An Attempt to Unravel Some of the Confusion

Surrounding Yemen Cancels, Post Office

by Bruce Conde, Linn’s Stamp News, 16 July 1956

In 1926, His Majesty the Imam Yahia, king of the usually closed and forbidden mountain land of Yemen in southwestern Arabia, inaugurated a royal postal service for the first time, without benefit of outside postal advice and completely unaware of the fact that there was anything in the world called philately. Only eight years before, Yemen was still partly occupied by Ottoman troops, whose forerunner postal service (Hodeida, Taiz and Sana’a cancels on regular Turkish stamps for indifferent and irregular mail to Turkey, mostly by the military) had not been available to the population at large.

Two basic stamps, a “1/2 of 1/8 imadi” (5c U.S.), and “1/8 imadi” (10c US), corresponding to small pentagonal silver coins of the realm (40 bogash—1 imadi—80c U.S.) were produced locally by locking 20 individual cliches together in a single frame for each master sheet.

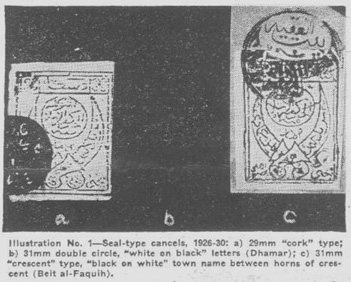

(Seal-type cancels)

Both stamps showed two crossed Yemeni daggers or “Jambiyas” and Arabic inscriptions, with the value spelled out on the left dagger blade. Both were simply black on white, but to avoid confusion due to the lack of clarity of the inscription of value, the low value was eventually painted over with an orange wash, thus creating Scott’s No. 2 and completing the first, or “Jambiya”, set of three stamps, which were imperforate and ungummed.

A sewing machine perforation was subsequently applied to some of the sheets at a nearby local tailor’s for the benefit of postal patrons and post office clerks.

Cancellations were simply enlarged versions of habitual Arabic personal seals, with ornate entwined letters, giving the name of the town, the inscription: “Post and Telegraph” (they were also used for telegrams, as the Turks left a pretty complete telegraphic network throughout formerly-occupied parts of the country) and the year date. These “seal-type” cancels are still used today for telegrams and are occasionally struck on modern stamps during temporary lack of postal cancellers proper.

30 post offices, mostly set up in existing telegraph offices, used the Jambiya stamps and seal-type cancels between 1926 and 1930, and the Yemen Post went merrily on its way, still without outside notice or philatelic ramifications.

The cat got out of the bag with the appearance of the low value stamp on Yemen newspaper wrappers addressed to India, Egypt and Syria—sometimes with additional Indian stamps affixed in Aden, sometimes without additional adhesives—and the issue was first brought to philatelic attention by N.N. Marino and Frank H. Oliver of Bright and Sons stamp firm, in London.

By December of 1926 both English and American stamp journals or columns had noted the Jambiya issue and its seal-type cancels, but very little information about them or the country’s postal service was available until 1930.

Charles R. Crane, America’s first great philanthropist to interest himself in the Arab world, had, in the meantime, sent mining engineer Karl S. Twitchell, as a sort of private Point IV technician, to advise the Imam’s government on development projects. Twitchell, on hearing of the Imam’s desire for international recognition of his sovereignty, suggested that joining the U.P.U. would help.

In 1930 Yemen followed this suggestion, and Yemenite representatives in Germany prevailed on the German Republic’s stamp press to provide the country with an issue of gummed and perforated stamps, on regular German government watermarked paper, in U.P.U. colors. At the same time metallic cancellers, in both Arabic and English, with date wheels running up through the 1940’s, were provided for the 30 existing Post Offices.

Subsequent general issues were variously printed in Berlin, London, Paris, Philadelphia, Vienna and Rome, with over a hundred now listed by Scott and Gibbons. However, there was no corresponding general replacement of the original German cancellers, whose latest available foreign date figures were used in 1949. Makeshift repairs, replacements, and new cancellers for newly-opened offices, on a piecemeal and non-uniform basis have subsequently created a chaotic situation insofar as Yemen P.O. cancels are concerned.

In a 1952 series in MEKEEL’s, entitled “Stamps of Arabia Felix: Postal Issues of the Kingdom of Yemen”, the writer listed all 30 known post offices for the first time.

In 1946-47 the late Brigadier Glynn Grylls, of England, in several issues of the London “Philatelist” described and illustrated both seal and foreign-type cancels and listed 12 post offices of identifiable places, for which he had cancellations on piece or on cover, and mentioning eight others whose locations were unknown to him.

In 1953, while in Yemen, the writer sent a new series to MEKEEL’s, published in the spring of 1954, entitled “The Yemen Post Today”, in which Yemen’s 63 then-functioning post offices were listed, in their Arabic order, as certified by the Postmaster General’s Office.

