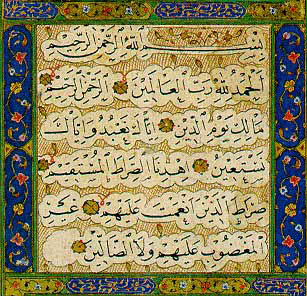

The fatiha in an Arabic manuscript of the Quran

[The following is a lecture presented in the Hofstra Great Books Series on December 5, 1993].

بÙسْم٠اللَّه٠الرَّØْمَٰن٠الرَّØÙيمÙ

الْØَمْد٠لÙلَّه٠رَبّ٠الْعَالَمÙينَ

الرَّØْمَٰن٠الرَّØÙيمÙ

مَالÙك٠يَوْم٠الدّÙينÙ

Ø¥Ùيَّاكَ نَعْبÙد٠وَإÙيَّاكَ نَسْتَعÙينÙ

اهْدÙنَا الصّÙرَاطَ الْمÙسْتَقÙيمَ

صÙرَاطَ الَّذÙينَ أَنْعَمْتَ عَلَيْهÙمْ غَيْر٠الْمَغْضÙوب٠عَلَيْهÙمْ وَلَا الضَّالّÙينَIn the name of God, the infinitely Compassionate and Merciful.

Praise be to God, Lord of all the worlds.

The Compassionate, the Merciful. Ruler on the Day of Reckoning.

You alone do we worship, and You alone do we ask for help.

Guide us on the straight path,

the path of those who have received your grace;

not the path of those who have brought down wrath, nor of those who wander astray.

What I have just recited in Arabic is the Quran’s opening or fatiha, consisting only of seven short verses, the first of some 114 chapters of varying length. This is the most oft repeated part of the Quran, recited daily by millions of Muslim men and women during each of the five regular prayers. So integral are these opening words in the revelation of Islam that they have been called the “essence” (literally “mother”) of the Quran (Umm al-Quran ), or as some say, “the Lord’s Prayer of the Muslims.” This fatiha is the opening salvo of a scripture revered as God’s most basic message by more than one billion people on earth today. For these Muslims, most of whom live outside the Middle East, the Arabic Quran is not only a great book but quite literally “the” great book. While non-believers would not approach this book as a true revelation, no one can deny that it is a scripture that has been influential in shaping history across continents for almost 15 centuries and will continue to influence the lives and politics of many of the world’s peoples for a long time to come.

My interest tonight in talking about the Quran differs somewhat from most of the lectures in this series. I feel no need to convince you as an audience in an academic setting that the Quran is a significant text, one of those few great books that we cannot afford to ignore. This is made even more poignant in light of the perceived threat by many in our society of a so-called “militant” Islam on the march against Western Civilization. In our collective cultural ignorance, the Quran is portrayed only as a manifesto, not because non-believers do not take the time to read it carefully but simply because Islam has been branded as a hostile and uncompromising worldview.

I am not an apologist for Islam, and if I were this would hardly be an appropriate forum to try and convert you to a religion that is arguably more misunderstood and belittled than the other fashionable monotheisms we know about. Nor do I wish to stand here in the guise of a well-intentioned, dispassionate, outside observer of a religious and intellectual tradition I was not born into nor bred up in, even though I have interacted with this tradition enthusiastically over the course of two decades. I am not interested here in laying out a critical assessment of the Quran as a literary text — deconstructing a revelation as anything other than a revelation. The Quran as literature would only make sense with a focus on the “Arabic” text; in this I totally agree with the Muslim perspective that the Quran can never be properly translated out of Arabic. All such “translations” are but shadows to any Muslim without the vitality and force of the original. There can be no “King James Version” of the Islamic holy book. I am certainly not one whit motivated to attack the authenticity of the Quran, to argue either ethnocentrically that it is a poor hand-me-down copy of the Judaeo-Christian scriptural lineage, nor to engage in an exegetical exercise to ferret out myth textually in that peculiar academic penchant for defining real truth as historical truth.

to be continued