned from the beginning of some past year, in which either a prophet, with signs and wonders, and with a proof of his divine mission, was sent, or a great and powerful king rose, or in which a nation perished by a universal destructive deluge, or by a violent earthquake and the sinking of the earth, or a sweeping pestilence, or by intense drought, or in which a change of dynasty or religion took place, or any grand event of the celestial and the famous tellurian miraculous occurrences, which do not happen save at long intervals and at times far distant from each other. Al-Bîrûnî (1879:16)

Time is relative. Given the modern world’s reliance on formalized calendars and machines that define time for us, it is easy to forget that the expansion of Islam occurred at a time when telling time was not dependent on a formal science of astronomy. How time is measured is not only a practical issue but also reflective of the desired interval of duration and the precision in defining it. Simple observation of the sun rising and setting, as well as its location, can easily yield calendars to determining hours, days, months and years. Similarly, the moon’s phases made it a useful measure for the Islamic lunar calendar. Observations of movements by the stars, as well as the planets, also provided practical ways of measuring units of time both short and long. Continue reading Islamic Folk Astronomy #2

from Ibn Balkhi’s manuscript on astronomy, 850 CE

It was He that gave the sun his brightness and the moon her light, ordaining her phases that you may learn to compute the seasons and the years. He created them only to manifest the truth. He makes plain His revelation to men of understanding. Yûnus 10:9 (Dawood 1968:64)

When the Quran was revealed in seventh century Arabia as the basis for Islam, references were made to the sun, moon and stars as evidence of the creative power and practical foresight of God. The idea that God, or a particular god or goddess, had created the visible heavens was not unique. Creating stories about astronomical phenomena is as old as the first civilizations that appeared in the ancient Near East. Some of these survived, in highly edited variants, in the scriptures of Judaism and Christianity. As Muslim science evolved, a variety of religious and scientific knowledge from classical Greek texts, as well as Zoroastrian and Hindu sources, was encountered. While the influence of these classical and textual traditions on Islamic astronomy has been the focus of much previous study on the history of Islamic science, little attention has been paid to the oral folk traditions of peoples who embraced Islam. How ordinary Muslims viewed the same heavens visible to educated scientist or illiterate shepherd is the subject of this chapter. For practical reasons the focus here will be on the Middle East, especially the textual information on the pre-Islamic Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula and contemporary tribal groups in the region.

What is Islamic Folk Astronomy?

It is unfortunate that many times the idea of “folk astronomy†is understood mainly by what it is not. Continue reading Islamic Folk Astronomy #1