During the past three years the writer has managed to dig up nearly 30 additional post office names, some of them new offices, others officially reported to the U.P.U., others representing reopened offices which had been dormant in 1953, and others pretty much of a mystery, but all having at one time or another applied cancellations to postal paper.

Of this “complete” list of 90 post offices, which are given below in English alphabetical order, the writes now has 46 identifiable cancellations (marked on the list with asterisks) on cover or on piece, plus a dozen unidentified additional varieties, which boosts the actual number of Yemen post offices to over 100.

Some of the principal types of standard postmarks are illustrated herewith, but as time goes on and more of the decrepit old German cancellers fall to pieces (as that of Mokha did in the hands of the writer, on 3 December, 1953, as he endeavored to cancel a batch of Christmas cards with it), all kinds of weird and unorthodox contraptions are bound to appear, creating confusion compounded. A few of these makeshift concoctions are also reproduced with this article.

Where dates are legible (few, if any with changeable foreign dates will show dates after 1949) more confusion is bound to ensue, for the Yemen Post still uses (largely for accountancy purposes) the defunct Imperial Ottoman civil calendar, long abandoned by Turkey itself.

This was the current dating system when the Imam inherited the remnants of the Ottoman civil service in Yemen in 1918, and as the Turkish bureaucrats knew of no other Moslem solar calendar, those who formed his primitive postal system in 1926, inflicted it on Yemen.

The idea of applying a colored wash to the surface of already-printed stamps also came from the Turks, who has used it on their 1863 issue.

Originally this dating system started with the then-applicable Moslem year date, based originally on the Christian year 622 A.D., the date of the flight of the Prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Medina, known as the Hijra. But as the Moslem calendar is a lunar one, which gains about eleven days a year on our solar calendar, this neo-Hijra calendar soon fell behind the regular one and is now three years behind (i.e. 1372 instead of 1375 A.H.).

Worse, it starts each year from the first of March. Then again, instead of using the Moslem names of the months, or the Arabic civil month names, it mixes the latter with Arabic-spelled foreign months, as follows: “Mart” (March); “Nisan” (April); “Mai” (May); “Huzairan” (June); “Tammuz” (July); “Augus” (August); “Ailul” (Sept.); “Tishrin-Awwal” (Oct.); “Tishrin-Thani” (Nov.); “Kanun-Awwal” (Dec.); “Kanun-Thani” (Jan.); “Shubat” (Feb.).

These are spelled out or abbreviated right after the day of the month figure and appear second from the right on all date lines. Sometimes they are represented by a figure always starting with March as “1”, April as “2” etc.

Going by this system, the date on which the article is written would read “7 Huzairan 1372”, corresponding to the Moslem date “7 Dhulqu’adah 1375” and to the Arab civil (Christian-style) “15 Huzairan (June) 1956”.

In other words, the Turks used the Moslem lunar month day figures (29 or 30 to the month), the Arab civil or foreign month names, and the Hijar year date, now three behind. How they adjust the civil months which have 30 or 31 days instead of 29 or 30, in order to keep up with the sun calendar each year, is just another one of those little mysteries of the Yemen Post with which this writer has not yet caught up.

The writer has long supported Postal Adviser Mustafa Kablawy’s efforts to get postal officials to junk the Ottoman civil date system in favor of either the straight Hijar dates or Hijar plus Christian-type ones, and to order a uniform set of cancellation devices, but apathy, lack of foreign exchange, and a general tendency to solve difficult and perplexing problems by slipping the pertinent papers under the carpet of the royal diwan for an indefinite period, has consistently defeated our combined efforts.

Taking Yemen cancels as they are, here are the respective sizes and characteristics of the most common types to date:

Seal-type, (1926-1930) 20, 23, 25, 29, 30 and 31mm in diameter, respectively. The smaller ones usually contain colorless letters cut into a solid black background similar to our 19th Century cork cancels. Larger types contain outer and inner circles of the same “white-on-black” letter effect, or, occasionally (notably “Beit al-Faqih”), a crescent in this type, with the town name in black on white letters within the horns of the crescent. (See Illustration # 1)

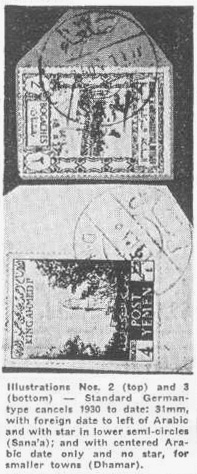

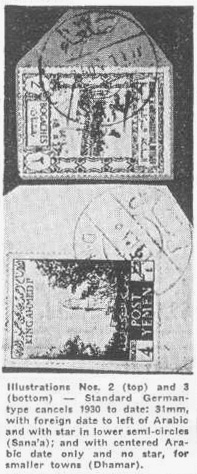

German-type, (1930 to date) 31mm, date band across center, with Arabic date on right, Arabic town name in upper, outer circle, English in lower one, five-pointed star in lower inner semicircle; some without the star; smaller towns, with little or no outgoing foreign mail, omit the foreign date figures and place the Arabic ones in the center. (See Illustrations # 2 and 3.)

