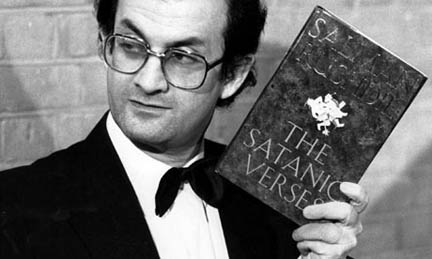

Salman Rushdie, author of The Satanic Verses

[The following is part five of a series on a lecture presented in the Hofstra Great Books Series on December 5, 1993. For part four, click here.].

The Struggling Believer’s Novel and the Text

I could easily continue this discussion of the views of Ibn al-‘Arabi for hours, days, or weeks (how long would it take to simply read 17,000 pages in his major work?) It is valuable to probe with a believer like this great scholar into the depths of his own meaning-rich search through the language of the Quran. But much has happened in the past 750 odd years in the Islamic World. Muslims, through no fault of their own, have been caught up in a broadening discourse defined in large part by the overtly Christian West, even though any distinctive Christianness may have largely eroded. In contrast, Ibn al-‘Arabi lived in a world in which the Quran’s detractors — those who did not grapple with this Arabic text as a revelation — were few and far away. To be sure there were debates over the form of the revelation, although these were tilted to orthodoxy rather early on. But in his day there was no viable reason in the Muslim context not to accept the Quran as revelation.

Muslims over the past couple of centuries have been compelled to defend the Quran against what they believe is a secular war aimed at the integrity of their religion. The heartland of Islam since the 16th century has been dominated by Ottoman Turks (Muslim converts, it must be remembered) up until this century, with European colonial powers nibbling away at the often frayed edges of the Sublime Porte. The more recent raw power politics of this century, be this the regimen of Western-trained military elite takeovers, the imposition of secular Israel in a predominantly Islamic Middle East, the cleric-driven drive for a militant, rejectionist radicalism in Iran and Afghanistan, the dirt-poor rage of simple Egyptian fundamentalists, the cold war Sadaamizing of Kuwait, the collective blinking as Bosnia bleeds non-Christian blood — these events have sharpened the frustration and anger of Muslims wherever they are. And at least three out of four Muslims are not in the Middle East. While we only rarely see these events on our evening news, for Muslims they are far more than ubiquitous sound bites; they are rather like pages torn without mercy, without compassion from their great book.

Ironically, the Islam that we mistakenly think spread out of an uncouth tribal Arabian wasteland by the sword, has been most wounded not by earlier crusader zeal, nor by recent batteries of patriot missiles, but by the pen of a struggling believer, a single man born Muslim in India but bred in the marginal literary circles of a country which once fancied it owned India. A wounding, I might add, that may with some justification be called “self-inflected.” This one man, who now lives in hiding with a price placed on head, has been more vilified by contemporary Muslims of many persuasions around the world than any other single individual I know of — Muslim or non-Muslim. I speak of Salman Rushdie, author of the avowedly controversial novel The Satanic Verses in 1989. While Rushdie the author does not wear his Islamic identity on his sleeve, he is well aware in real life that his Islamic origin — a significant part of the otherness that haunts his search for identity –defined him as an outsider in a culture he thought might let him embrace it as an equal.

The irony is unending. Although very few Muslims and only a few non-Muslims have actually read through Rushdie’s novel — a 550 some page stream of dialogue that bedazzles and befuddles through a sweeping fantasy — we in the West are far more aware of the Islamic backlash against Rushdie and his verses than we are of the essential fatiha that opens the Quran or the theology of a scholar like Ibn al-‘Arabi. For the past five years indignant intellectuals and defenders of human rights have come to Rushdie’s rhetorical defense, all the while chiding Muslim intellectuals for not rushing to do the same.

The West sees the death warrant issued against Rushdie by Khomeini (who ironically has tasted death first) as clear evidence that Islam is repressive and reactionary, not fit to be ecumenical in a new secular world order. On the other hand, I fully realize that the mere mention of The Satanic Verses, not excluding my own remarks tonight, tends to send a message to Muslims that their religion is not taken seriously. I might point out, however, that a fellow anthropologist, Prof. Akbar Ahmad (who happens to be Muslim) of London University, has recently argued that “no contemporary discussion of Muslim scholarship can be complete without reference to the controversy surrounding The Satanic Verses.” (PostModernism and Islam, 1992, p. 169). I would only add that Western non-Muslims can not fully appreciate how Muslims see the greatness of the Arabic Quran without understanding why a rather odd English novel has provoked such rage in Islamic countries where English novels are seldom if ever read.

