Image source: alhadath.yemen

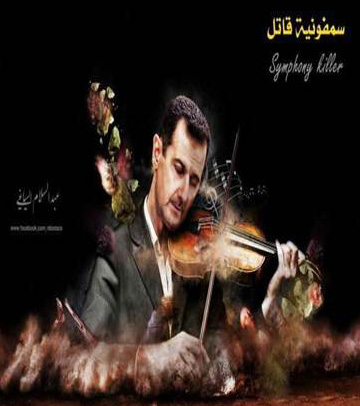

The demise of Bashar al-Assad continues its downward spiral with bodies strewn all over Syria in the process. What makes him hang on? Can he not see what just about every pundit outside of Syria and increasingly most Syrians see in blood red letters: mene mene tekel upharsin? Even vain Belzhazzar saw the gig was up in Babylon when those lines cracked his banquet hall. Or is he raving mad in the style of Nero, who plucked his lyre while Rome burned? Or is he just a chicken without a head, but who is still trying to bury his head in the sand?

He hangs on for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, because for the time being he can. Russia has not yet told him he has to go and the United States has basically given him leave to do whatever he wants to his own people except gas them. The military has not yet deserted him in sufficient numbers and they are, thanks to Russia, very well armed. Even the hint from the U.N. envoy Lakhdar Brahimi that Assad has been in power long enough is not likely to move the last of the pre-Arab-Spring dictators (not counting kings, sultans and emirs for life) into retirement.

The Syria of 2013 is not that conquered by Umar ibn al-Khattab, not that of Ayyubid Saladin, nor that run over by the Mongols, nor that ruled briefly at the end of World War I by Faisal of Arabia (patron of Lawrence of Arabia and vice versa), nor that which joined the ill-fated United Arab Republic initiated by Gamal Abd al-Nasser in the 1960s. But there are indeed historically-stretched fault lines. As was learned the hard way in Iraq and Afghanistan, old fault lines break into hardline violence only too easily. Syria remains, despite four decades of Ba’ath dictatorship, a melting pot that never quite melded.

The major fault line, sharpened during the French mandate, is the Alawite (a.k.a Nusayri) sect. As a disliked shi’a splinter group in a sunni sea, the Alawites had few friends and remained poor cousins. Until the end of World War I they were so disdained that they were not even allowed to testify as equals in a court of law. But this changed under the French mandate, when a separate Alawite region was established and the fierceness of the Alawite fighters was coopted into the French security forces. After Syrian independence, following World War II the rise of the Ba’ath party facilitated the coming to power of Hafez al-Assad in a military coup. As a member of the much despised Alawite sect, although hardly a religious icon, al-Assad was tolerated (without much choice) but never really accepted by the sunni majority.

Syria still has a viable Christian population, perhaps as many as 10% of the population before the violence, as well as other minority groups such as Kurds and Armenians. At the start of the current protests, al-Assad was seen by many of these minorities as a buffer against the formation of a conservative sunni Islamic state. But all buffer bets are off as the Assad regime is boxed into one corner after another, losing military bases and total control of the borders. Still, his government has billions of dollars to waste in the process of trying to hang on.

And the deaths go on: some 60,000 in the past two years according to the United Nations. That is a ration of about 1/350 people in Syria. If that same ratio of death happened in the United States, our death toll would be 891,000 for a period less than two years. But this death toll seems less newsworthy than fiscal cliff chatter, the endless round of college football bowls, and which films have been nominated for the Oscars. Shame on us for not paying more attention to the sham of state-sponsored murder and widespread civilian mayhem now running amuck in al-Sham.