The following news item just came across the wires from Arab News, an English language daily based in Saudi Arabia. Think of your gut reaction as you read…

SANAA, 3 January 2006 — Tribesmen holding five Italian tourists hostage in northeastern Yemen yesterday threatened to kill them if troops encircling the area move to rescue them, a local official said.

The five Italians, three women and two men, were snatched from Marib, some 195 km northeast of the capital Sanaa on Sunday and taken to the Serwah district, about 30 km away.

The kidnappers, who belong to the Al-Zaidi tribe, have demanded the release of eight clan members being held in Sana’a in connection with the killing of a police officer in the city in 2003.

One of the kidnappers, a tribal identifying himself as Mubarak Mabkhout Al-Zaidi, told Arab News by mobile phone: ‘I swear that if a single shot is fired we will kill them. We are neither saboteurs nor terrorists. All what we want is to negotiate the release of our men detained by authorities.’

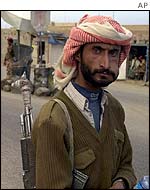

Given the history of hostage taking of Westerners in Iran, Lebanon and now Iraq, it is understandable that a reader’s first reaction would be yet another case of international terrorism, this time in Yemen. But such a quick judgment would be wrong. My point is not to justify kidnapping, which is a rather rude way to negotiate demands anywhere. But Yemeni history is replete with such kidnapping by tribesmen in order to get the attention, which such an act generally does, of a government they think has wronged them. As the Yemeni tribesman says in the story above, he is not a terrorist acting out of anger at Westerners.

The majority of foreigners “kidnapped†in Yemen over the past couple of decades have been unharmed. Some actually describe the event as a kind of holiday in which they were feasted as honored guests. When deaths do occur, it is usually not by tribesmen, as when three Britons and an Australian were shot dead in December, 1998 by Yemeni security forces storming a mountain hideaway in the Abyan district. These hostages had been taken by a group said to be affiliated with al-Qaida. Abu al-Hassan, the self-styled leader of the group, was caught and eventually executed by the government of yemen. Of the 157 foreigners kidnapped in Yemen from 1996 to 2001 the only five that died were victims of the rescue attempts.

The latest kidnapping follows on the heels of the abduction last Wednesday of Mr. Juergen Chrobog, 65, a former deputy foreign minister of Germany and former ambassador to the United States. Mr. Chroborg, his wife and three children were released unharmed on Saturday.

If tourists are not being taken in retaliation for American foreign policy in the Middle East, why does this happen so often? In part the problem lies with the inability of Yemeni security forces to control the entire country, especially tribal areas near the border with Saudi Arabia. But the resort to kidnapping someone at hand, whether a foreigner or a government official, is a tried and true political act stemming back to the times of the imams in the early 20th century.

To understand why such acts should not be labeled “terrorism,†at least in the sense of the beheadings that have occurred in Saudi Arabia and Iraq, it is important to consider the nature of tribal conflict and mediation in Yemen. A recent book that does just this is Steven C. Caton’s recently published Yemen Chronicle: An Anthropology of War and Mediation (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005). In 1980, while conducting ethnographic fieldwork on Yemeni poetry, Caton was embroiled in a local tribal war in Khawlan, east of the capital Sanaa. Through no fault of his own, he was abducted by security forces for questioning, held for several days and finally released. This is not a bitter and vengeful book, but a warm and eloquent reflective account of a unique experience. This is the kind of book, eminently informative and entertaining at the same time, that provides needed insight on ordinary news stories that only scratch the surface of events.

Daniel Martin Varisco