It is not my intent to defend or critique Rushdie’s novel anymore than I would the Quran in this talk. The novel is — for anyone who takes the time to read it — as fantastic as our cinematic representations of the original Arabian Nights. It tells us no more about Islam than Disney’s Aladdin informs us about the Baghdad caliphate. Indeed, those who skip through looking for the satanic parts will be disappointed to find that much of the dialogue is between displaced Indian movie stars who can afford to escape the thirdworldliness of India for their civilization’s Mecca — England.

At the start of the fantasy two Indians-who-would-be-English are in free fall after their airplane is blown apart in the air by a terrorist bomb. One of these is the star of Rushdie’s semi-autobiographical fantasy, Gibreel Farishta. Yet more irony … the novel begins with lines of a decidedly Christian rhetoric:”‘To be born again,’ sang Gibreel Farishta tumbling from the heavens, ‘first you have to die.'” Absurdly, Gibreel and his companion survive the fall, an occasion, Rushdie writes, for a National Holiday in England. “But,” (and this is the gist in the novel’s own words) when Gibreel regained his strength, it became clear that he had changed, and to a startling degree, because he had lost his faith.”

Rushdie writes on, hilariously yet unendingly for all but the most stalwart of his supporters, in the same free-fall, a half-awake, half-asleep dreamtime in which the details he learned as an Indian Muslim about Muhammad and the Quran come in and out of focus as clearly planned distortions to anyone who knows the original. Gibreel is himself a phantasm of the angel Gabriel, whom Muslims revere as the agent who brought the revelation to Muhammad, also the angel who introduced this “seal of the prophets” to his fellow prophets — Abraham, Moses, Jesus, etc. — during Muhammad’s fabulous, pre-Dantean night journey through the layers of heaven.

Someone who is not a Muslim would not generally recognize the extent to which Rushdie plays with Quranic passages and the life of the prophet, who is fantasized here as the unscrupulous Mahound, a none-too-subtle Jim Baker or Jimmy Swaggert type, and a long-standing synonym in English nuance, as it happens, for Satan. For Muslims the title The Satanic Verses says it all. These Satanic verses are not the product of Rushdie’s rather fertile imagination; they refer to an issue that Muslims have debated for some time. Some have argued that Muhammad once uttered words that allowed praise for three of the goddesses of Mecca, obviously more than a minor inconsistency with this monotheistic revelation as it was canonized. These controversial verses, which Rushdie builds a substantial part of his novel around, were later said to be abrogated by Muhammad when he learned in a subsequent revelation that they had been inspired by the Devil (Satan) rather than God. Whether or not this actually happened from a Muslim perspective is besides the point. It happens to hit a very raw nerve for Muslims, since it is one of the most potent symbols of blasphemy in Islam; and Rushdie obviously knows that.

The origins of Islam are revisited in the novel in a mythical place called Jahilia. While this would be read as just another exotic name by most non-Muslims, it is instantly recognized in Arabic as a reference to the paganism of pre-Islamic Arabia. The days of Jahiliya, literally “days of ignorance” were precisely what Muhammad condemned and what Islam would supercede. Rushdie spares little in satirizing the sacred history of the prophet Muhammad. For example, at one point Gibreel complains at length that Mahound’s “revelation of convenience” is too legalistic, even giving rules on which way to face after a man farts (p. 363). While a non-believer may simply not care about such literary games — after all the Quran is not seen as a revelation in the first place — or may at most cry “shame,” most Muslims feel betrayed. It is betrayal because it comes from one raised as a believer, not from an outside enemy.

Imagine if your best friend wrote you a letter in which he or she fantasized about having kinky sex — and more than kinky — with your spouse. Let us assume the letter was about thirty pages long and was quite descriptive, including variations of taped conversations of your actual spousal love-making. And then he or she told you it was not meant as a joke, that there was a passion that could not be denied and this was simply a way of working it out although still remaining your best friend. If this simple mundane letter could anger you, how much more if it were the distortion of a sacred book that you think is the greatest book because it came directly from God?

to be continued