The British diplomat Sir Valentine Chirol (1852-1929) wrote a memoir entitled Fifty Years in a Changing World (New York: Harcourt and Brace, 1928). Among the areas in the Middle East that he visited or commented upon were Egypt, Syria, Ottoman Turkey, Persia and the Persian Gulf. He also has some interesting observations on India, Japan, the Balkans, Berlin and Russia. Of particular interest is his commentary on Egypt in 1876 before the British occupation. Below is an example of that.

Category Archives: Egypt

Online Books in Halle

Facebook on King Farouk

King Tut’s Tomb in Color

Nice site with photos of the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922.

Being Si Al Sayed

Music videos in the Arab world, and not least in Egypt, are at the same time widely viewed, popular and relatively understudied. They can reflect pressing contemporary issues, controversial political topics, and, which I aim to explore here, express idealised forms of gender performance. Evoking the literary character Si Al Sayed, created by Egyptian Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz, artist Tamer Hosny aims to reproduce a traditional masculinity, marked by a patriarchal position of men as “head of the household.”

Si Al Sayed is a reference to a literary and cinematic character, created by the late Egyptian writer and Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz. The character is known for his controlling and tyrannical demeanor, thinking that his position as “the man of the house” means absolute authority, and because of this he is also a respected and revered character by many men. In fact, as odd as it may sound, the unequal marriage of Al Sayed is often seen as a model marriage. An example of this is the eponymously titled “Si Al Sayed” by Egyptian artist Tamer Hosny, who compares himself to Mr. Al Sayed, and featuring American rapper Snoop Dogg.

In an analysis of Egyptian actor Farid Shauqi, Walter Armbrust (2000) writes that the tough guy ideal took ultimate form as family patriarch and as national hero, and concludes that “it was a short step from defending the honor of one’s woman to defend the honor of the nation.” While conducting field studies in Egypt in 2014, aimed at exploring men and masculinities in Egyptian media, I reached a similar conclusion. In that study, the respondents associated masculinity as much with family obligations – men as providers and protectors – as they did with a national obligations – men serving the nation – emphasised through ideas of strength, courage, and honor. The position of “the patriarch”, as such, relates to both the family and the nation.

In the song and music video for “Si Al Sayed,” Tamer Hosny makes use of the literary figure, visually attempting to evoke this form of masculinity. As such, he also reproduces and reinforces an enactment of masculinity that relies on marital inequality, male dominance and female oppression.

The music video begins with a text explaining the title: ‘An Arabic term referred to an old movie character that likes to control everything in his life.’ This is followed by a camera panning down on Tamer Hosny sitting in an egg chair suspended from a high ceiling, swiping on an iPad, in front of a huge window overlooking Beverly Hills. Cut to a woman painting her toe-nails in bed, in another part of the house. She is wearing big bracelets, and the bed is covered with jewelry and fashion magazines. She yells loudly at Hosny, using a high pitch, scolding him for inviting a friend over, saying that she wanted them to go out to have sushi. Hosny answers by saying “sushik? Allah yiraam!” literally meaning “sushi? God have mercy!”

After dismissing his partner as crazy, he gets up to let in his friend, Snoop Dogg. They greet, and the woman, still in her bed, yells “TAKE YOUR FRIEND AND LEAVE RIGHT NOW!!!” Hosny goes through a series of facial expressions, beginning with a sort of shock, followed by embarrassed confusion. He looks at Snoop who nods at him in a way that asks “what are you going to do about this?” She yells again, and it is captioned: “TAMERRRR!!!!!!!!” He looks at Snoop again, who points and nods towards her room. Hosny raises his eyebrows, as if to say “I guess I need to do something,” and goes to speak with her.

In Egyptian cinema, there is a common trope of “masculinity in crisis,” wherein the protagonist has his masculinity challenged in some way, either through harassment from corrupt authority officials, an inability to provide for his family, or being controlled by his partner. This acts as a set-up for the protagonist to reassert himself, “as a man.” This introductory scenario in Hosny’s music video functions in the same way, portraying a masculinity in crisis.” Hosny is portrayed as a man without control of his partner, thus propping him up to reassert himself and “earn” his masculinity, by taking the role of the ultimate, authoritarian patriarch, symbolised through the character of Si Al Sayed.

