By Gregory Starrett

UNC Charlotte

“Now, the characteristic feature of mythical thought. . .is that it builds up structured sets. . .by using the remains and debris of events. . . .Mythical thought for its part is imprisoned in the events and experiences which it never tires of ordering and re-ordering in its search to find them a meaning.â€

Claude Levi-Strauss, The Savage Mind

In a previous post, Desiree Marshall faulted director Thomas Gaghan’s recent movie Syriana, implying that a combination of bias and ignorance spoiled what might otherwise have been a useful exploration of identity and politics in the Middle East. While her misgivings are likely shared by others, she and most of the film’s other reviewers have missed its point entirely. Syriana is not at all “about†the Middle East except in the sense that it uses the debris of current events to reveal larger truths and tell much older stories. In fact, Syriana is what French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss would recognize as a structural transformation of another tale: director William Friedkin’s 1973 screen version of novelist William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. The two films are variants of the same myth.

As you recall, The Exorcist concluded with the efforts of two Roman Catholic priests, Father Lankaster Merrin (Max von Sydow) and Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) to free twelve year old Regan MacNeil (played by Linda Blair in a role which both made and destroyed her film career) from her possession by the ancient Sumerian demon Pazuzu (bringer of droughts, locusts, and famine). The majority of the film leading up to the exorcism itself concerns Regan’s frightening psychological and behavioral symptoms, and her mother Chris’s (Ellen Burstyn) efforts to diagnose and treat them, culminating in her abandoning medical explanations and persuading a skeptical Karras, who is also a psychiatrist, to harness the power of Christ through the ancient ritual. They race against time as a police detective (Lee J. Cobb) investigates a murder Chris suspects her possessed daughter has committed.

Syriana concerns a broad cast of characters, including Bob Barnes (George Clooney), a weary CIA operative, Brian Woodman (Matt Damon), an American energy analyst who has been hired as chief economic advisor to Prince Nasir Al-Subaai (Alexander Siddig) after Woodman’s son accidentally drowns in the Prince’s pool; and Bennett Holiday (Jeffrey Wright), a lawyer investigating shady dealings in an energy company merger facilitated by senior partners in his own law firm. Meanwhile, young Pakistani oil field worker Wasim Khan (Mazhar Munir) and a friend are thrown out of work as a result of international corporate machinations they cannot control, and are drawn into the orbit of an Egyptian militant associated with a local Islamic school, who eventually sends them on a suicide mission to destroy an oil tanker.

Surprisingly, the initial clue that these two stories are merely myth variants concerns not their underlying form, but their manifest content. Both films begin in exactly the same way: with the lilting Arabic call to prayer introducing the initial visual image: a massive crowd of bustling laborers. In The Exorcist, the first scene shows workers near Mosul, Iraq, excavating the ruins of Nineveh with picks and shovels in the bright sun. In Syriana, the first scene is of South Asians fighting to board a labor contractor’s bus in the misty dawn, to be taken to the oil fields of the rich Gulf kingdom. Although subsequent characters and events appear quite different on the surface, the two versions of the myth in fact fall quite neatly into line:

The Exorcist: Father Merrin spends decades battling the forces of evil, knowing no final victory is likely.

Syriana: CIA Agent Barnes spends decades battling the forces of evil, knowing no final victory is likely.

The Exorcist: Regan consults a Ouija board, the gatewayto spiritual corruption and to her eventual entrapment by the demon.

Syriana: The kingdom’s royal family consults powerful Washington lawyers, the gateway to spiritual corruption and their eventual entrapment by U.S. moneyed interests.

The Exorcist: Father Karras loses his beloved mother, and worries that he is partly to blame.

Syriana: Woodman loses his beloved son, and worries that he is partly to blame.

The Exorcist: A police officer, living with but estranged from his wife, investigates wrongdoing.

Syriana: A lawyer, living with but estranged from his father, investigates wrongdoing.

The Exorcist: Chris McNeil tries to solve her daughter’s painful symptoms of possession.

Syriana: Prince Al-Subaai tries to solve his country’s painful symptoms of underdevelopment.

The Exorcist: Person(s) unknown desecrate a church with perverted version of Catholic imagery.

Syriana: Egyptian Islamist encourages suicide attack with perverted version of Islamic imagery.

