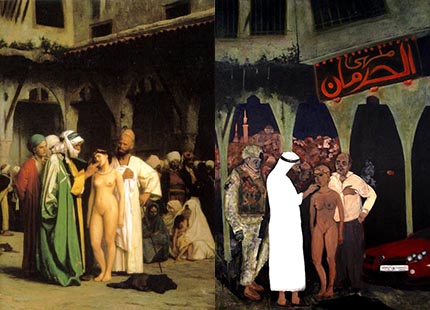

Gérôme’s “The Slave Market,” left; Inanna in Damascus by Sundus Abdul Hadi, Iraqi artist, right

Before Edward Said revitalized the term “Orientalism” in his seminal 1978 book of the same title, the major use of the term was for a genre of Western art, centering on exotic depictions of an imagined or at least embellished beyond the real “Orient.” The Gérôme painting of “The Snake Charmer” of the paperback version perfectly captured the prejudicial element that Said rightly exposed in much of the literature and academic writing about the Middle East and Islam. Such a biased representation cannot be glossed as mere “art for art’s sake,” if indeed art is ever really only for “art’s sake.” I recently came across a painting by Sundus Abdul Hadi, an Iraqi female artist, that responds aesthetically to another famous Orientalist painting by Gérôme; these are the two images juxtaposed above. There is nothing inaccurate in either painting. Selling female slaves was a lucrative trade throughout the Islamic era and current sexcapades by wealthy Arab sheikhs are well known.

The response painting is a brilliant counter to Gérôme. Both highlight the exploitation of women as sex slaves, either in the older legal and literal sense or the modern illegal but still practiced nonsense. It is possible to look at either picture and focus on the naked body of a woman on display. This is the voyeur’s gaze, which is often the prime motive for creating as well as viewing such a work of art. But when placed side by side with the modern response painting, the very fact that the woman is still only an object for purchase overrides a one-directional voyeurism. This is not simply a scene of the imagination, but a reality that has outlived the 19th century Orientalist genre and indeed is hardly unique to a genre exposing the bodies of Oriental women.

The Gérôme painting might be considered “art for art’s sake” in that it obviously was not meant to draw attention to the plight of women sold as sex slaves. But its reception has not been confined to an abstract aesthetic, which is why it fits so well with Said’s message. The response painting uses an art form to make a statement about the objectification of women. It transcends and in a sense strips away the aesthetic pretense of Gérôme. This is no longer a gaze from without, but a view from inside looking in. Both paintings focus on the exploitation of the female as a sex object, but the second painting unpacks the first, upstaging the blatant othering of Gérôme for a more basic and timeless message: exposing the female body is more than appears on a canvas to the Western voyeur. Sexism is not Oriental, it is universal. The background may change over a century, but it is the male that still enslaves the female for her body, no matter where the painting might be made. It takes courage to stand naked and expose this inequity; only the second painting has this courage.

Note: My thanks to Juan Caraballo-Resto for sending me the name of the artist.