There’s only one man in the house, baby. And he wears the pants, so dance. (Snoop Dogg, in “Si Al Sayed”)

Hosny repeats his claim that she is crazy, following it up by asking how she can talk to him “that loud in front of the guy?” She responds that she will talk to him however she likes, and that he should not act like he’s Si Al Sayed. The music starts playing and Hosny thinks for a short while, before the camera cuts to him locking the door to her room, leaving her inside. This is immediately followed by several shots showing a house party, apparently hosted by Tamer Hosny.

The music video reveals that behavior and expression can be used to assert a social position, or at least evoke a characteristic (authoritative masculinity) that was not there initially. This does not mean that masculinity can be reduced to behaviour and expression, but that they functions to reproduce popularly held ideas about what it “means to be a man.” In some ways, Hosny alludes to the already established role saayia’, meaning “bad boy,” or “tough guy.” On the one hand, his claim to masculinity is based on the control of his partner, which is not saayia’ since it means he is not independent, but on the other hand, he appears to represent himself as a womanizer, which definitely is related to saayia’. In the party scenes, he is surrounded by women, who are seemingly only there to affirm his sex appeal and heterosexuality, although his direct engagements with the women of the music video are few. He rarely touches anyone, and most of the attention is presented as one- sided, as admiration of Hosny from the side of the women. This could be a way of both highlighting the sex appeal of Hosny, while portraying him as an honest, faithful and monogamous man.

The typical crisis of masculinity, at least in Egyptian sha’abi cinema, is the inability for a man to support a family. Unemployment, poverty and the inability to make a living is used to represent this crisis. It could therefore be argued that the extravagance of Hosny’s party is meant as another confirmation of his masculinity, represented through economic power, and thus his ability to provide. His masculinity, in other words, is far from challenged in this regard, making the many signs of wealth into deliberate indices of social, masculine status, meant to counteract the initial crisis. Furthermore, this casts his partner as greedy or ungrateful for not appreciating his ability to provide for her economically. But, it also means that Hosny is clearly separated from sha’abi, blue collar masculinity. Instead, he chooses to aim for an upper class masculinity, part of a capitalist culture placing value in material things and an urbane or suave character.

Usage of English and the fact that the video is set in Beverly Hills are signs of cosmopolitanism, further separating the enactment from the Egyptian public, although the music video is clearly meant to address an Arab audience. Si Al Sayed is a decidedly Egyptian cultural reference, the dialogue is almost entirely in Arabic, even between Hosny and Snoop Dogg, and the lyrical references are more Egyptian than American. It is primarily in the Egyptian context that Hosny’s performance becomes meaningful, not least because of the reference to Si Al Sayed. As such, there seems to be an internal struggle, between the mass appeal of popular, sha’abi, low brow culture, and the flair, extravagance and idealisation of upper-class cosmopolitanism.

It could also be argued that the collaboration with Snoop Dogg, the setting in Los Angeles, and the mixture of English and Arabic (although with a clear preference for Arabic) can be seen as a struggle between an aim for a globalized audience while keeping the massive popularity and following amongst an Arabic-speaking audience. The alternative interpretation would be that these aspects appeals to an Americanised music scene, or acts to highlight Hosny’s successes, which in turn also works as an indexical sign of masculinity. Beverly Hills and Snoop Dogg, after all, do represent the very elite of the music industry, and what better way to highlight one’s economic/material power than to associate oneself with the elite?

In this manner, the representation of Hosny and his reiteration of the masculine ideals portrayed in the video also work within a cultural reproduction of class society. There is a relation between power and cultural ideals, as pop culture can work to naturalise power relations and making inequality seem normal, or even desirable. The association of Hosny’s material gains – which are shown off in the party thrown in his big LA mansion – with the success in resolving his crisis of masculinity, works to make the strive for a certain high-power social and economic position an essential part of him “being a man.” His position and status is reduced to cultural ideals of manhood rather than politics.

