Sailing Seasons in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean:

The View from Rasulid (13th-14th Centuries) Aden

by Daniel Martin Varisco

[This is a lecture presented at the Red Sea Trade and Travel Study Day of the Society for Arabian Studies at the British Museum, October 5, 2002, and subsequently published in Yemen Update. For Part 1, click here; for Part 2, click here.]

Thursday, 15 Sha‘ban, 691, August 1, 1292

We are now but a day’s sail away from safe haven in Aden, if God wills and the wind does not cease to obey his commands. It has been a good journey thus far. No major storms or pirates, though we did see a shipwreck on the reefs south of the Farasan Islands. Our pilot, praise God, knows his way over the shoals, even if blindfolded, I think. In the morning we took aboard some fresh water at al-‘Ara, after coursing around the tip at Bab al-Mandab and leaving Bahr al-Qulzum. After my noon prayer, when the sun beat down so mercilessly and I was sorely tempted to jump into the water with all my clothes on, I suddenly remembered that this was the midpoint of Sha‘ban with only two weeks left until the holy fasting month. Today is the anniversary of the day the Prophet, peace be upon him, was instructed to make Mecca the qibla rather than Jerusalem. God willing, I will make the pilgrimage in the coming year. Even thinking of the well of Zamzam made the warm water in the fantash all the more sweeter.

As night fell, I remembered an earlier trip, when a tormenting monsoon tore our sail and nearly capsized the ship as we departed Zayla‘ for Bab al-Mandab. These were the ‘awasif winds, fouling us with the stench that only Iblis breaking wind could send. That turning point is a dangerous point. An old sailor on board, who has often traveled along the African coast from Mogadishu, told me that only ships like our jalba can make the passage safely; no boat with iron nails could sail past, for God, our Protector, has ordained a magnetic mountain to attract hand-wrought nails and split an intruding vessel asunder. But only the infidel Christians defy nature with such innovations. May God protect the holy cities from the ravenous appetites of crusader cannibals.

How frail this ship must seem to the Lord of the sea and land. To me, a mere mortal, it is a marvel that the long stern and sharp bow of our dhow beckon the wind to bellows the triangular lateen sail, like a smith forging iron. Thus does God’s creation assist us, when we are faithful. Framed with teak and a few planks of coconut, our vessel glides along the surface of the sea with only palm fiber daubed in fish oil as a lifeline between us and the lot of Pharaoh’s army. I sat today beneath the mast, towering over me a good 30 hand cubits, a visible reminder that the works of our hands can only point to heaven, never attain it by stealth or wealth.

Saturday, 17 Sha‘ban, 691 (August 3, 1292)

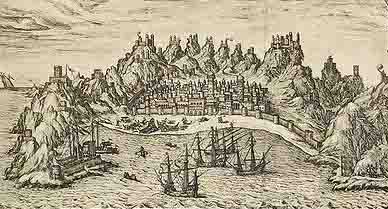

Praise God, the all-comforting, yesterday I arrived safe and sound and am staying with ‘Ali Yusuf, a local broker (dallal) with long ties to the Karimi syndicate. The trip here was not half so demanding as the mindless meddling of the port authorities, who treated us as though we were common traders or thieves rather than respectable businessmen. First, the harbor officials (mubashshirun) arrived alongside in their small sanbaqs, as we headed to anchorage in the lee of Sira Island. Had it been winter, with the northeast monsoon swells in full blow, our mooring would have been untenable here and we would have tacked to the southern side of Sira to unload our wares on the lighter boats. The chief official welcomed us in an officious way, speaking to our captain as though he were a some mangy Mamluk to be barked at. It helped that our clerk or karrani was well prepared, as was usually the case on major trading ships, and handed over the list of crew members and passengers, as well as an account of all the merchandise in the hold. It was not until this oaf of a port official realized we bore a special gift for the sultan himself that his tone changed. Immediately he dashed off to tell the governor, since the gift was a “robe of honor,†an embroidered silk shirt actually worn by the Sultan Khalil, truly a present to be protected in this port of petty thieves. The governor sent four soldiers, who took the package to the government storehouse for safe keeping. Messengers were to be sent the next day to inform the Sultan al-Muzaffar, who was in his garden villa at Tha‘bat, and rumor has it that he is not in the best health. May God preserve his soul, considering the amount of money he has borrowed from my masters.

After dropping anchor, we were anxious to go ashore, but there were many formalities to endure. The inspector arrived, a fastidiously dressed man in basic white cotton, much the worse for wear and potted with sweat stains, which he strutted as though it was the finest silk lanis. He had doused so much rose water on his beard that I was afraid the bees would come from as far as Daw‘an to draw nector, and what tasteless honey that would be. He felt through the most intimate parts of our clothing with a probing hand of gnarled, spindly fingers as though one of us had purposefully hidden away a pearl of great price. Had he stuck his thumb into my mouth, no doubt he would have recorded my gold filling as customs due. But there was nothing to find, for we are all honest, God-fearing men, even the poorest sailor on board. To his undisguised dissatisfaction, I and two other traveling merchants were given permission to leave the ship the next morning, a light skiff to be sent expressly for that purpose. Immediately, another verse from surat Yunis came to mind:

Allah replied: ‘Your prayer is heard. Follow the right path and do not walk in the footsteps of ignorant men.’

As this portly fellow descended, complaining all the while, into his small boat, I felt relieved not to have to follow in his steps. After so many days at sea, I was glad to return again to solid earth, but waterless Aden is no Eden.

to be continued