First, it was the fall of Mubarak; now comes the second act: the pending removal of President Morsi, who has managed to do more damage to the image of the Muslim Brotherhood than Nasser, Sadat or Mubarak could. The people massed peacefully in Cairo’s Tahrir Square have had enough of a candidate who pretended to be independent but over the past year has increasingly been linked to the intolerant policies of the Brotherhood. Five ministers in Morsi’s cabinet have resigned, including the Tourism Minister Hisham Zaazou, who was furious that a man linked to the tourist massacre in Luxor in 1997 that killed 62 people had been appointed as a governor in Luxor. The announcement by the army giving Morsi an ultimatum to satisfy the demands of the protesters has all but assured that he will not survive. A formal coup in unlikely, but the pressure on Morsi to resign may do the trick.

The major concern in Egypt is not about democracy but the economy, which has crashed with little prospect for recovery under Morsi. The continuing unrest, coupled with fear of the rising influence of the Muslim Brotherhood, has decimated the tourism industry, which is a major impact on the local economy. In 2008 almost 13 million tourists visited Egypt, bringing in some $11 billion to the Egyptian economy. Today hotels are near empty and tourism is virtually non existent. Conflict at the luxury Semiramis Hotel in Cairo in March caused many tour operators to cancel bookings there. When the tear gas settles, the Pyramids will still dot the horizon in Gizeh, but in all likelihood Morsi will be out of a job soon.

Egypt is awash with more than the annual floods of the Nile, meager as they have become since the building of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s. The population has swelled to over 85 million, the 15th largest country in the world. Half of this number is under the age of 24 and the chances of most of these young people finding meaningful jobs as they grow up are dim. For several decades Egypt has survived as a remittance economy, with Egyptians working abroad sending home cash to their families. But there are fewer opportunities for work in other parts of the region, creating more pressure on the job market at home. With tourism in decline, a broad sweep of the work force is suffering.

Many Western pundits feared that the fall of Mubarak would usher in an Islamic republic, especially after the election of Morsi. Tensions have risen between the most conservative Muslims and Egypt’s minority of Copts. But Egypt is not Iran; most Egyptians practice a faith of tolerance, a survival tactic for the many invasions and political upheavals in the country’s Islamic history. The scale of the protests indicates the level of frustration of Egyptians across classes. As in the fall of Mubarak, the key player remains the military. They sided against Mubarak, probably aided the election of Morsi and now once again are seen as fostering the path to a better future.

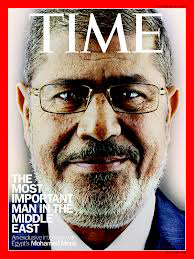

Is there hope for Egypt? The longevity of the pyramids suggests that there is something in the Egyptian psyche that is rock hard. This land is no stranger to conflict. It has vast potential in its heritage for tourism, but the transition from a peasant agricultural society to a wannabe industrial haven has not worked very well. Unless the population growth is curbed, the economic future will continue to be fragile. Whoever replaces Morsi will still face the same problems that have brought the masses into the streets. But perhaps by not having a partisan religious collar hanging around his neck, the next leader will last more than a year, army permitting. Time Magazine was wrong; Morsi is not really the most important man in the Middle East after all.

Daniel Martin Varisco