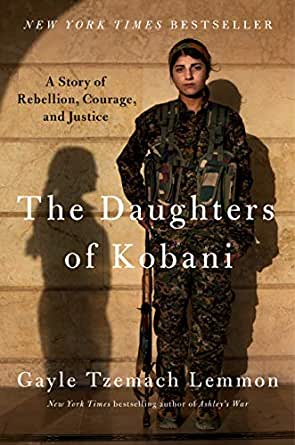

I recently finished reading a fascinating and well-informed account of the role of female Kurdish fighters during the last decade in the fight against the Islamic State (ISIS) in northeastern Syria. This is The Daughters of Kobani by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon. Based on interviews with many individuals involved in the fighting, especially several of the major fighters, a powerful story is woven in a narrative that I find riveting at times. The fighters she describes are genuine heroines, young girls who rose to the occasion. Many of them gave their lives, others were tortured and abused when captured. There is a sub-story here as well, the realization of the horror unleashed by ISIS, including the many Western recruits for whom rape and murder were seen as a right. For Kurds, Yezidis and anyone who did not succumb to the terror-laden evil of ISIS, this was hell on earth.

The history of the region now known as the Middle East and previously styled the Biblical World or the Orient has seen the destruction of many people from the earliest recorded history. Those who believe in the stories of Adam and Eve will remember that Cain, one of the first couple’s two first-born sons killed Abel, his brother. As the story goes, the dispute was over religion because Cain was jealous that God preferred the animal sacrifice of Abel the herder rather than his own vegetable sacrifice as a farmer. But reading behind even these poetic lines the real issue here is about the shedding of blood. The rest of the Bible, Old and New Testaments, is a bloody book with God killing off the whole earth and even its animals with a flood, with the Children of Israel ordered by God to kill Canaanites without mercy, with Assyrians, Babylonians and Romans adding to the overall death toll.

When Islam superceded Judaism and Christianity in much of the region, the killing did not stop because human nature did not change. In truth the many reasons why humans kill each other are only superficially about religion, which is simply used as a justification. On a group level we call the desire to exterminate another group of people “ethnic cleansing” or “genocide.” Beyond this is the attempt to destroy a people’s culture and language. As White Americans flooded into the American West, the natives were either killed, put in reservations or forced to “assimilate” by conversion to Christianity and the White Man’s (and White Women’s as well) ways. The colonial expansion worldwide was almost always one resulting in cultural genocide. When Ataturk rebuilt the idea of Turkey as a modern state out of the ruined Ottoman hopes of World War I, the variety of ethnic groups in this state were redefined as “ethnic Turks.”

One of the longest lasting ethnic groups, saved from extinction in large part because of the highland enclave most have lived in, is the Kurds. Spread out geographically between modern Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, all of these states have marginalized, persecuted and at times indiscriminately killed members of their Kurdish population. But the Kurds have survived, most recently establishing a quasi-homeland in northern Iraq following the fall of Saddam Hussein. To the extent that Kurdish issues make the world news, most recent discussion has been about the Kurdish fighters, who with outside support were able to wrest control of parts of northeastern Syria that had been overrun by the Islamic State (ISIS) less than a decade ago.

Among the Kurdish fighters were a number of women who took up arms and learned the manly art of war firsthand. This has been widely covered in the media, in part because of the common stereotype that women in the region are stay-at-home pawns of a region-wide patriarchal system that denies them rights. Admittedly, the number of women who are in the military or a local militia throughout the region are few, but when push comes to shove the Kurdish case shows that women are, and indeed have been (as can be seen below), fully capable of fighting for a just cause.

The unanswerable question after reading this book is what the future holds not only for Kurdish women, but for young girls and women throughout the region. The burden of sexism is a worldwide phenomenon that has gained more attention as the world becomes more globalized. Attention, however, demands action beyond the passing of laws that are not followed and ideals that are not approved. Due to this burden it is often forgotten that talking about women’s rights should also involve taking about human rights. Women are not a separate species, nor can achievement of equality ever be achieved without men realizing and advocating for that equality. Nor is the idea of equality the sterile notion of “sameness” any more than cultures having to all be the same. For Kurdish women the future is not just about their rights as women, but what it means to freely live as Kurds. The daughters of Kobani have opened a door; it is up to the sons of Kobani not to close it but keep it open for all.