While Si Al Sayed, as a character, originally comes from the so-called Cairo Trilogy by Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz, he is in the music video introduced as a movie character. Furthermore, there are few actual and direct references to the character in the music video, either visual or lyrical. Two things could be interpreted as references; the locking of his partner in her room – Si Al Sayed rarely let his wife leave the house – and the party itself – Si Al Sayed himself indulged in things he taught his family were forbidden, such as music and alcohol. However, the genre of the music video does not lend itself to the same structure as the literary genre, nor the cinematic genre to which the Cairo Trilogy movies.

While Si Al Sayed, as a character, originally comes from the so-called Cairo Trilogy by Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz, he is in the music video introduced as a movie character. Furthermore, there are few actual and direct references to the character in the music video, either visual or lyrical. Two things could be interpreted as references; the locking of his partner in her room – Si Al Sayed rarely let his wife leave the house – and the party itself – Si Al Sayed himself indulged in things he taught his family were forbidden, such as music and alcohol. However, the genre of the music video does not lend itself to the same structure as the literary genre, nor the cinematic genre to which the Cairo Trilogy movies.

Therefore, Si Al Sayed could be seen as nothing more than a trope, a narrative tool that is used simply to drive forward the storyline of Hosny resolving a crisis of masculinity. But, as Si Al Sayed is associated with a certain type of authoritarian, patriarchal family-role, the usage of his character can be seen as a part in a larger process. Hosny associates himself with ideals and expressions considered connected to masculinity, which in turn makes it possible for him to make the claim ‘ana Si Al Sayed,’ meaning ‘I am Si Al Sayed.’ This, then, becomes the penultimate assertion of masculinity, being able to claim the same role as Si Al Sayed. This also means an approval and legitimization of this enactment of masculinity, which relies on the socially powerful position of men, both in public life and, more importantly, in private relationships with women. The result, of course, is a celebration of gender inequality.

Excavating Egyptology

The New York Review of Books has an interesting review of three recent books on the archaeology and filmic versions of ancient Egypt.

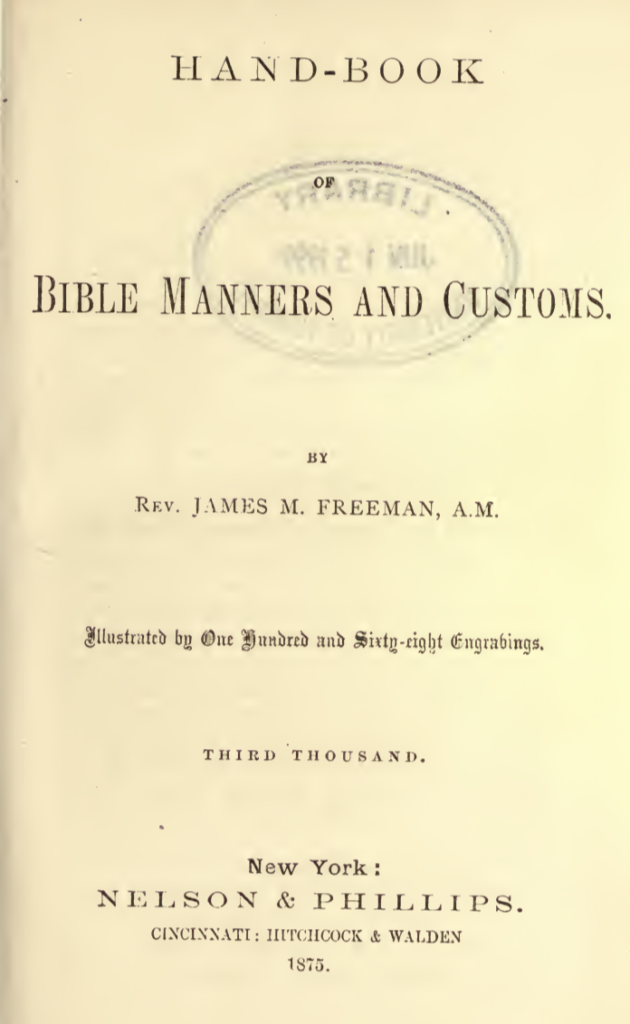

Images from the 19th century “Bible World”

