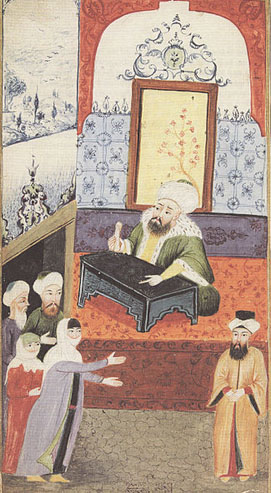

An unhappy wife is complaining to the Qadi about her husband’s impotence, 18th century.

Fresh Air, NPR, April 16, 2012

Sadakat Kadri is an English barrister, a Muslim by birth and a historian. His first book, The Trial, was an extensive survey of the Western criminal judicial system, detailing more than 4,000 years of courtroom antics.

In his new book, Heaven on Earth, Kadri turns his sights east, to centuries of Shariah law. The first parts of his book describe how early Islamic scholars codified — and then modified — the code that would govern how people lead their daily lives. Kadri then turns to the modern day, reflecting on the lawmakers who are trying to prohibit Shariah law in a dozen states, as well as his encounters with scholars and imams in India, Pakistan, Syria, Egypt, Turkey and Iran — the very people who strictly interpret the religious and moral code of Islam today. And some of those modern interpretations, he says, are much more rigid — and much more draconian — than the code set forth during the early years of Islamic law.

Islamic law is shaped by hadiths, or reports about what Prophet Muhammad said and did. The hadiths, says Kadri, govern how Muslims should pray, treat criminals and create medications, among other things.

“It’s a huge oral tradition, which was set down in the 9th century and which was then, by some people, transformed into compulsion and rules,” Kadri tells Fresh Air’s Terry Gross. “It would be literally impossible to follow all of them, because plenty of them directly contradict each other. So you have to make choices, and Muslims have been making choices for … the last 1,400 years. And what’s happened over the past 40 years is that in certain places, the hard-liners have come to the forefront.”

In the early 1970s, Libya, led by Moammar Gadhafi, became the first country to introduce Islamic criminal penalties outside of Saudi Arabia; Pakistan and Iran followed suit in 1979. Throughout the past three decades, the number of countries applying harsh interpretations of Islamic law has expanded.

“One thing I realized when traveling around the Muslim world is how closely these hard-line interpretations of Islamic law are associated with political consternation and turmoil,” he says. “There isn’t a country anywhere in the Muslim world which has been applying Muslim laws continuously for hundreds of years and which is drawing on genuine tradition. It’s a revival of supposed traditions, which don’t really pay much heed to history at all.”

Kadri addresses the hard-liners in the prologue to Heaven on Earth, which starts with a disclaimer: “Lest it be necessary to say so — and it probably is,” he writes, “[this book] does not intend at any point to challenge the sacred stature of the Prophet Muhammad, the self-evident appeal of Islam, or the almightiness of God.”

Kadri says he wanted to make it clear that his book was not out to offend.

“It’s a disclaimer to the extent that I’m pointing out what I’m not contesting,” he says. “I’m not arguing the fundamentals of Islam. What I’m arguing about is the interpretation that’s been put on those fundamentals over the last 1,400 years. And what I’m arguing about is the interpretations of Islamic law that are being presented as sacred by hard-liners. And that, I think, should be a proper subject to debate.”