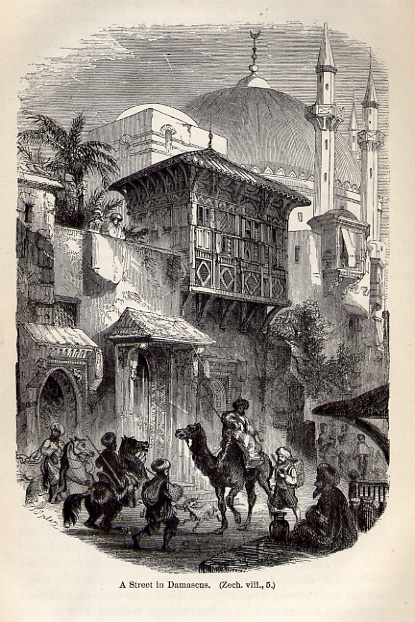

“A Street in Damascus” from Bible Lands by Henry Van-Lennep, 1875, p. 456

Watching vivid color, cable television on an HD screen obscures the art of old black and white movies, which were once able to conjure up fantasies in black, white and shades of gray. Glancing at glossy National Geographic photographs similarly buries further into the archived past all those simple lithographic line drawings storehoused in 19th century travel accounts, Orientalist writings and Bible Custom compendiums. I admire the fruits of progress, but the nostalgia for reaching back into the museum of my book-reading memories demands equal time.

For those who share the tactile thrill of fingers thumbing through brown-edged paper and caressing delicate bindings of century-plus-old books, I dedicate a new theme on Tabsir devoted to the art of lithographic representation of the Middle East. Lithographica Arabica — long live the line drawings and antiquated woodcuts of bibliophilic bliss.

One of my favorite genres for lithographs of the Holy Land is the Bible Custom trope. The archaeological, geographical, missionary and Sunday School touristic appropriation of peoples, cultures and ruins was often illustrated profusely. Consider the long (832 pages) tome of Rev. Henry J. Van-Lennep entitled Bible Lands: Their Modern Customs and Manners Illustrative of Scripture with maps and woodcuts, published by Harper & Brothers in 1875. Like many other bibliolatric enthusiasts of the 19th century, Rev. Van-Lennep looked into the eyes of Palestinian Bedouin and Egyptian peasants and saw Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, David and John the Baptist. Here is the gist of this apologistic voyeurism:

Eighteen hundred years ago the last pages of the Holy Scripture was penned. Since that time the lands of the Bible have passed through various vicissitudes, and been overrun and occupied by many strange nations. Yet it is acknowledged that in no other portion of the globe have tradition, customs, and even modes of thought, been preserved with greater fidelity and tenacity. This is the uniform testimony of all who visit the East… How important, then, to the Biblical scholar is the study of the modern East, not only of its antiquities, intensely interesting as they are, but of the manners and customs of its present inhabitants! The remarkable reproduction of Biblical life in the East of our day is an unanswerable argument for the authenticity of the sacred writings; they could not have been written in any other country, nor by any other people than Orientals…

Let it not be supposed, however, that our object is the mere gratification of a laudable curiosity respecting the interesting countries which have been the scene of Biblical history. We believe the customs of the modern East to be the only key that can unlock the sense of many a valuable text of Scripture and bring it to view. This has been repeatedly proved by experience, and a more thorough acquaintance with the East will doubtless multiply these valuable interpretations.

More than a century and a quarter later, the “modern” customs described seem as distant as the Biblical narratives themselves. A contemporary Bible preacher visiting Gaza would hardly find Samson or Delilah in the vineyards, but perhaps the ongoing strife between Hamas and the IDF would conjure up visions of Joshua at the Battle of Ai. Sentiments — theological or otherwise — aside, the illustrations remain, combining the panopticon belief of the devout with the stereopticon patina of an art form virtually abandoned. Old dogmas never quite die, especially given the fervor of Protestant devotion to the Word not in the flesh; old photos never fail to delight the eyes. So let the logical part of your brain take a rest and the contemplative side feast on the power of an image you must read between the black-and-white lines.

If anyone would like to contribute a lithograph, woodcut or illustration from a 19th century or earlier text, please send this to the webshaykh.

Daniel Martin Varisco