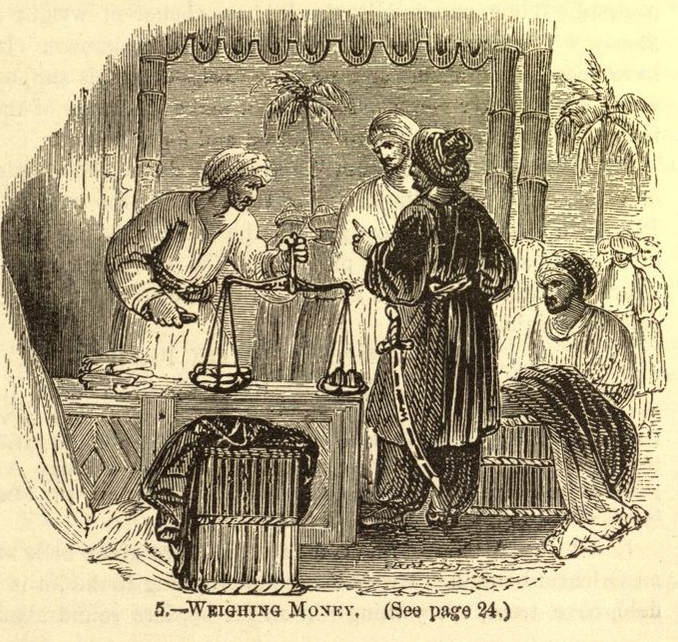

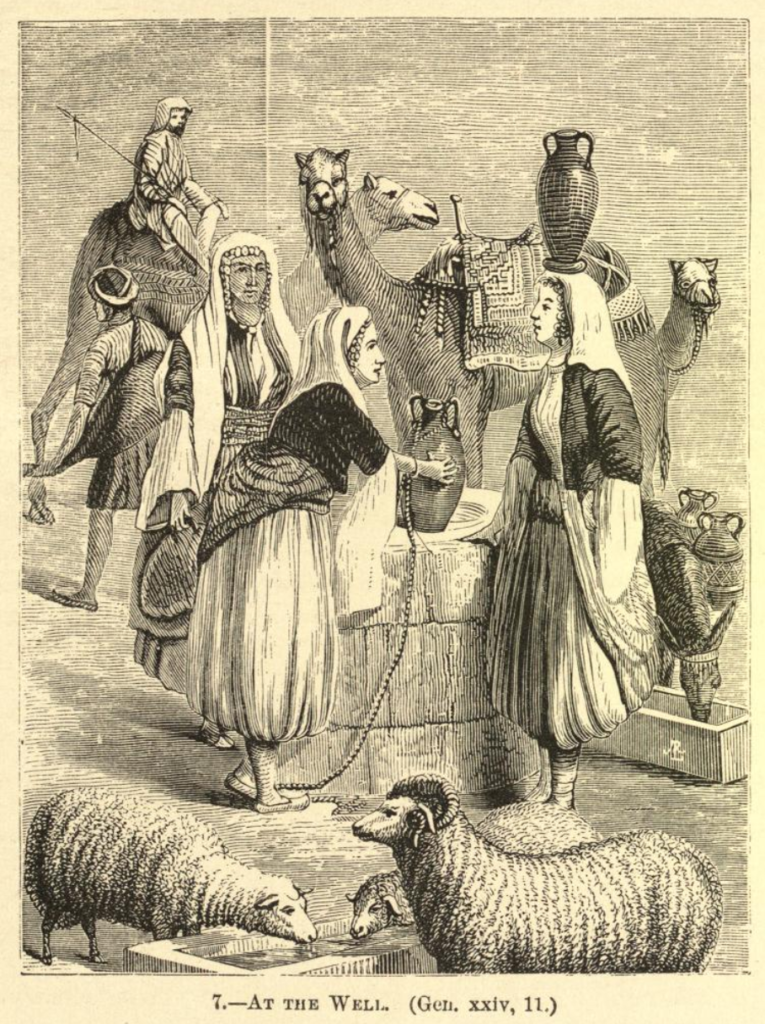

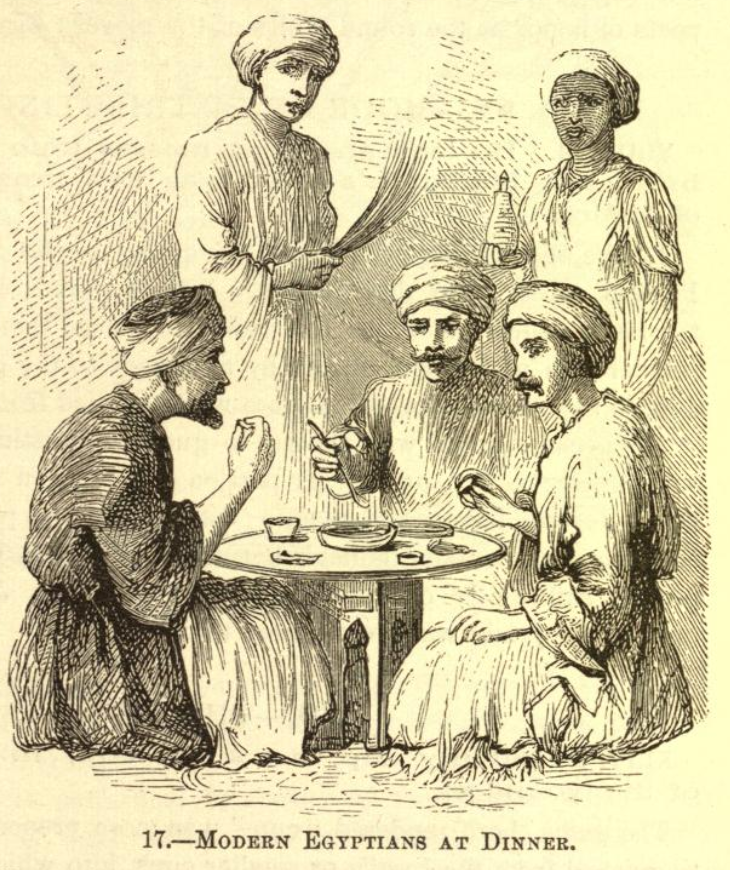

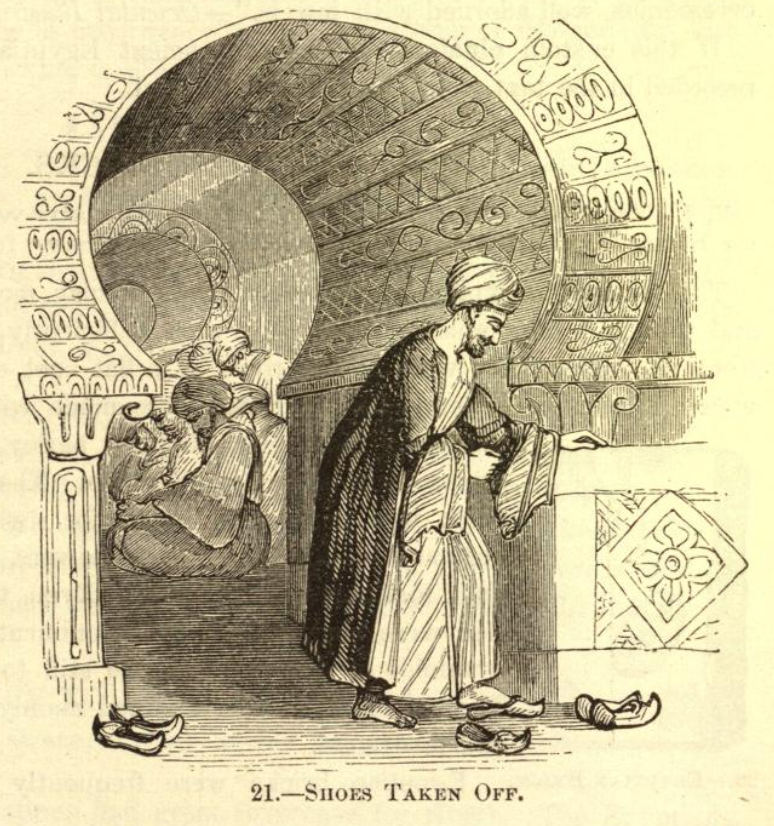

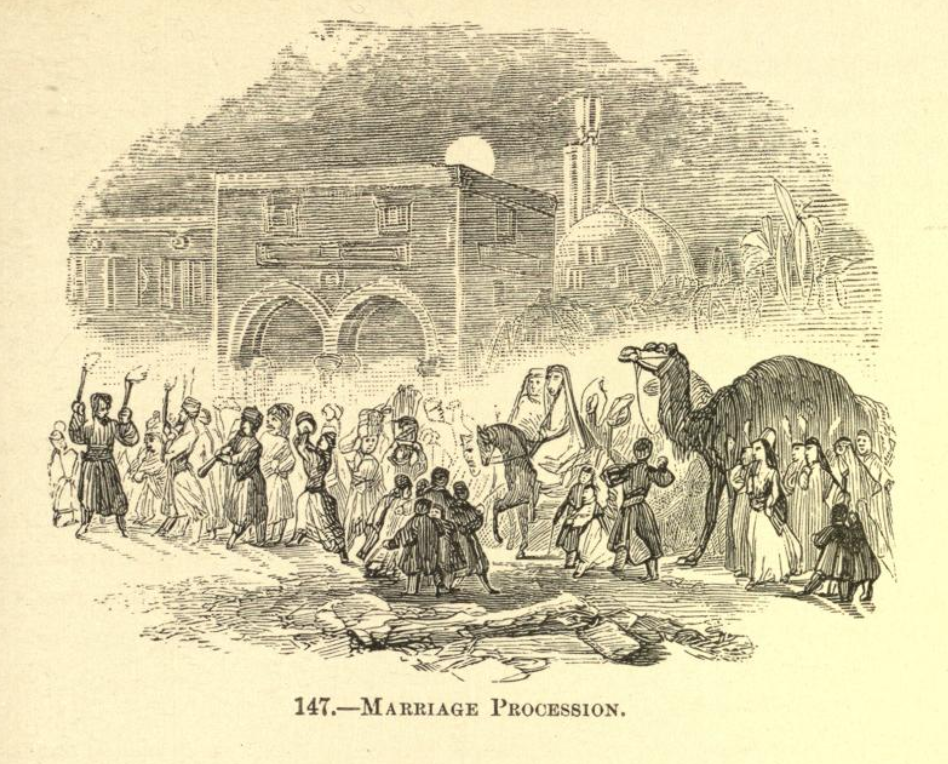

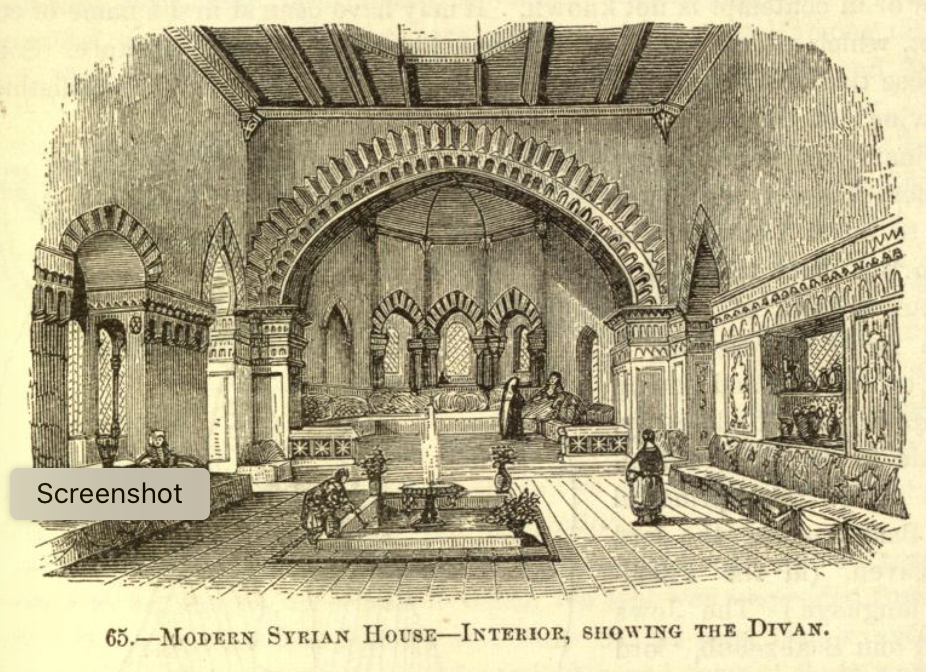

There were many books written by Christian missionaries and clergy during the 19th century. While the text itself has long since been outdated, the engravings are still fascinating to look at. The illustrations here are from an 1875 book of Bible Manners and Customs by the Methodist-Episcopal preacher James M. Freeman. It is available for free on archive.org. But there is also a brand new edition currently in press for 2021 and already noted on Amazon. I attach several of the images below the book title.

Parading with the Pharaohs

Yesterday there was an extravaganza parade in Cairo parading the embalmed remains of 22 ancient Egyptian pharaohs to their new “eternal” resting place