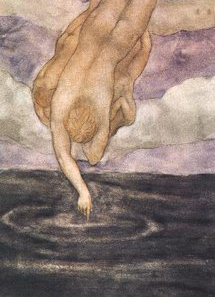

Art by Khalil Gibran

by George Nicolas El-Hage, Ph.D.

From my book: The Return of the Hero and the Resurrection of the City, originally written in Arabic and translated by George N. El-Hage and edited by MaryAnn Del Vecchio, Ph.D.

Forward

These four letters, selected out of ten, are in fact a personal account of my feelings as a father, an immigrant, and a poet, towards my son. They are an emotional register of the dilemma of alienation, exile and loneliness that faces every immigrant, Lebanese or not, who, for various circumstances, leaves his or her country and emigrates abroad. I happen to be a Lebanese man who traveled to America during the Lebanese war to continue my education and make a future for me, my parents and my siblings. Like many cultures, being the eldest son in a Lebanese family carries a huge responsibility that falls on your shoulders and becomes your cause.

America, as it was known, was “the land of endless opportunities, the generous and welcoming land, where money grows on trees,†and “attaining the American Dream was only a measure of your determination, perseverance and hard work.†Indeed, this is the land where endless possibilities abound and the reality of forging a better life has, and still does, lure people from around the world. In fact, may God bless America.

It was not an easy task to write these letters to my son and to put my innermost feelings out there in the open. But as a poet, it is my mission to share because poetry is the art of the unusual encounter with the inevitable and the holy, and the poet’s mission is to always take the road rarely traveled and to return and inform fellow beings.

The complexity of emotions displayed in these letters is further heightened as the text becomes a living document and evolves into a persona by itself and onto itself. The words, charged with meaning and burdened with symbolism, oscillate between two languages that individually struggle to claim the message, each for itself, and to embody the meaning, which although universal, is yet very personal. In many instances, the meaning is loaded with implications particular to its own culture and telling of its peculiarities and symbols, for language is an expression of culture. The text assumes a higher intensity and urgency when the private is projected onto a national and patriotic level and when the intended symbol is yet elevated to transcend the limitations of expressing the anguish, not only of the individual, but of the many, and becomes imbued with the mythical, the historical and the sacred.

Language is an amazing tool, and words are the body that crystallizes the ethereality of emotion in its material form through ink and paper. Although words attempt to move in a parallel and fluid motion, carrying meanings across languages, nevertheless, words remain locked into their own culture by virtue of their symbols. For this reason, translation of poetry between two different languages, from the mother tongue to a foreign tongue, and with two diverse alphabets, poses at times insurmountable challenges.

A perfect example is the name “Nicolas†in English versus “نقولا†in Arabic. When each letter of the name in Arabic is used as a symbol, the two languages collide, and each retains its individual identity associated with its own culture and symbolism. For the readers familiar with Arabic, the passage below illustrates the difficulty in translating the name. Since the sentences intimately relate to each letter in Arabic in the spelling of the name, “Nicolas,†the text is impossible to translate into English and still retain its original meaning. In Arabic, every letter becomes a symbol that recalls a word or a source that begins with the same letter from the historical, the mythical and the sacred. In English, there is no such equivalent.

“N I C O L A S†– “ن Ù‚ Ùˆ Ù„ ا†”

نونك من نور الله, من نجمة الصبØ, ونسمة الØقل ونغمة الغسق. قاÙÙƒ من قربان الآلهة, من قرآن Ù…Øمد وقواÙÙ„ العائدين. واوك من ومضة سي٠إيليا, وعلي والاسكندر وطارق ÙˆÙخر الدين. لامك من لبنان سنا Ù‹, من لهÙتي ولهيب شوقي وليلة القدر. ألÙÙƒ من إنجيل Ø§Ù„Ù…Ø³ÙŠØ ÙˆØ§Ù†Ø´ÙˆØ¯Ø© الأناشيد واساطير الغابرين.

When I wrote the first letter published here, my son was three years old. Hence, the feelings, emotions and thoughts are, in fact, a portrayal of my own struggle, frustration and fight. He had nothing to do with my strife and definitely did not experience any of this suffering and loneliness. This is my acknowledgement that I have projected my own fears on him while he remains innocent of this burden. This was my epic to survive, my cross to carry and my battle to endure. These letters are a private record, a personal portrayal of my inner struggle. I put it out there in hopes that it may mirror the experience of many other immigrants and highlight their attachment to their first born in a foreign country with the feeling of joy mixed with guilt of trying to raise a child without the support of family while desperately trying to provide a connection with the customs, traditions and culture from which the immigrant descended.

I am aware of the highly sentimental emotions displayed in these letters, but these are honest and true feelings without any exaggeration. I can say that while writing these letters, they actually wrote themselves. I did not have to embellish, polish or change many of the original words that jumped from my heart to the paper. It is my hope that other Lebanese, Arab and many foreign families read their own reflection in these letters.

February 2013

Monterey, CA

to be continued…