[Go to the website for an audio interview with Nabil Matar.]

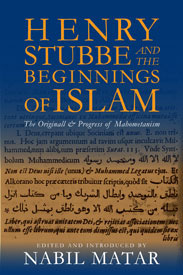

Nabil Matar, Henry Stubbe and the Beginnings of Islam: The Originall & Progress of MahometanismÂ

Columbia University Press, 2014

by Elliott Bazzano, New Books in Islamic Studies, September 18, 2014

In Henry Stubbe and the Beginnings of Islam: The Originall & Progress of Mahometanism (Columbia University Press, 2014), Nabil Matar masterfully edits an important piece of scholarship from seventeenth-century England by scholar and physician, Henry Stubbe (1632-76). Matar also gives a substantial introduction to his annotated edition of Stubbe’s text by situating the author in his historical context. Unlike other early modern writers on Islam, Stubbe’s ostensible goals were not to cast Islam in a negative light. On the contrary, he sought to challenge popular conceptions that understood Islam in negative terms, and although there is no evidence that Stubbe entertained conversion, he admits many admirable characteristics of Islam, ranging from Muhammad’s character to the unity of God. The English polymath was well versed in theological debates of his time and therefore equipped all the more to write the Originall, given the benefit of his comparative framework, which in part explains why the first portion of his text devotes itself to the history of early Christianity. Strikingly, however, it seems that Stubbe never learned Arabic, even though he studied religion with a leading Arabist of his time, Edward Pococke. Indeed, one novelty of Stubbe’s work was precisely his re-evaluation of Latin translations (of primary texts) that were already in circulation. Stubbe’s contributions to scholarship also speak to the history of Orientalism—a word that did not yet exist at Stubbe’s time—or how scholars in the “West†more broadly have approached Islam. Stubbe’s Originall offers insights into present-day Western discourses that still struggle—at times with egregious incompetence—to make sense of Islam and Muslims. In this regard, Matar’s detailed scholarly account of Henry Stubbe and his carefully edited version of the Originall remains as timely as ever. Undoubtedly, this meticulously researched book will interest an array of scholars, including those from disciplines of English literature, History, and Religious Studies.