in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. You can and should watch the entire show, which you can do here. It featured a major musical composition of Mahleresque length, at times rivaling the soundtrack of Star Wars, but with a lot of drumming to match the pace of the parade. The parade included Egyptian women, shown above, and men dressed in “pharaonic” costume (with a Hollywoodish make-over), men in chariots and coffinesque vehicles carrying the pharaohs and their consorts. On the screen in the auditorium for the elite guests of President el-Sisi, there were scenes of several monuments and dance routines that might best be called an Orient Side Story. You can read all about it here.

The star of the show was the modern day would-be Ramses, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who was front and center before the staged event. He sat like a stoic behind a Covid mask for well over an hour; then as the caravan of his ancestral rulers neared the new museum, there is a scene of several minutes as he walks through the corridors, a smile on his face, to greet the mummies. The reason for spending a large amount of government funds on such a show is obvious: Egypt is desperate to revive the tourism industry. The choreographed show happened at night, with what appear to be few spectators, but the real audience was for those abroad. As one of the speakers said, the heritage of Egypt is the heritage of the entire world.

Presenting Egypt to the world of potential tourists is at the same time sending a message that Egypt is not a dangerous Islamic haven for terrorists, certainly not for the Muslim Brothers after el-Sisi took power. The heritage celebrated in the show was not Islamic, although the theme of ancient Egyptian faith and justice harmonizes with the positive view of Islam the tourism industry must push. The orchestra looked like any classical music orchestra in