Modern adaption of seal-type: Similar to Beit al-Faqih “crescent” type of 31mm seal cancel of 1926 but larger 35mm). See Illustration # 4: Khamar).

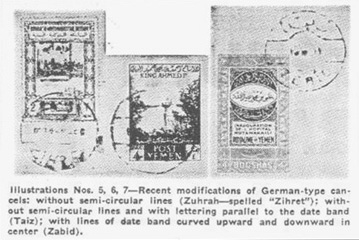

Modifications of German-type:

Without upper and lower semicircle lines, but lettering still following round contour of outer circle 33mm (See Illustration # 5: Zuhrah).

same, but with lettering straight across, parallel to date band, 33mm (See Illustration # 6: Ta’iz); with lines of date band curved upward and down and in center, above and below date (See Illustration # 7: Zabid).

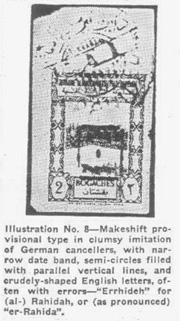

Makeshift provisional types: Clumsy imitations of German cancellers, but with very narrow or with vertical slugs in center, (5mm) date band, usually empty and date figures, if any, at right and left ends; upper and lower semi-circles filled with parallel vertical lines; English letters of town name very crudely shaped and cut, with numerous errors, 35mm (See Illustration # 8).

Spelling of the town names in English letters, at the bottom of most cancellations, vary from German to French to English to versions of unknown origin, Also, the prefix “al-” (the definite article) which is always written in the Arabic version of proper names taking the article, is not always included in the English version. The Arabic “al-Hodeida”, for example, invariably appears as “Hodeida”. The local dialect, which renders “Q” as “g” in “golf”, among other things, also show a tendency to creep into the spelling at the bottom of the new makeshift provisional cancels, Thus, “Gaedeh” for “al-Qa’aidah”, etc.

One thing is for sure—there’s never a dull moment on collecting Yemen postmarks!

1956 LIST OF YEMEN

POST OFFICES

1) ‘Aabs* 31) Ibb* 61) Qa’aidneh*

2) ‘Aadain (al-)* 32) Jebi (al-)* 62) Qa’ataba*

3) ‘Aamran* 33) Jof (al-) 63) Qalaat al-Mendel

4) ‘Aatmeh* 34) Kafr 64) Qarea (al-)

5) Aker 35) Khadir (al-) 65) Qtataba Khaqare

6) Baadan 36) Khamis (al-) 66) Rahidah (al-)

7) Baida (al-)* 37) Kahmr* 67) Raud (al-)

8) Bajil* 38) Kokhah 68) Rawdah (al-)*

9) Bara’ah (al-) 39) Kuhlan* 69) Rida’a*

10) Beit al-Faqih* 40) Lohaiya* 70) Rimeh

11) Ben ‘Abbas 41) Ma’abr* 71) Sa’adah*

12) Biraa 42) Mafalis (al-) 72) Salif (al-)

13) Dar al-Nasir* 43) Mafhaq 73) SANA’A*

14) Dhamar* 44) Mahabishah (al-)* 74) Sayaneh (al-)*

15) Dhisifal* 45) Mahwith al-)* 75) Sha’ar (al-)

16) Doran (Anes)* 46) Maidi 76) Sheikh Said

17) Fira’a 47) Makha (al-) (Mokha)* 77) Shibam*

18) Hijdah 48) Makhader 78) Sukhneh

19) Hajjah* 49) Manakha* 79) T’AIZ*

20) Harf (al-)* 50) Mandeb (al-) 80) Tawileh (al-)*

21) Harib 51) Mansurieh (al-) 81) Thila

22) Hasha (al-) 52) Maqbanah 82) Wisab al-A’ail*

23) Heyflan 53) Marib 83) Wisab al-Safil*

24) Hiraz 54) Mawiah* 84) Yafriz

25) His 55) Mawzaa 85) Yarim*

26) Hodeida (al-)* 56) Misbah 86) Zabid*

27) Hobish 57) Mozar 87) Zemir

28) Hojeriah (al-) 58) Murawi’ah (al-) 88) Zeidia*

29) Hojeilah (al-)* 59) Nadira (al-)* 89) Zubab

30) Huth* 60) Qa’aidah (al-)* 90) Zuhrah (al-)*