Last Thursday was dubbed “Topless Jihad Day,” a call by the feminist group FEMEN for women to protest in support of a Tunisian woman who posted photographs of herself topless (with remarks on her body that many would consider tasteless) on her Facebook site and soon received condemnation and calls for punishment. The result was hardly an outpouring of indigenous support like the “Arab Spring” that flooded the main squares of Tunis, Cairo and Sanaa. The FEMEN website has posted images of women baring their breasts in Rio de Janeiro, San Francisco, Montreal, Paris, Milan, Kiev, Brussels, Berlin and a few other major cities. Two things stand out about this day of protest. First, it takes place only in cosmopolitan Western cities, not in Muslim-majority countries. Second, several of the scenes focus on the protesting women being arrested for breaking the law. The patriarchy that is being protested is not, therefore, only an issue about Islam.

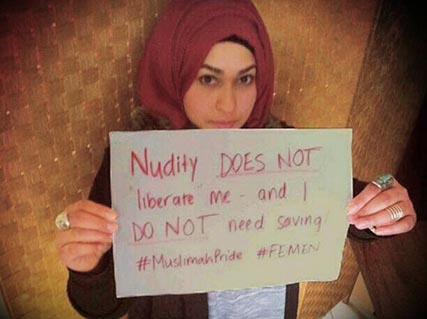

There is a basic principle of physics that every action results in a reaction. The moral code that would cause a Tunisian cleric to condemn a young Tunisian woman for exposing her breast on Facebook causes a protest from an international feminist organization. And, not surprisingly, there is a counter to this from a “Muslimah Pride” network. As the young woman in the image above indicates, she does not feel liberated by exposing her body. But perhaps even more poignant is her comment that she does not need saving. It is not clear if this Muslim woman is condemning the Tunisian woman at the center of the current protest, but she is definitely making a statement about her own body. Whose body is it anyway?

FEMEN has attracted followers for a variety of reasons. I suspect that some testosterone-loaded males in the West cheer wildly whenever a woman shows her bare breasts. These hardly support the stated goal of FEMEN: “sextremism serving to protect women’s rights, democracy watchdogs attacking patriarchy, in all its forms: the dictatorship, the church, the sex industry.” Historically there is no question that women have not had equal rights with men in economic, political or legal contexts; this is true for almost all cultures, ranging from those with despicable patriarchal rules to democracies with permanent glass ceilings. Secularism has challenged many (but not all) of these inequalities, giving women the right to own property, vote, and theoretically have equal opportunities in education and the workplace. Appeals to women’s rights resonate with most people, whether secular or religious, but the devil is in the details.

There is also an elephant in the room, in everyone’s room: who decides what women’s rights are? The major monotheisms subscribe to sacred texts that define gender relations and often provide specific guidelines and prohibitions. Judaism, Christianity and Islam all condemn adultery, for example. But neither the Torah nor the New Testament nor the Quran dictate a specific fashion of clothing for all time. Historical evidence suggests there have been times in the history of all three religions when women were not humiliated or punished for showing a breast. There is good reason to believe that the sexual objectification of the female breast is a rather modern ideological measure, certainly in the long evolutionary trek of our species.

So who decides what parts of a woman’s or a man’s body must be covered, in public or in private? All societies have rules of propriety that relate to exposure of the body. There is hardly a society that does not adorn the body in some way by painting, tattoos or adding some object through the skin or that does not alter the natural body in some way. The human body is the most significant canvas for social identity, unclothed or clothed, as fashion designers know so well for the latter case. It is also a powerful symbol in all religions. Abraham was told to circumcize his children as a sign of the covenant with God; the blood-soaked body of Christ on the cross and stigmata of St. Francis power the emotions in Christianity; the severed head of Hussayn inspires shi’a Muslims to draw out their own blood in remembrance. In addition to the mundane rules about what you can expose and what you should cover, the body itself remains a vital symbol within all religions.

As Rousseau wisecracked just a few centuries ago, we are born into this world free, but everywhere we are in chains. These chains are the rules which are imposed to govern behavior, although not all are shackles of iron that draw blood. But rules change because rules are constantly debated. As Margaret Mead reported for Samoa in the 1920s, a brother and sister near the age of puberty were not even allowed to eat together. Yet girls traditionally went around in this warm climate with breasts exposed. Under the influence of Christian missionaries, however, women were forced to cover their bosoms. Wherever Victorian Christian missionaries went, the natives were told they needed to cover up. Ironically, it seems that the spread of Islam by da’wa of Sufis into Asia and Africa several centuries ago did not dictate covering the breast, because it was not a cultural taboo.

Personally, I am a firm believer that women’s rights need to be decided by women, not dictated by men. I have walked through enough art museum galleries to appreciate the beauty of the human body; I have seen historical images from the ancient world to know that an exposed breast need not be tagged as an invitation for lust and male conquest. To me it is sufficient to say “Whose body is it anyway?” But the question then becomes whether or not some women with strong beliefs about how their body should be presented have the right to force others to do the same. If patriarchy is wrong because it allows a woman no choice of her own, then the issue is really about being forced. By this logic, it is also a problem to force women to rebel against a system they do not personally see as taking away their rights. I do not wish to box myself into the no-exit corner of extreme cultural relativism. But choosing to wear a veil or a particular item of clothing that does not cause physical harm or create a problem for others (I would not want a woman in full niqab to be driving a car in that garb anymore than a man in an iron mask) should be left up to a woman herself.

But I am not the one who makes the rules in Tunisia or anywhere else, even in my own society. As a man I cannot unilaterally decide I am hot, remove my pants and prance around unclothed in liberal New York. Rousseau’s social contract curbs any personal desires I might have, given the need to abide by what society perceives as the rules of common decency. And social contracts vary across cultures. To the extent a Tunisian woman feels trapped by the strictures of the social contract in her own society, as an outsider I cannot change that contract. I may sympathize with her as a fellow human being, but I am not convinced that change can ever happen from the outside. If the problem is a patriarchy that does not allow women freedom of choice, the change really needs to come from the men that support such a system, even if women are said to collude in what I clearly see as male domination. So would most Muslim men in Tunisia or Egypt or Yemen look at these FEMEN images of women baring their beasts in public and writing the f-word on their bosoms as an incentive to let their women do the same or would it further entrench the prevailing attitude of many Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa that Muslim women need to be protected from the lack of morals in the West? As much as I would like to see a world in which an individual could walk naked and not be the object of sexual harassment or abuse, I do not have a clear-cut idea on how to move closer to such a utopia.

Whose body is it? My own is my own, although I do not really own it in a way that I can do whatever I please. Your body is your own, no matter what I do with my own or what a woman in Paris does with hers. Don’t worry about those FEMEN protesters in the media; only you can remove your veil and it is your choice. I, for one, can survive without seeing your breast.

For a related commentary on the issue, please see my “Middle East Muddle” blog on Anthropology News. Comments welcome from all.