the world. The close-ups of the players showed most women performers without hijab, as was also the case for the main singers on stage. The only dress visible in the show was what would be seen as modern Western attire, elaborate stage dresses for the singers and supposedly ancient Egyptian costume.

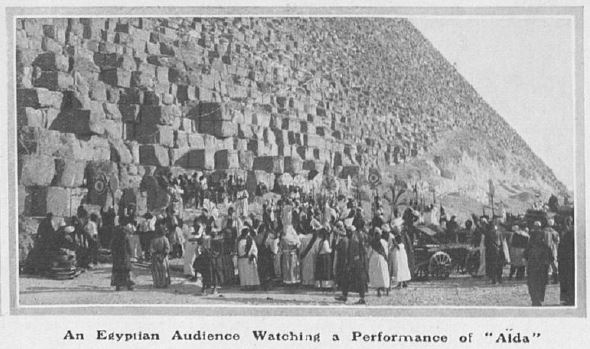

I enjoyed the pomp and pop-cultured kitsch, and the music was enthusiastic in the best way. It was indeed a celebration of Egypt, with an echo of the extravaganza of 1912, when the opera Aida was performed at the foot of the Pyramid of Cheops. I do not know of a recording from that performance, but here is Caruso’s rendition of “Celeste Aida” from 1908. I have no idea how many people watched that performance, but I suspect it was the better-off beys and not the peasant farmers. By the way, Verdi’s Aida was was commissioned by the Khedivial Opera House in Cairo and had its premiere on 24 December 1871.