The Exorcist: When doctors fail, MacNeil turns to the hesitant Karras, who fears he has lost his faith.

Syriana:Â When other solutions fail, Al-Subaai turns to the hesitant Woodman, who fears he is selling his soul.

The Exorcist: Karras relinquishes psychiatric objectivity, joins personally in fight against demon

Syriana:Â Woodman relinquishes analytical distance, becomes personal advisor to Prince.

The Exorcist: Karras tormented by demon, who manipulates his guilt over his mother’s death.

Syriana: Woodman estranged from his wife, who manipulates his guilt over his son’s death.

The Exorcist: Merrin and Karras cooperate to save Regan separately from the demon.

Syriana: Barnes and Woodman work to save Al-Subaai from American threats.

The Exorcist: Merrin dies of a heart attack. taken by the demon, is Karras killed in fall. Regan survives, without memory of her ordeal.

Syriana: Barnes dies in a U.S. Predator missile attack. Woodman survives attack, returns to his family, the slate clean.

Clearly the two variants, though hardly concurrent on the surface after the very first scene, are structural equivalents. Part of Levi-Strauss’s methodology for myth interpretation was to disregard the discrete elements of myth variants and to identify instead the bundles of relations that connect those elements. Variants can be analyzed separately in this way, or variants can be compared using a number of techniques that reveal internal systems of opposition and mediation.

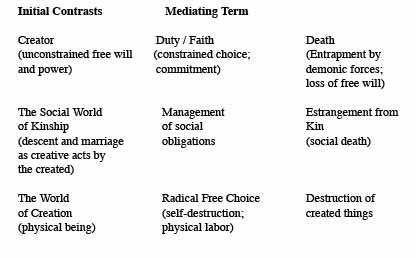

The films’ beginning provides us not only with the initial clue to their identity, but with the terms in an initial opposition that structures both tales. This is the juxtaposition of the call to prayer, “God is Great,†and the visual depiction of laborers who extract scarce resources from the earth, destroying those resources as a result (excavation destroys archaeological sites; the oil produced is to be refined and burned). The core opposition here is the original and life-giving work of the Creator God, on the one hand, and on the other his creation, where acts of subsistence are also acts of destruction. In the following table, the contrast sets are multiple, and can be read either down or sideways, beginning with the pairs of oppositions at each end, each pair mediated by the middle term.

The initial opposition between Creator and creature is mediated by the element of kinship, one of the most important themes in both movies. Chris MacNeil’s fierce devotion to her daughter in The Exorcist is matched by Syriana’s Prince Al-Subaai, who is just as fiercely devoted to the people of his kingdom, his figurative children, and by both Woodman and Barnes, whose devotion to their families is not always reciprocated (Regan also rejects her own mother’s care during her possession).

Likewise, the opposition of Life and Death, freedom and entrapment, is mediated by the value of spiritual duty, which, in its own opposition to physical labor, is mediated by the management of social obligations, the choice of to whom loyalty and self-sacrifice is granted. For both priests in The Exorcist, and for CIA operative Bob Barnes in Syriana, the choice is made to sacrifice themselves for specific non-relatives (Regan, Prince Al-Subaai). Both are destroyed by powerful demonic forces (Pazuzu, American moneyed interests). For laborer Wasim Khan and his friend, on the other hand, self-sacrifice is chosen on behalf of a broader but invisible umma which, they have been convinced, is endangered by those same forces. They sacrifice their lives as they had previously sacrificed their bodies and their health through their unwitting labor on behalf of the demon itself.

At the end of The Exorcist, the wise and experienced Father Merrin tells Father Karras that the reason demons so torment the innocent is to try to convince us that humans are ugly and unworthy of love; shut off, in other words, from the possibility of human attachment. What Syriana’s Egyptian Islamist offers his two young recruits was even more quotidian and even more basic, and even less available than love to the two underemployed youths. “At the Islamic School they gave us French fries,†Khan’s friend recalls in the midst of conversation amongst a group of friends in a worker’s barracks. A little later he returns to the theme: “At the Islamic School, they gave us lamb.†There is no other message in the two films than this: that theologies are of scant importance compared to simple human expectations of love and physical sustenance and hope. And that when these expectations are threatened with being torn apart by forces that seem beyond our control, the fight against these forces has a way of claiming lives.

Gregory Starrett