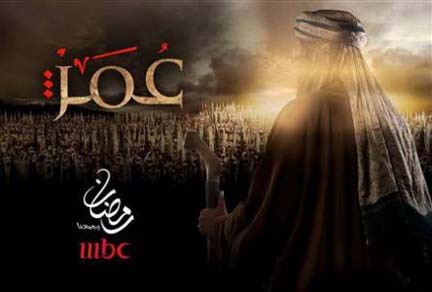

As Ramadan for the Hijri year 1433 draws to a close, the violence between Muslims on the ground is paralleled by the violence about Muslims on the screen. The daily slaughter of Syrians, continued terrorist bombings throughout the region and the uncivil rebellion in Mali dominate the news, as such atrocities should. But cinema does not lag far behind in showing blood spurting out of bodies and broken bones, all in the name of politicized religion. I am not talking about The Expendables, where aging Hollywood superheroes unite to make themselves even more money, but a Ramadan television serial that has captured the attention of Muslims across the Middle East: a retelling of the story of the second caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab. Click here for the trailer and here to watch Episode #2.

Premiering 36 years after Moustafa Akkad’s acclaimed The Message recreated the life of Muhammad without actually showing Muhammad, the serial ‘Umar in 30 episodes is a millions-of-megabucks production worthy of Cecil B. DeMille. The earlier film had the blessing of the major Islamic organizations, since it avoided showing an image of the prophet Muhammad. It was a bit eerie to see Anthony Quinn as Hamza constantly speaking to the camera as though the camera-not-very-obscura was in fact the Prophet. But this new film has been railed against by the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia and the sheikhs of al-Azhar because it dares to show an actor playing a companion of the Prophet, notably the caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab. If it had been Saladin, that would be okay it seems.

The film itself has a broad Gulf context, funded by the private Saudi MBC Group (based in Dubai) and state-owned Qatar TV. Once again the Al Jazeera connection has raised eyebrows across the jazeera. Reuters has published a variety of condemnations, including a statement by Dubai’s grand mufti: “The Guided Caliphs were promised the heavens … Their lives cannot be depicted by some actor,” Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed, Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates tweeted his reaction: “I will not watch the Omar Ibn al-Khattab series.” But I suspect that the majority of Arabic-speaking Muslims will.

The film also has its defenders, many of whom are delighted to see a high-quality production that brings the formative period of Islam to light in such an engaging way. Those who argue against this kind of film are on the losing side of history, especially when a minister tweets to the world that he will not watch it. First, films like this make money; otherwise they would not be made. This is not a film to convert non-Muslims, but to entertain Muslims or anyone who understands Arabic. Second, film has come to dominate all of our lives and our modern-day visual addiction to the screen cannot be denied because of an age-old directive meant to distinguish the early Muslims from the icon-loving Christian communities.

Films like this are attacked because they allow for a rethinking of sacred history. Some films, like the Hollywood family fare The Bible, are so lame that they might as well belong to the Dr. Doolittle series. Hollywood has a long love affair with Bible stories, including monumental blockbusters such as The Ten Commandments, but also a fair share of cheesy quasi-sex flicks like Sodom & Gomorrah. The number of Jesus films is legion, so to speak, but eventually there would be a film like the bloodcurdling The Passion to rewrite the theme of The King of Kings.

Negative reactions to the film stifle the kind of rethinking that always goes on in religious systems. Both Judaism and Christianity have survived, with Hume’s help, the idea that myth can be construed as history and that miracles can be made to sound scientific. Muslims will increasingly face this same issue with increased education and the inevitable global consumption roller coaster that is driving past what was once called “modernity.” Must any religion hold on to what would be considered myth outside of that religion, as though ethics and spiritual guidance must be held captive to the miraculous? Is it not vain hubris to assume that one can Whiggishly recreate history for a period in which there is no actual historical evidence? Are we really destined to choose between competing visions of a day of judgment when the “others” get branded as infidels and cast into the fire and only a select few merit the attention of a God assumed to intervene mercifully in history? These are the kinds of questions that films (although not this one, which is quite standard sacred history) can engender and this is why the old guard hates them (the films and the probing questions).

But I suspect next Ramadan another caliph will be on the screen. No matter how many sermons will attack it, the cinematic viewing of Islam’s history will hold fast.

Daniel Martin Varisco