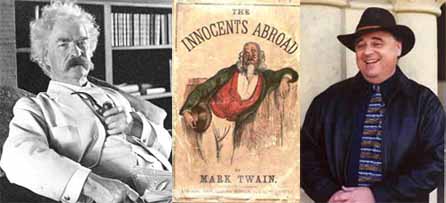

[Mark Twain, left; early cover of ‘Innocents Abroad’, center; Hilton Obenzinger, right]

by Hilton Obenzinger, Stanford University

Innocents Abroad’s manufacture of “Mark Twain†as the surrogate for the reader’s “own eyes†was immensely popular. The travel book, whose sales reached 100,000 even before the second anniversary of its publication, launched, even more than his celebrated jumping frog, Mark Twain’s national career. “Popular as are Mark Twain’s books at home,†an unidentified correspondent for the Hartford Courant reported in 1872, Innocents Abroad is “still more so abroad.â€

“It sells right along just like the Bible,†Mark Twain remarked to William Dean Howells. Indeed, half a million copies had been sold by Twain’s death in 1910, at which time Innocents Abroad, with its central organizing principle of “Mark Twain†as “one of the boys†joined Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer as the titles (and two other boys) most commonly worked into political cartoons memorializing the author in the press. Today Innocents Abroad, still a pleasure to read despite the complications and vexations of history, remains durable, continuing to be hailed as “the most popular book of foreign travel ever written by any American.â€

Much of Innocent Abroad’s early popularity arises from the fact that despite Twain’s boast that he “basked in the happiness of being for once in my life drifting with the tide of a great popular movement†(27), he seems to swim against that very tide—or at least against the tide of expected, genteel responses to touristic locales. The Quaker City adventure, the first organized American tourist excursion—“its like had not been thought of before†(19), even anticipating the first of Thomas Cook’s “Eastern Tours†by 2 years—allows Twain to reinvent the traveler as a consumer of sights through a volatile rhetoric of perception, value, and authenticity that is both playful and explosive. Innocents Abroad extends the already iconoclastic inclinations of Americans into (and beyond) irreverence, marking the transition from travel as some kind of unique experience of social, aesthetic, and spiritual relations (such as Abraham Lincoln may have anticipated) to an exercise in the accumulation of cultural commodities.

Innocence is played off against experience, naivete against sophistication, trust or confidence against fraud, authenticity against inauthenticity, with the “New Pilgrim’s Progress†of the book’s subtitle even playing off the attainment of grace against sin by means of the illusion of “the reader’s own eyes.†Even the prospectus of the book—which was used to sell Innocents Abroad door-to-door by subscription—announces that “no one will rise from its reading without having a better and clearer knowledge of the countries it describes than ever before, and more ability to judge between truth and fiction in what he may read respecting them in the future.†Yet what remains fascinating is that fact that the play of this duality—“truth and fictionâ€â€”is posed by a confidence-man himself, a shifty narrator who constantly inflates his own illusions in order to puncture them, who repeatedly engages the reader’s trust by pulling his “mark†willingly within the tall tale’s interpretive circle of complicity to discover “truth†while at the same time destabilizing the certainty of it altogether through laughter—a masterful “poker-faced†performance underscored by Mark Twain’s own deadpan delivery of his “American Vandal Abroad†lectures before the actual publication of the book.

Excerpt from Hilton Obenzinger, American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999)), pp. 164-166.