The idea of the ruler overseeing a parade is a remake of ancient Egyptian rituals, where it was important to renew the divinity of the ruler, a historic note that perhaps made el-Sisi smile in the corridor. After all, wouldn’t all Egyptian peasants have adored their pharaoh, so happy to spend years lugging stone after stone to erect a monstrous resting place for their master? It’s a wonder why the Hebrews didn’t stay and keep making mudbricks instead of almost drowning in the Red Sea and ending up in the desert for 40 years…

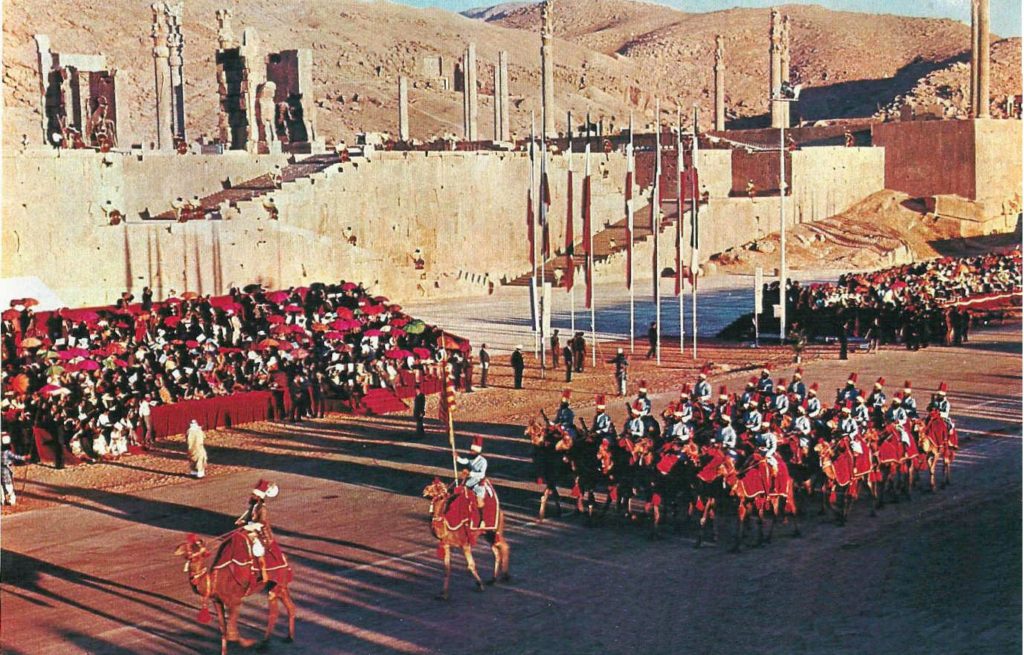

Autocrats, no matter whether they are benevolent or not, love nationalistic parades. In 1971 the Shah of Iran celebrated the founding of the Achaemened by Cyrus the Great 2,500 years earlier. The Soviet Union and China love their military parades and Donald Trump tried to pull one off for Washington DC off when he was in power.

As someone who grew up wanting to be a Biblical Archaeologist and who started a graduate career planning to be a Near Eastern archaeologist, I have long been under the spell of the ancient Egyptians. My visit to the Cheops Pyramid when it was still possible to shimmy up the narrow passage to an empty tomb room and my walk around the ruins of Luxor left memories that continue to this day. If you have not seen these wonders, you should plan to visit Egypt at some point. But Egypt also hosts incredible monuments and historical objects from the Islamic era, especially the early Mamluk period. The entire history of Egypt is worthy of a parade, but only as long as we remember that poverty is still endemic in the country, the ills that led to the Arab Spring have not disappeared, and democracy has taken a back seat.