I wonder if the judges who dole out the increasingly meaningless Nobel Peace Prize ever have second or third thoughts. In 2011 the Yemeni journalist Tawakkul Karman shared the prize for her visible opposition to the regime of Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Salih. The prize is symbolic to be sure, so it is not surprising that a recipient becomes hyperbolic with the international public attention. Karman was picked because of her advocacy work in Yemen, not because she was a savy expert on Middle East politics. A week ago she decided to cash in on her reputation and lend support to the sit-in followers of deposed President Morsi. The Egyptian authorities, not unsurprisingly, denied her entry for an obvious propaganda tour for the Muslim Brotherhood. Karman is shocked, it seems, that a military regime that would oust a sitting president would then deny her entry to come into Cairo and provide support for the opposition.

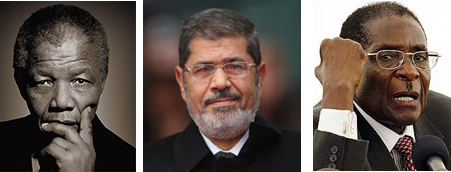

Foreign Policy has posted a commentary by Karman entitled Morsy Is the Arab World’s Mandela, with the subtitle Why we must stand and support the Muslim Brotherhood’s fight for democracy. Nelson Mandela? At a time when this fellow recipient of the Peace Prize (in 1993) is rumored to be near death’s door, this is an insult to the work of Mandela to end South Africa’s apartheid. My point is not to vilify or defend Morsi, but to compare him to Mandela is pure media hype. Mandela represented the aspirations of a diverse group that happened to have non-white skin and that had been victimized by a racist white apartheid. Mandela appealed to the basic humanity of his fellow citizens, not to a particular religious sect. When he came to power, he did not try to push through legislation that would turn the tables and discriminate against the former white residents. He is recognized as a statesman because he did not grovel in partisan politics.

Karman expressed sympathy with those supporters of Morsi who have been killed and persecuted in the recent coup. She is right to point out such crimes, but it is naive to assume that the Muslim Brotherhood is a peaceful political organization with no agenda to discriminate against fellow Muslims who differ or for Copts and Jews. She ends her commentary by saying: “There are limited options for those of us who care about Egypt’s future: We can either side with civil values and democracy, or with military rule, tyranny, and coercion.” Yes, the options are limited, but they are not black and white, which only paints the future into a binary cul-de-sac. The Muslim Brotherhood, by its own admission, history and actions during the first year of Morsi’s presidency, does not side with civil values. Ask any Copt about their civility? Ask the millions of Egyptian Muslims who took to the streets and gave an excuse for the military to step in. Consider that the Egyptian military, for all its faults, is still more popular in Egypt than the Brotherhood.

The debate over the removal of Morsi centers around an idealized notion of “democracy” that an election process which is never pure automatically represents the “will of the people.” First of all, there is never a unified “will” but rather a range of views. Those who “win” elections do so by political means, forming temporary alliances, promoting propaganda and relying on the prejudices and ignorance of many, if not most, voters. The “winner” of an election is in many cases the lesser of two evils, victorious more for who people are voting against. Egyptians voted against a candidate tied to the old Mubarak regime as much as out of desire to have Ibrahim Morsi as their president. The same is true in many, if not most, democracies.

Rather than Mandela, a case may be made that Morsi is the Arab World’s wannabe Mugabe, who last week defied the pundits and “won” yet another election in Zimbabwe. The difference is that Mugabe came from the military, while Morsi came from an ideological sect.